Extremism and Ethnicity Part III - A Viable Model For Practical Solutions: South Tyrol

In the third part of this six part series, Roland Benedikter proposes a model of regional autonomy to institutionalize minority rights in ethnic conflict areas.

In order to defeat ISIS, ethnic differences in Iraq (and beyond) must be mirrored by concrete, practical and legally binding institutional arrangements able to integrate minorities and majorities into a sound overall framework structured and guaranteed by law. That will be the best way to keep the remnants of ISIS—including their ideological traces—at bay after a probable victory over the extremists’ army. The best practical solution to implementing such an arrangement is the South Tyrol model of local and regional autonomy. It consists in a complexity adequate to, and a non-discriminatory territorial autonomization of, ethnically problematic areas and it is dedicated to the protection and recognition of ethnic minorities and ethnic and religious particularities through legal guarantees. As far as can be seen now, this may be the only institutional model that will work in the long-term because it is based on legal and institutional regulations, not only on political diplomacy or treaties about national representation of minorities in the parliament or government alone. So what is the South Tyrol model about in detail? And how, concretely, can it help to defeat ISIS in a sustainable way?

First of all, some prerequisites need to be considered. Any win-win arrangement would have to balance political, cultural and ethnic dimensions while taking into account the extraordinary power of contextual political factors in multiethnic and minority areas; these factors include traditions, customs, worldviews, religion, historic identity, mythology and social psychology. This means that it must consider factors outside institutional and party politics, while at the same time respecting both the (sometimes very specific) interests of tribal politics and of an Iraqi nation in need of unity and stability. This in turn implies the need to reconcile “classical” party and institutional politics with the emerging field of contextual politics – which describes one of the potentially most important challenges of contemporary politics on a global scale.

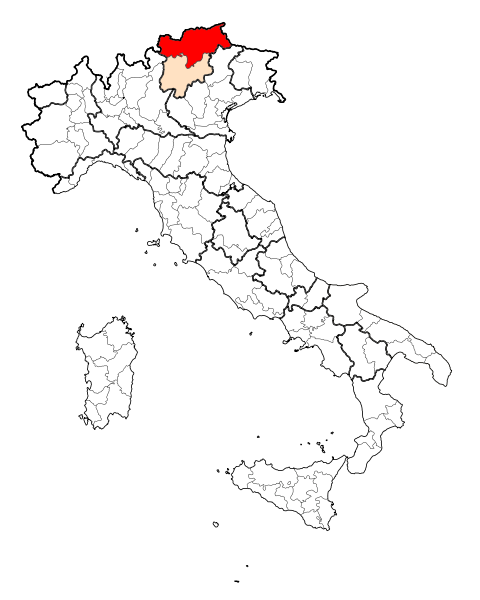

Perhaps the most viable interdisciplinary model of pacification and justice for all sides involved, at least as a transitional solution, could be one that strictly adheres to realpolitik: a non-ideological, practical, and problem-oriented policy applied to concrete circumstances on the ground. This solution might follow the example of northern Italy’s trilingual Autonomous Province of Bolzano-South Tyrol, a region where three different ethnic groups coexist in harmony and that is overseen and protected by the European Union. A similar solution, inspired by the South Tyrol example, could be implemented immediately after the military victory over ISIS in certain Sunni areas, as well as in ethnically mixed areas like Mosul or Kirkuk. It would establish regional autonomy for selected tribal and ethnic areas within the national borders of Iraq – self-administration (with elements of self-determination) without separation.

The regional autonomy model of South Tyrol, established in the framework of a “second autonomy statute” in 1972 and today proven successful for more than 40 years, is a model of “inter-ethnic tolerance established by law.“ To many, it is the so far best example for the handling of ethnic divisions found in Europe, and in the world.

South Tyrol is a small area approximately half the size of the Kirkuk area along the mountainous alpine border between Italy, Austria and Switzerland. With a total population of 505,000, it has a high degree of political and cultural autonomy and its model presents a working and practical solution to multi-ethnic co-existence. Here, the German speakers are the majority (67%) and have the majority in the provincial parliament, which disposes of an autonomous legislative and executive power. Italian state population in the province amounts to 26%, and a third ethnic group, the Rhaeto-Romanic Ladins, represent 4%.

Before World War I the region of South Tyrol was part of Austria. A majority (95%) of the area’s inhabitants were culturally Austrian, and thus German native speakers. Ceded to Italy by the Treaty of St. Germain in 1919 against the will of the population, South Tyrol experienced a troubled and difficult transition to its current status of a wide-ranging linguistic and cultural autonomy. Not until June 1992 did the foreign ministers of Austria and Italy sign what was to be a satisfying agreement safeguarding South Tyrol’s full autonomous status within the Republic of Italy.

Three years following the annexation in 1919, Mussolini´s Fascist government began the forced Italianization the region by attracting large numbers of Italians, mainly from the South, to settle in the area (similar to the policy adopted by the Chinese in today’s Tibet). This practice was interrupted only by World War II. After the end of the Second World War South Tyrolese representatives and the provisional government of Austria began working to see that South Tyrol would be returned to Austria. The Great Powers of the victorious Allies had, however, already rejected such claims in the autumn of 1945 and, despite further massive attempts by the South Tyrolese and Austria (in South Tyrol more than 80% of the native population signed the call for a plebiscite, and in the capital of the Austrian federal state of Tyrol, lnnsbruck, a huge demonstration was held on 5 May 1946), a final negative decision was taken at the end of April 1946. The only way left open now for Austria and ltaly was to negotiate directly so that South Tyrol would obtain an “intermediate” status through some form of self-government. Special provisions and legislation needed to grant German-speaking citizens equalization of the German and Italian languages in public offices and official documents, as well as before the courts. A basic agreement was reached within the framework of the peace negotiations in Paris. On September 5, 1946 the “Paris Agreement” was signed by the foreign ministers of ltaly and Austria, Alcide Degasperi and Karl Gruber, and annexed to the peace treaty with ltaly, thus giving the South Tyrol question official international standing.

In the following years, Italy did not fulfill its obligations as stipulation at the Paris Agreement and therefore, in September 1959, the South Tyrol question was raised at the United Nations by the then Austrian Foreign Minister Bruno Kreisky. Further efforts by the SVP (the South Tyrolean Peoples Party, an ethnic unification party representing the Austrian and Ladin population) and Austria were not successful: in 1961 bombing attacks were carried out by members of the growing independence movement with 37 separate incidents in the night of June 11 alone. They were followed by new negotiations with Rome, which reached a successful conclusion. Little by little a whole package of measures to put the self-government of the South Tyrol area into effect was agreed upon. It was approved by a narrow majority of the SVP at its congress on 23 November, 1969 against its independentist wing, and thereafter by the ltalian and Austrian governments. Only after the coming into effect of the new Autonomy Statute in 1972 was the equalization of the minorities energetically pursued with special executive measures and decrees by the Italian state.

As noted above, three ethnic groups currently live in South Tyrol: the German and Ladin speaking minorities and the Italian state population. According to the census carried out on October 9, 2011, the German-speaking ethnic group with 314,604 people represent 67.15 per cent of the population; the Italians with 118,120 represent 26.06 per cent and the Ladins with 20,548 4.53 per cent. The Ladins are the oldest and at the same time the smallest language group in the province. They had already been resident in the country at the time of the Roman conquest from the South, but were then increasingly pushed back by the German tribes invading from the North. The Italians in South Tyrol mainly live in the cities of Bolzano/Bozen/Bulzan (carrying three names according to the three ethnicities) and Merano/Meran/Maran and in the bigger centers. At the time of the 1910 census, the last to be held before World War I and therefore before South Tyrol's annexation by Italy, there were only 17,339 Italian-speaking inhabitants in South Tyrol (2.9 per cent of the population). The considerable increase of the Italian population of South Tyrol occurred in the 1930s as a consequence of the violent Fascist Italianization of the province, but it continued in the years after 1945, reaching its peak (34.3 per cent), at the 1961 census. Since then, the Italian percentage of the population has been in decline (1971: 33.3 per cent; 1981: 28.7 per cent, 1991: 27.65 per cent, 2001: 26.47 per cent).

What are the pillars of South Tyrolean autonomy today?

Until today, the statute of 1972 represents a solid guarantee that the German and Ladin linguistic minorities (at the national level) can survive as ethnic groups with their own linguistic and cultural identities, so that the implementation and observation of the measures of protection form the basis for a peaceful co-existence of the three ethnic and linguistic groups in the province. Currently, the pillars of the South Tyrolean autonomy are:

• 90% of the taxes collected in the province by the Italian national authorities—South Tyrol has no independent tax authority—are automatically restituted to the local autonomous government. They are then distributed proportionally to the three ethnic groups, thus in theory benefitting every citizen of South Tyrol equally, without favoring either the Italian state population nor the minorities. That’s why the South Tyrolean autonomy is explicitly considered a territorial autonomy, not an ethnic autonomy, which would disadvantage the Italian state population living on the territory.

• The so-called Ethnic Proportions Decree demands the declaration of ethnic affiliation by every citizen on the soil of South Tyrol in the framework of every census, as well as the proof of an acceptable knowledge of the major provincial languages in South Tyrol, German and Italian, as obligatory for people employed in the public sector. The “acceptable knowledge of the German and Italian languages” is usually ascertained through a bilingualism examination, which can also be extended to trilingualism. This exam is a hurdle for all candidates of the Italian national state who have no knowledge of German and therefore it prevents uncontrolled immigration and is implicitly an advantage for the local population in search of labor. In the competition for employment in the public sector, the vast majority of the candidates from other Italian provinces would be excluded—to the advantage and benefit of South Tyrolean residents. This can be seen as one major reason for high employment in the province (currently 4,5% unemployment rate), which is another main precondition for the success of the autonomy model and for the peaceful co-existence between the ethnic groups. Most probably, the autonomy regulation wouldn’t be accepted so well by all three ethnic groups without the apparent economic success and the practical benefits for all local citizens.

• The proportion of percentages between the ethnic groups also regulates the distribution of public money to the respective groups, as well as the composition of public bodies and the distribution of administrative and bureaucratic posts in the public administration. In theory, every group has the right to a ratio of posts in public administration matching its percentage in the census; at present, this means that 67% of the posts are announced for declared members of the ethnic German (Austrian) speaking group, 26% for the Italians, and 4% for the Ladins. Nevertheless, the measure is handled flexibly, i.e. when for example no appropriate candidate can be found for a job reserved for the German speaking group, it is opened up to all groups.

• The regulations on bi- and trilingualism contained in the above-mentioned Ethnic Proportions Decree have been extended to the recruitment of personnel in firms, societies and bodies which carry out public services or services of use to the public in the Autonomous Province of Bozen (Bolzano).

• In order to ensure the independent cultural development of each

linguistic group, each has its own administrative and organizational domain in form of an independent local ministry for culture and schooling. The Italian ethnic group culturally cooperates closely with other Italian provinces and regions, while the German and Ladin ethnic groups maintain active contacts with the extra-territorial German and Ladin (Raeto-Romance) cultural worlds. According to the autonomy statute, the province of South Tyrol has primary legislative powers in terms of culture.

• Legal proceedings and trials must be conducted in the declared mother tongue of the accused.

In such an overall arrangement, the measures to protect the minorities are of particular relevance. The autonomy statute of 1972, the so-called “Autonomy Package,“ consisted of 137 measures. The measures should have been issued within four years of signature by the Italian national government. But in the end more than 20 years were required for the constantly changing Italian governments to finally implement it. On the basis of the Paris Agreement, the South Tyrol autonomy statute should ensure the maintenance and linguistic and cultural development of the German and Ladin linguistic groups within the framework of the ltalian national state. But at the same time the benefits of the enlarged powers of self-government apply to members of all three linguistic groups in South Tyrol.

• The most important primary powers of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol are: place naming, protection of objects of artistic and ethnic value, the regulation of small holdings, arts and crafts, local customs and traditions, planning and building, public housing, public construction, common rights (for pasturage and timber), mining, hunting and fishing, agriculture and forestry, the protection of fauna and flora, fairs and markets, prevention of disasters, transport, tourism, expropriation, public welfare, nursery schools, school welfare, and vocational training.

• Restricted powers apply to teaching in primary and secondary schools, trade and commerce, apprenticeships, promotion of industrial production, hygiene and health, sport and leisure.

In addition, census and linguistic proportions play a crucial role in making to model work. This is because an important prerequisite for the protection of an ethnic minority is to know its exact numerical size. In the 1920s and 1930s the Italian Fascists succeeded almost completely in forcing the South Tyroleans (“those of foreign origin,” as Mussolini described them in his speech to the Parliament in Rome in 1928) out of public employment and regional administration.

Furthermore, during the Fascist dictatorship, public housing in South Tyrol was almost exclusively allotted to Italian-speaking tenants. This kind of policy continued even after the 1946 “Paris Agreement” which provided for “equality of rights as regards the entering upon public offices with a view to reaching a more appropriate proportion of employment between the two ethnical groups.” From 1935 to 1943 3,100 units of public housing were built in South Tyrol (of which 2,800 were in the capital Bolzano/Bozen/Bulzan), which were entirely allotted to immigrating Italian families (not unlike today’s practice with regard to Chinese immigrants in Tibet). From 1950 to 1959 the national government built a further 5,500 units, of which 3,500 were in Bolzano/Bozen/Bulzan with only 5 per cent given to local German-speaking tenants.

The introduction of a fair distribution of administrative posts and housing according to the numerical strength of the three ethnic groups was therefore perceived as reparation of Fascist injustice by the minorities. Since 1972, the key to that distribution has been the above-mentioned principle of ethnic proportions which is based on the numerical strength of the three linguistic groups living in the province according to the latest census. Public housing built since 1972 was distributed according to ethnic proportions; but since 1988 it has been distributed according to a so-called “combined proportion” which takes into account not only the numerical strength of the three linguistic groups but also the needs of each group based on the requests for housing submitted.

Concerning the local bodies in the province (personnel of the public sector, the municipalities, the health services, etc.), the equality of rights which regulates the entering upon public offices provided for in the Paris Agreement was gradually implemented. By the year 2002, employment in Italian national and semi-autonomous bodies in South Tyrol (railways, postal service, roads administration, customs service, court administration) also occurred proportionally according to the strength of the three ethnic groups. However, certain state bodies such as, for example, the military, the police, and the security service are not subject to the principle of ethnic proportions.

To be continued…

Roland Benedikter is Research Scholar at the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies of the University of California at Santa Barbara. The author thanks Victor Faessel, Phd, Program Director of the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies of the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB), for advising on this text. Read part II here.