The social cost of the sustainable transition

Markus H.-P. Müller reminds us why we need to think hard and find the best ways to tackle the consequences and risks of climate change.

With our climate system apparently changing at an ever-increasing pace, some countries are moving ahead quickly with measures to encourage economies to transition to more sustainable economic models. Societies are assessing both the best path to more sustainable economies (the transition) and what these changed economies will look like (the transformation). But, here and elsewhere, politicians and social movements are pushing back, notably around transportation and domestic heating charging and restrictions. Debate at the COP28 in November/December 2023 also highlighted the enormous challenges the transition means for everyone – the community, corporations and governments. As ever, discussions revolve around the transformation costs of policies. But how exactly should such costs be measured?

Calculating costs vs. benefits: how broad do you go?

Usually, costs give a monetary measure of how much one must give to get a certain product or service. However, in the case of tackling climate change, the definition of “costs” may need to be broadened out to include more aspects than the traditional definition. And, while climate change is the most immediate challenge, there will also be major future (largely uncalculated) costs in tackling other environmental issues too.

According to a 2023 assessment we have already transgressed six of the nine “planetary boundaries” (biogeochemical flows, freshwater change, land system change, biosphere integrity, climate change and novel entities), putting humanity outside its safe operating space. Approaching the problem from a different direction, a separate UN assessment of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), published in October 2023, shows substantial shortfalls in progress towards many SDGs, implying much more spending to come.

Let us focus first on climate policies. What is their function? Ultimately, they are aimed at incentivizing (or simply instructing) economic agents, such as companies and private households, to change their behaviour or adjust production processes to more climate-friendly methods.

As climate scientists have become more and more able to describe possible climate change scenarios – and their consequences – societies and policymakers realize the scale of adjustment that is needed. But for policymakers, there remains an obvious balancing act between the costs of climate measures and the burden placed on the societies they serve.

Social costs of carbon: very useful but imperfect

Quantifying this cost/benefit balance can be done in various ways. One approach is via calculating the social costs of carbon (SCC) – a measure of the damages that the emission of an additional ton of carbon causes society. The higher the SCC is, the more incentive there is to avoid further emissions.

SCC originates from a desire to include climate sciences in macroeconomic modelling. So-called Integrated Assessment Models, for which Bill Nordhaus received the Nobel Prize in 2018, should enable researchers and policymakers to work out whether benefits that follow from emissions reduction are economically efficient, in the sense that they are larger than the costs these measures cause.

But does SCC provide a true measure of cost? There are, essentially, two sets of problems here. First, SCC calculations need to be based on credible forecasts of C02 and other emissions under future climate paths and their implications. We also need to assess degrees of uncertainty around these forecasts. Recent work has therefore attempted to upgrade the methodology of previous forecasts. But any SCC calculation then also faces the equally-difficult challenge of capturing all the economic costs and benefits of avoiding carbon emissions as part of pathways to meet agreed environmental targets. This is challenging because it’s very hard to quantify (for example) the implications of labour market disruption from necessary industry restructuring, any related increase in the cost of living, or possible threats to personal freedom from climate change (or policies intended to ameliorate it). Additionally, the output of SCC models varies greatly dependent on other inputs, e.g. the discount rate applied, which is also difficult to assess properly.

Chosen transition paths may also be interrupted, or difficult to complete (one current concern, for example, relates to shortfalls of raw materials needed for the energy transition), also complicating calculations of SCC. We need to find ways of including such issues around cost-benefit analyses of climate policies – as they may ultimately involve issues more fundamental for society than pure economic considerations.

This will involve clear distinctions between costs and benefits in general, as these can often get muddled up. Consider transport, for example. Transportation restrictions for environmental reasons may involve limiting personal mobility (a cost) but could also result in improved air quality and thus health (a benefit). Another example is provided by the process industries (turning raw materials into end-products or commodities): here, moving to more regenerative models may increase the cost of final output, but should also deliver a wide range of short and long-term benefits. Openly discussing such complexities is necessary in open societies to underpin broad public support for policy.

Market vs. command-driven policy: unexpected side-effects

What sort of toolbox do policy makers need to do this? As ever in economics, there are advocates of approaches across a wide spectrum from relying on the free-market to the command-driven. I do believe that social market economy tools – somewhere in the middle of this spectrum – can and should play an important role here.

Recently, the trend appears to have been away from using market-based tools such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems (i.e. putting a market value on emissions) in favour of a very granular and more prescriptive regulation about what is to be encouraged or discouraged.

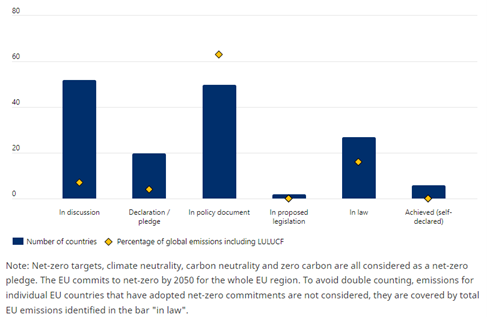

Figure 1: Number of countries with a net-zero pledge and % share in global emissions

Source: OECD (2023), IPAC Dashboard

But the result, seemingly perversely, of a more granular and prescriptive approach seems to be more uncertainty. This is because while it may be tempting to take a centralized approach to designing future economic transformation, this approach does have a fundamental flaw. It assumes that policy makers can understand and predict the future – in the sense that they know in advance which technologies will turn out to be most efficient and which policies will be most effective. Understanding and predicting the future has always been difficult, and the uncertainties around environmental transformation make it even more so.

This centrally-driven prescriptive approach has another disadvantage – whenever new information is received which is not in line with policymakers’ expectations, then regulation needs to change to maintain an optimum course. The prospect of frequent changes in policy direction increases uncertainty for households and businesses. (In addition, a prescriptive approach may also be more vulnerable to short-term changes based on political expediency as seen recently.)

As economic transformation requires long-term investments on large scale, investors need a degree confidence and certainty about the guidelines in which they are operating. The risk is that a centrally-driven prescriptive approach delivers the exact opposite.

So, I would argue that we need to swing back along the spectrum of policy options, towards more market-based tools, but in a social market context. The challenge, then, is to design these tools so they are sufficiently strict to ensure progress on environmental targets – but give leeway to companies that find the most efficient way to make environmental improvements based on operational and economic considerations. Such tools also need to consider the specific challenges faced by many countries in the Global South. Do individuals or firms here need different incentives to meet different needs? While the recent COP28 pledges to the loss and damage fund for the world’s most vulnerable economies are greatly to be welcomed, they are only a start in addressing such problems.

Market-based solutions do not, however, allow us (anywhere in the world) to avoid social welfare decisions. One question is how any revenues generated by these measures – e.g. via a carbon tax – can be reallocated within societies. In theory, such revenues could be a helpful tool in reducing the social costs involved in large-scale restructuring of economies as part of the sustainable transformation. But there will always be the risk of such funds being diverted into other uses, and there may be other efficiency arguments against such hypothecated taxes.

Achieve transparency – on both costs and growth implications

Another issue that needs addressing: cost transparency. We already know that the costs for private households of some environmental policy shifts can be very large. But how precisely these costs are imposed on households is often not clear. Some costs are very visible – higher taxation of household vehicle usage, for example. But the impact of other policy measures may be concealed, for example if households are not the ones bearing them directly (e.g. policy raising the costs of inputs for firms, rather than final consumption of goods and services). In this case, householders can involuntarily provide at least a temporary (an involuntary) cushion for firms as they increase the prices of emissions-intensive products. (Although it should be noted that the price mechanism will still provide incentives to firms to find less emissions heavy production alternatives, to maintain their competitive position. Higher prices may also help signal to consumers the environmental costs of a product, encouraging them to switch consumption).

This issue of transparency needs also to be applied to the bigger issue of growth itself. Historically, economic policies have also assumed that economic growth is beneficial in that it makes society as a whole better off, with environmental and social costs generally ignored. We know from experience that trying to identify and support future growth sectors is difficult as we cannot foresee the future. But now, given the enormous task of shifting the global economy to more sustainable models, we also need to consider multiple other aspects of growth, including potentially how to limit or shift consumption patterns. Changing the direction of the economy in this way will take time: it is not like an economic stimulus programme that produces results in a short amount of time.

Policy: reconciling market and community-based decision making

The last point to consider is to what extent market-based approaches such as those discussed above can co-exist with community-based, localized decision making (as proposed, for example, by Elinor Ostrom). Many local communities have organized successful transition projects. The advantage of these is that it is often easier to organize in small communities and direct involvement in funding may increase feelings of responsibility and thereby also support.

But do these approaches have the potential to be used more generally? It is possible to identify many inherent tensions here. For example, funding these projects is achieved through members of a community, perhaps in consort with international agencies. But bigger projects ultimately may require centralized financing from tax revenue, taking away the local character of a project - and it also far from a given that all communities, municipalities, etc. will be able to agree upon what needs to be done. But I still see great benefits of a localised approach, in that it should allow us to see which approaches work well and which don’t. We need to recognize that we cannot perfectly forecast the future, and that we will need to amend policy as we understand environmental issues better.

Think hard about solutions – but act quickly

To summarize, I do not see the recent social pushback over proposed environmental measures as wholly negative. It reminds us that we need to think hard and find the best ways to tackle the consequences and risks of climate change. Social costs from change will be major, even if assuming an effective (technological) path can be found for economic transformation. So, instead of relying on a centrally-driven directional approach, we need to establish how to use market-based tools in a social market context. Firms may be effective in finding most efficient way of adjusting and exploring new ways of production – but we also need to consider the social implications, direct and indirect.

There are two other major considerations which should guide action. First, time: we don’t have much left: latest estimates suggest, for example, that for a 50% chance of keeping global warming to 1.5oC, we can emit only a further 250GtCO2, equivalent to just six years of global CO2 emissions at current levels. Second, we have to acknowledge that this lack of time will have an impact on how the accumulation of knowledge leads to economic transformation. How do we speed up knowledge accumulation and dissemination – and how to we ensure that policymakers respond quickly to the insights revealed by it?

Incorporating and weighing all these factors will be necessary to establish a consensus in societies on what to do about a changing climate. It won’t be easy, but we need to work out ways to do it.

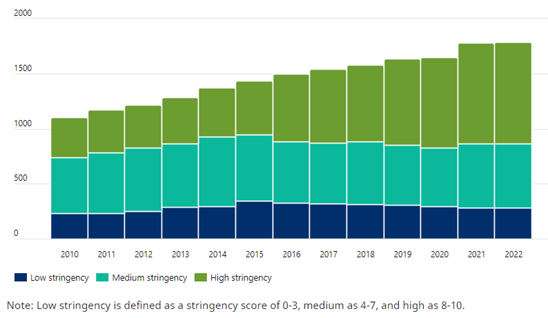

Source: OECD (2023)

Photo by Google DeepMind

References

Karan, V. (2023, October 3). Social Cost of Carbon: The figure We need to know | Earth.Org. Earth.Org. https://earth.org/social-cost-of-carbon/

Lamboll, R., Nicholls, Z., Smith, C. J., Kikstra, J., Byers, E., & Rogelj, J. (2023). Assessing the size and uncertainty of remaining carbon budgets. Nature Climate Change, 13(12), 1360–1367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01848-5

Rennert, K., Errickson, F., Prest, B. C., Rennels, L., Newell, R. G., Pizer, W. A., Kingdon, C., Wingenroth, J., Cooke, R. M., Parthum, B., Smith, D. J., Cromar, K., Diaz, D. B., Moore, F. C., Müller, U. K., Plevin, R. J., Raftery, A. E., Ševčíková, H., Sheets, H., Stock, J.H., Tan, T., Watson, M., Wong, T.E., Anthoff, D. (2022). Comprehensive evidence implies a higher social cost of CO2. Nature, 610(7933), 687–692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05224-9

Richardson, K., Steffen, W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S., Donges, J. F., Drüke, M., Fetzer, I., Bala, G., Von Bloh, W., Feulner, G., Fiedler, S., Gerten, D., Gleeson, T., Hofmann, M., Huiskamp, W., Kummu, M., Mohan, C., Bravo, D., . . . Rockström, J. (2023). Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances, 9(37). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh2458

Supply of critical raw materials risks jeopardising the green transition. (2023, April 11). OECD.org. https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/supply-of-critical-raw-materials-risks-jeopardising-the-green-transition.htm

The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.). https://sdgs.un.org/documents/sustainable-development-goals-report-2023-53220