Reshaping World Trade: The Export Finance of the Emerging Economies

Kristen Hopewell is the author of the third commentary in the Emerging Global Governance (EGG) series. It argues that export credit is proving to be a useful lens on both the challenges of multilateral cooperation amid contemporary power shifts, as well as the diminishing capacity of the US.

The world of global trade is being remade, perhaps under our noses. Much of the scholarly and policy attention over the last decade has been focused on the paralysis in the global trading regime, the World Trade Organization (WTO). Others have focused on the rise of regional free trade agreements (FTAs), and then nascent mega FTA proposals. However, at a deeper, and arguably more profound level, important changes in the world of trade have been underway throughout the last decade.

Export finance is a critical aspect of global trade, and one that is being profoundly affected by growing multipolarity: the rise of the “BRICs” (Brazil, Russia, India and China), and the corresponding decline in the political and economic dominance of the US, and the Global North more broadly.

Approximately 80-90% of world trade relies on some form of financing, with over $10 trillion in trade finance provided every year. Although the majority of trade finance is provided by the private sector, states also play a vital role in financing trade. Every major economy has an export credit agency (ECA) that provides various forms of financing to facilitate and increase exports, including direct loans to foreign buyers, insurance and loan guarantees, working capital financing, and finance for large-scale infrastructure and industrial projects.

For many countries, government-supported export credit is a core part of their industrial policy and national export strategies, and its importance has only been amplified since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. During the crisis, when the availability of commercial credit contracted dramatically, official export credit played a critical role in filling the gap in trade finance, keeping international trade moving and preventing the financial crisis from spiralling into a world-wide depression. The ensuing implementation of new Basel III financial regulations diminished the availability of private lending for certain forms of trade, increasing the need for state-backed export credit. And, since the crisis, many states have increasingly come to view export credit as a key instrument to foster domestic economic growth by boosting exports.

Since the 1970s, the use of state-backed export credit has been governed by a set of rules established at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an international institution composed primarily of advanced-industrialized states (and therefore known as a “rich man’s club”). The US led the creation of these rules – which limit the ability of states to use export credit to subsidize, and thus artificially boost, their exports – and they have become progressively tighter and more restrictive through ongoing negotiation over the ensuing decades. Until recently, the OECD Arrangement on Export Credits was considered a highly effective example of multilateral cooperation being used to prevent an upward spiral of competitive subsidization among states, which would drain national budgets and reduce aggregate welfare.

Emerging Actors, New Trends

Recently, however, there has been a dramatic rise in unregulated financing, driven by a massive increase in export credit provided by the emerging economies, who are not members of the OECD and therefore not bound by its rules. In addition, many OECD members are increasingly providing forms of support not regulated by the Arrangement. While virtually all trade-related finance fell under the disciplines of the OECD Arrangement in 1999, it is estimated that the majority of trade finance provided by states today (65%) falls beyond the scope of OECD rules. We are thus witnessing an erosion in the efficacy of the OECD disciplines and increasing inter-state competition via export credit. Ironically, the one state moving in the opposite direction is the US, where a campaign by the ultra-free-market Tea Party movement has severely constrained its provision of export credit, thereby undermining the competitiveness of key US industrial sectors.

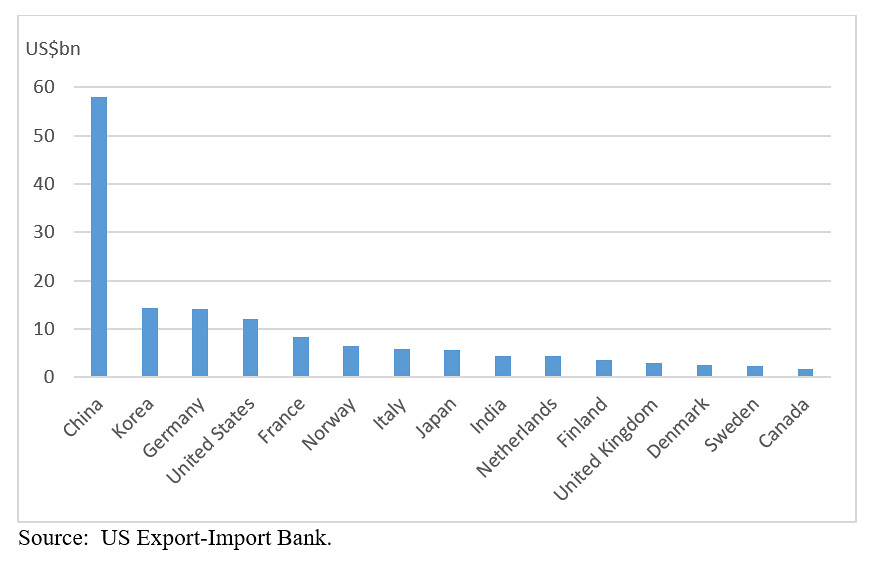

In recent decades, the global landscape of state-backed export credit has changed dramatically due to a surge in export credit provision by the BRICs. Between 2000 and 2014, the BRICs increased their official export financing from less than 3% to 40% of the world total. The vast majority of this increase has come from China, who is now the world’s largest export credit provider. In 2014, China supplied $58 billion in export credit support – far more than the $12 billion provided by the US and, indeed, more than all the G7 rich countries combined – plus an additional $43 billion in overseas investment financing to promote its exports (Figure 1).

Figure 1: New Medium- and Long-Term Official Export Credit Volumes, 2014

Government-supported export credit has been an important driver of China’s export growth. It is one of the prime means by which China deploys its newfound financial power to give its firms a competitive advantage in global markets, while fostering industrial upgrading and the development of strategic sectors. Export credit has been a central factor in the much-reported expansion of China’s activities in Africa, Latin America and elsewhere. While often mistakenly described as aid, most of China’s lending to Africa and other parts of the developing world is in fact export credit – loans tied to the export of Chinese goods.

China’s leadership of new international financial institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the BRICS’ New Development Bank, and its considerable investment in the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative (the “New Silk Road”), will provide further avenues for its use of export credit to support its industries and the “going out” of Chinese enterprises abroad.

Although smaller in scale, the other emerging economies are also using export financing strategically in key sectors to significant effect – including Brazil in construction, Russia in nuclear energy, and India in transportation and energy. The dramatic expansion in the use of official export credit by the BRICs poses a competitive threat to the established powers, and it has significant implications for global economic governance.

The Global Challenge

Despite prodding from the US and other advanced-industrialized states, China and the other BRICs refused to join the OECD Arrangement, a set of rules that they played no role in creating. In 2012, the US drove the creation of a new International Working Group on Export Credits (IWG), involving 18 major developed and developing countries, intended to negotiate a successor to the OECD Arrangement that would incorporate China and the other major emerging economies. However, given the importance of export credit as an export promotion and development tool, the BRICs have little incentive either to join existing governance arrangements or to subject themselves to new disciplines. As a result, not surprisingly, there has been little progress in the IWG.

Export credit is thus proving to be a useful lens on emerging trends in world trade and trade finance that are reshaping the world economy. It highlights both the challenges of multilateral cooperation amid contemporary power shifts, as well as the diminishing capacity of the US hegemon to steer global rule-making in a context of growing multipolarity.

Kristen Hopewell is Senior Lecturer in International Political Economy at the University of Edinburgh. Her current research program on the changing global dynamics of export credit is supported by an ESRC Future Research Leaders grant. Dr. Hopewell is the author of the recently published book, Breaking the WTO: How Emerging Powers Disrupted the Neoliberal Project (Stanford University Press, 2016). Prior to joining the academy, Kristen Hopewell was a trade official of the Government of Canada, and an investment banker at Morgan Stanley.

Photo credit: philHendley via Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND