Does income inequality increase economic and financial instability?

As countries struggle to reduce their fiscal deficits, some governments, most notably the U.K.’s, are turning to large budget cuts. Recent research shows that fiscal policy can also play a key role in stabilizing G20 countries’ economies and financial systems by reducing risk-taking behaviour and systemic risk.

To begin with, it is important to note that there is strong reason to believe that tax rates on top incomes can be increased substantially without hurting economic growth. Depending on your ideological beliefs, reducing inequality is desirable in itself. Taking a closer look at the impact of increasing income inequality in the United States over the past century, it seems that reduced income inequality could also reduce the risk of financial crises.

To understand why tax rates are below their optimal level, it is useful to look at the Laffer curve, named after the economist Arthur Laffer. The idea behind the Laffer curve is that tax rates can be set at an optimum level: if the rate is zero, no revenues will be raised; if it is 100%, no one will be willing to work to earn money, as they will expect any money they make to be taxed away. Emmanuel Saez, an economist at UC Berkeley and the 2009 recipient of the Clark medal, has estimated that a rate between 60% and 80% for top incomes would be optimal.

A recent survey of American economists’ positions on the Laffer curve suggests that top marginal tax rates can be increased significantly in the U.S.

But perhaps more importantly, reducing income inequality through increased top tax rates could significantly reduce systemic risk by modifying incentives for risk taking by top income earners. Why? A comparison of the crises of 1929 and 2008 in the United States paints a striking picture of the rise in inequality that preceded both crises and suggests that there may be a powerful link between sharp increases in income inequality and the risk of severe economic crisis.

The two twenty-year periods that preceded the crises of 1929 and 2008, respectively, were characterized in the United States by a near doubling of the share of income going to the top 1% of the income distribution. In both 1928 and 2007, this share reached nearly a quarter of national income. This surge in top incomes was accompanied by a sharp increase in household debt.

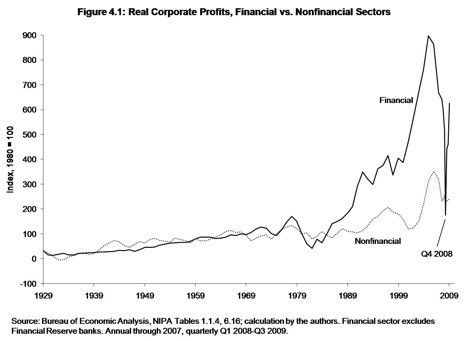

Mainstream economics implies that in the face of increasing inequalities since the 1980s, households at the lower end of the income distribution should have sought to reduce their consumption rather than increase their debt. Conversely, it implies that the rate of return on the the savings of economic elites should have progressively declined. What actually happened is the exact opposite. The bottom of the income distribution got massively indebted via a variety of means, (home equity and increasing interest rate loans, various types of credit cards, etc). Meanwhile, excess corporate profits in the financial sector (relative to corporate non-financial economy, adjusted for inflation) fueled a sustained increase in the income of the top 1% of the income distribution’s income (see charts).

In the 1990s, lower-income households and the financial sector partook in the takeoff of the housing bubble. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were created, under the Democratic Party’s leadership, to allow more households to have access to home ownership through looser credit. This increased the (subprime) demand for loans. Banks, on the other hand, were eager to find high-yield investments, and saw the ongoing housing bubble as a welcome successor to dot com stock after the internet bubble crashed in 2001. The dominant view that we were living in an era of “Great Moderation,” characterized by sound monetary policy and low rates of inflation, went unchallenged (Ben Bernanke was one of its most articulate proponents), and contributed to the idea that the increase in housing prices reflected macroeconomic fundamentals and would continue in the foreseeable future.

It is worth noting here that median income has stagnated in the US over the past three decades, and it actually declined between 2000 and 2006. This suggests that access to housing may have helped households “overconsume” – that is, consume beyond what income alone would have permitted, using debt. Additionally, many households were lured by the fact that many home loans required no savings. So while predatory lending clearly played a major role in increasing the supply of subprime loans, the prospect, no matter how illusory, of escaping one’s economic condition through ownership made possible by subprime loans no doubt also fuelled the demand for subprime loans. As a result, home ownership as a share of population increased. It increased most notably in the bottom fifth of the income distribution, as well as for some minorities. The punch, of course, is that rising house prices all over the country allowed all these recent home owners to consume well beyond their actual means – that is, their income.

While the housing bubble and the financialization of the economy that accompanied it allowed lower-income households to consume more than they otherwise could have, the top of the income distribution profited directly, and disproportionately more, from the explosion of the subprime market. Financial innovation, which stemmed in close tandem with the housing bubble, gave a major boost to financial sector profits relative to profits in the rest of the economy (see chart). Financial elites benefited from sharp income gains and increases in their net wealth via a combination of outsized bonuses, dividends and stock appreciation.

To sum up, the systemic house of cards that was built looked as follows. On the one hand, the lower and middle classes became strikingly overindebted. On the other hand, the richest Americans saw their wages and wealth rise sharply. A bloated – and growing – financial system (both as a share of GDP and in terms of its influence on policy makers in Washington) played the role of bridging the gap between these two segments of society, which were drifting apart in many respects. How viable was the system? When the bubble burst, debtors defaulted in swaths, casting away both their houses and the American dream, and financial returns plummeted. The key source of this system’s fragility, arguably, was the fact that economic growth was based not on productivity gains in the real economy but on a combination of debt-fuelled consumption and financialization of the economy.

What should we learn from this crisis? The key takeaway is that the distribution of income matters for the health of the economy. Increased redistribution, increased top marginal and capital gains taxes, could well help moderate the size of the incomes at the very top (which are concentrated in the financial sector). Wide-ranging financial education programs could help low-income earners avoid over indebtedness.

Rapidly rising income inequality heightens systemic risk through financial leveraging by poor and middle-income households as well as excessive risk taking (in the pursuit of high rates of return) by financial elites. Current proponents of increased regulation of the international financial system, as well as policy makers in the G20, would do well to add income inequality to the list of potential threats to financial instability.