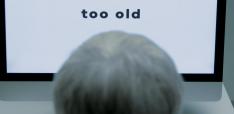

‘Resilience’ and Rituals bring People together, but our True Reactions are more Complex

Charlotte Heath-Kelly explores the complexity of reactions to terrorist attacks.

Seven people were killed in the London Bridge terrorist attack on June 3, seemingly echoing the attack on Westminster in March. Political figures and media commentators have invoked the resilient character of Londoners to terrorism, articulating their stoic refusal to be terrified. Vigils to the victims will be held and spontaneous memorials and tributes will cover the pavements. As we saw after the Manchester bombings, people spontaneously come together to honour the dead, condemn terrorism, and proclaim social unity and resilience “in the face of those who wish to divide us”.

There are patterns in the social responses to these kinds of atrocities. I was in London on the evening of June 3, having just returned from a workshop on the memorialisations that happen after terrorist attacks, during which we talked about the patterns that emerge both in political rhetoric and grassroots actions. We concluded that the complexity and differences of responses to terrorist attacks are routinely underplayed in media coverage and public discussion. “Resilience” and ‘standing together’ appear after terrorist attacks as stylised performances of unity and stoicism.

However, research into post-attack memorialisations can capture the conflict and dissonance of reactions to terrorism. For example, Ana Milosevic has described the conflict at Brussels’ grassroots memorial over which national flags (Israeli or Palestinian?) could be invoked.

Similarly, Sylvain Antichan and Maëlle Bazin spoke at the workshop about the removal of some tributes to the victims of the Paris attacks, and the stylised curation of others at Place de la Republique. The supposed authenticity of the grassroots memorial was actually the result of hours of effort by self-appointed “keepers”. Indeed the self-censorship of racist messages deposited within tributes to victims occurs at all post-terrorist memorials – curators erase and alter texts which do not express an attitude of tolerance and unity. People produce an image of social unity and ‘standing together’ after attacks, when the reality is more complex.

Standing Together

After terrorist attacks, people curate an image of social resilience and togetherness, unprompted by politicians. Talk of “standing together” after terrorist attacks is invoked by both people and politicians. As my colleague Chris Browning has shown, proclamations of social unity and standing together after the Paris attacks served to reestablish a feeling of security. If we stand together and proclaim “Je suis Charlie!” or “Je suis en terrasse!” then we do not feel so vulnerable or alone. We feel fewer death anxieties.

Politicians will embrace notions of Londoners’ “resilience” to terrorism to generate a similar effect. They will tell the public that Londoners (like Mancunians) will stand resilient in the face of terror. And indeed they will. But the complexity of reaction to what happened on Saturday night will be removed from the discussion.

I, and tens of thousands of others, were in the area of the attacks – many travelling home from a concert at the London Stadium. Many of us were prevented from leaving tube stations due to a “security alert” in the area of Bank and London Bridge. Everyone assumed it was another false alarm so gave it little notice.

But later, when thousands of us reached London Euston for trains out of the capital, more of the evening’s events had become clear. People were calm and carried on as usual – but they were also tense, frustrated, packed onto extremely overcrowded trains, and angry. In our carriage, an argument broke out between those standing and those sitting on the floor. Things became heated, and one person was told that their antisocial behaviour was inappropriate “given what has just happened in London tonight”.

So, while Londoners will take on an image of being resilient and unified, it will conceal all the microcosms and complex politics of the event. The immediate reaction to terrorist attacks is overcrowding on the limited services running out of the area, and – given that London experienced a night attack – the consumption of alcohol impacted the amount of resilience and unity shown by those on public transport.

The trope of “standing resilient against terror” produces a more comforting image of social unity and togetherness. But research shows the awkward details of social responses to terrorism. In the case of night attacks, inebriated revellers and travellers on the public transport system will demand access to trains that don’t exist, react badly to overcrowding, but also demonstrate incredible patience in the face of provocation by others. Some of this behaviour fits the image of unity and tolerance after terrorism, but some doesn’t.

So when British resilience to terrorist attacks is (once again) invoked by politicians, we will see the rituals that support social unity and which comfort us. But, underneath them, reactions to terrorism are more complex. We will portray ourselves as resilient, because that’s what we want to be.

Charlotte Heath-Kelly is Associate Professor of Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick. This post first appeared on The Conversation.

Photo credit: Boursier Art Photography via Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA