Hong Kong, the AIIB, and the Evolving Geography of Finance: A World Financial Center in the Making?

Gregory T. Chin explores Hong Kong’s lobbying for a special role in the AIIB and in the Belt & Road strategy, the number of visits by Asian state leaders, and the corporate realignments across Asia.

During my recent visit to Hong Kong in mid-June (2017), the government announced that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) had joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the new multilateral development bank that was launched in December 2015.

AIIB was founded under China’s international lead to foster sustainable economic development and address “infrastructure needs”, broadly defined, across Asia, and potentially outside of the region. AIIB offers sovereign and non-sovereign financing for sustainable projects in energy and power, transportation and telecommunications, rural infrastructure and agricultural development, water supply and sanitation, environmental protection, and urban development and logistics. The bank operates from the understanding that it can help stimulate growth, create wealth, and improve access to basic services for people in the region by strengthening interconnectivity and economic development, through improvements in infrastructure and other productive sectors.

Hong Kong is the latest to join along with four other new Asian members to the bank, Afghanistan, Armenia, Fiji and Timor Leste and eight others spanning several continents— Belgium, Canada, Ethiopia, Hungary, Ireland, Peru, Sudan and Venezuela.

The news that Hong Kong has been admitted to the AIIB as perhaps the seventieth member may sound unremarkable to the casual observer. The bank’s membership has grown steadily since it was launched in 2015, now standing at 80 approved members from a founding membership of 57.

Amid the flurry of new memberships, it is possible that Hong Kong’s AIIB membership might be seen as quite routine. Except that underpinning this move is a bigger realignment of the geography of world finance, and global power that is currently underway. There is also a story of local strategic foresight and Hong Kong policy and corporate entrepreneurialism, and an ambitious schema of pan-regional transformation within which to situate the new Hong Kong agenda. Moreover, at the same time that Hong Kong is pursuing its new renewal agenda, traditional centers of finance appear to be waning or have made policy decisions that reduce their ability to take advantage of new opportunities.

Other Financial Centers

Major shifts are afoot in the global financial system. Large global banks are preparing to leave London, as hopes fade for a transitional Brexit deal. Downing Street appears to have waited until too late to convince the major banks that it has a strategy to soften the impact of Brexit, before the banks start shifting operations elsewhere.

According to Reuters, senior executives at five of the large banks in the City believe that a staggered deal on leaving the European Union is likely to be agreed upon only late in the negotiations with Brussels. One bank executive remarked, “the timeframe for when we wanted a transitional deal has already passed”; the bank decided to move hundreds of jobs to continental Europe regardless of what the UK government does.

The head of Goldman Sachs, which employs 6500 staff in the UK, has warned that London’s financial center will “stall” due to the Brexit process. It too has contingency plans to relocate people depending on the outcome of the negotiations. In January 2017, the HSBC chief executive said that its trading operations, which generate about 20 percent of revenue for the investment side of the bank in London, may be moved to Paris. The same month, the chairman of UBS said that about 1000 of the bank’s 5000 jobs in London could be at risk. In May 2017, JP Morgan confirmed that it would move hundreds of jobs from the United Kingdom to the EU due to Brexit. Even the policy chair at the City of London Corporation, Catherine McGuinness, says that, “it is entirely right that firms plan for all negotiation scenarios and assess what impact this might have on jobs in the UK. Some of these may relocate to other global financial sectors and the City might not grow as quickly as it otherwise would have done.”

Singapore, one of the key financial centers in Asia, also seems under pressure of late, pressures that have to do with Singapore’s political-economic geography both with its immediate neighbours in Southeast Asia, and its uneasy position between the United States and China. How Singapore manages these challenges will have a great bearing on Singapore’s role within the global financial system.

In the era of the Donald Trump presidency in the United States, Singapore, which has thrived in the long boom era of trade liberalization, openness and global integration, is wondering how it can continue to prosper if the countercurrents to globalization prevail. [1]

According to Manu Bhaskaran, a Singapore-based partner at Centennial Group, an economic consultancy, the challenge for Singapore, including its future as an international financial center, is really its “value proposition,” “which is a combination of competitiveness – including costs – and how the city has chosen to position itself.”

Hong Kong’s Continuing Renewal

Deeper changes are also underway in Hong Kong. However, they are not necessarily the items that have been the focus of the mass media.

Passions were stoked by the twentieth anniversary of the territory’s return to China. Much of the recent international news-cycle about Hong Kong has been dominated by stories about Hong Kong’s political present and future, societal tensions within the city, and the current generation of youth struggles in the territory (Penguin Books has seemingly dedicated a new series of short books to these themes, and the august China Quarterly has just re-posted a set of excellent scholarly articles in commemoration of the 20th anniversary).

But an equally pivotal storyline is the city’s ongoing challenge to maintain its relevancy in the world – especially as a center of international commerce and finance in the face of stiff competition from other financial centers inside the region, outside of Asia, and with Shanghai’s continuing rise – while also maintaining its unique local cosmopolitan dynamism.

Hong Kong was fuelled by mass migration from the People’s Republic from the late 1940s onwards that brought hard-working Mainland talent to the British colony for half a century. In the 1980s, Hong Kong became the shop window for the Mainland factory, and transformed itself into a key shipping and transport hub. In the last period of colonial rule, a lot of investment was poured into modernizing infrastructure and public transport systems in the territory, bringing significant improvements in the livelihood of local residents. In the 1990s and first-decade of the 2000s, the city repositioned itself as the bank and financier for the juggernaut Chinese domestic economy.

Hong Kong is now evolving again. The changes in Hong Kong, the emerging elements of its latest renewal story are partly influenced by the changes happening in the other financial centers, but also, as we will see below, guided by the new regional agenda emanating from Beijing, and by Hong Kong’s proactive agency, and that of others inside the Asian region, in pursuing the opportunities that are presented by the Belt & Road initiative (BRI) and by the AIIB.

Joining the AIIB

From the vantage of a broader global and political economy perspective, there is deeper meaning to Hong Kong’s new AIIB membership. Beijing seems to have either assigned, or agreed to, a new role for Hong Kong in the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI).

In joining the AIIB as of June 2017, Hong Kong agreed to pay HK$1.2 billion over five years as its contribution to the new multilateral bank. Hong Kong has an ambitious agenda: it is seeking to be an alternate governor on the bank’s board, giving it a bigger say in the bank. Moreover, The South China Morning Post (SCMP) reported that Hong Kong is now also lobbying the AIIB to establish a regional office in the city, and to move part of its treasury operation to the Hong Kong.[2]

According to Hong Kong Financial Secretary Paul Chan, Hong Kong has conveyed its wishes to both AIIB president Jin Liqun and China’s Finance Minister Xiao Jie. Hong Kong’s finance chief said that Beijing gave a “positive” response to the proposal. “They know our advantages, compared with cities like Shanghai, we have the advantage… of our wider reach to international investors, in particular institutional investors.” Chan added that Hong Kong also has the “China advantage” over cities like Singapore and London.

Interestingly, when the AIIB president was asked earlier (April 2016) by the SCMP whether the AIIB would open a regional office in the city, he side-stepped the question, answering, “It does not matter if there is a headquarters in Beijing and… another office in Hong Kong. It depends on whether Hong Kong can provide services for the AIIB”. According to the Post, Jin also noted that, “Stability is also very important”.

These reservations notwithstanding, Jin gave assurances that, “We [AIIB] will certainly have a special seat for Hong Kong. It’s already in my heart… Please trust us, we will work hard and solve Hong Kong membership as soon as possible.” Jin indicated that he hoped the AIIB could raise funds and conduct currency trading in the city: “Hong Kong has good qualifications and it is totally reasonable to move [some] capital to be managed by Hong Kong.” He also suggested that the city could serve bond issues, and handle other capital management for the AIIB, and the new multilateral bank could work with banking networks in the city. The AIIB president also acknowledged that Hong Kong has experienced consulting and legal firms, which could prove useful if the new bank faced dispute arbitration.

Three Supportive Trends

Beyond the policy intentions and proactive interventions of city leaders to carve out a new role for Hong Kong in the AIIB, and in the BRI, the likelihood that Hong Kong will be effective in developing the new role appears to be bolstered by three enabling factors. Based on my recent field interviews in Hong Kong, and assessment of the related qualitative information and data, three supportive trends stand out.

First, are the fundamentals, and the strategic analytical capabilities of Hong Kong researchers in deciphering the main factors that determine the potential demand for BRI financing and investment from the firms and sectors across the participating economies. In a novel Working Paper, published by the Hong Kong Institute for Monetary Research (HKIMR, the research institute of the HKMA), Hongyi Chen of the HKIMR and coauthors, Tianjiao Jiang at Hang Seng Bank and Chen Lin at the University of Hong Kong, quantify the financing needs in the Belt & Road countries and industries. They use firm-level data from 2009 to 2014, to identify financing constraints of firms in the Belt & Road countries, and have constructed a “Financing Needs Index for Belt & Road Countries.” In so doing, they are able to highlight the character of the financing needs across 36 countries, 80 industries, over the 6-years. Further incorporating information from World Bank Enterprise Surveys, they also offer an “Augmented Financing Needs Index” for 56 Belt & Road countries. Their paper recommends to the partner countries that they can attract more financing for their indigenous firms by pursuing further financial liberalization, improving their business climate, and the related institutional quality.

Second, Hong Kong’s latest renewal efforts are aided by agency trends on the demand side. State leaders of Asian nations have been visiting Hong Kong, with increasing regularity, seeking investment and financing from Hong Kong for their own infrastructure and national development programs. In the period leading up to the Belt & Road Forum in Beijing, Indonesian President Joko Widodo visited Hong Kong from April 30 to May 1, 2017, and then Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte visited the city two weeks later, and they each met with key corporates and potential financiers and investors in the city.

The Indonesian president has ambitious plans to transform Indonesia’s infrastructure in ways that dovetail with the China-led Belt & Road initiative. Widodo has met with Xi at least five times, including attending the BRF in May. He has also spoken about Hong Kong firms in positive tones: “Our Hong Kong investors [in Indonesia] are very strong. They believe in long-term investment. They respect our laws, they respect our culture and society.” (Indonesia and Hong Kong also share the organic link of more than 172,000 Indonesian migrant workers living in Hong Kong)

En route to Beijing for the BRF last May, the Philippine president also made a three day stopover in Hong Kong. Although his visit was classified as a “non-official visit,” as Mr. Duterte was not expected to meet with Hong Kong government officials, his trip was nonetheless the first visit of a sitting Philippine president to Hong Kong, and the security measures deployed by Hong Kong authorities were the same as for the Indonesian President, including VIP protection, and the number of police units on duty.

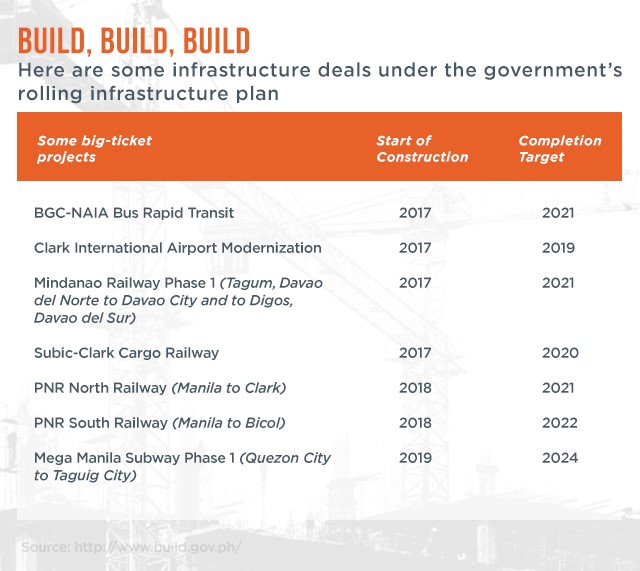

President Duterte broke from his predecessor’s confrontational approach to relations with China, and in 2016, during his official visit to Beijing, China pledged US$9 billion in loans to the Philippines. At the BRF in May 2017, Duterte witnessed the signing of a P3.6 billion (US$7 million) grant for two bridges in metro Manila. Duterte also has his own ambitious infrastructure plan, which was announced in April 2017, called the, “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure plan, or “Dutertenomics.” The Philippine President has been meeting with international investors and media to present the main elements of the program (listed in the Table below), which carries a price tag of US$160 billion and is seen as separate from the Philippine government’s existing PPP (private-public partnership) program funding for infrastructure. Duterte presented the program at the ASEAN annual meeting, this April in Manila, which he chaired. Philippine strategic analysts note that the “infrastructure-driven” Belt & Road initiative dovetails with the Duterte administration’s infrastructure plans, and they suggest that the payoff for the friendly diplomacy with China should be support for components of the president’s infrastructure plan.

After attending the BRF, Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif treaded a similar path as the Indonesian and Philippine heads of state, also visiting Hong Kong to seek investors for his country’s infrastructure (and property market) projects. Pakistan’s Commerce Minister Khurram Dastgir Khan said that he hopes the “long friendship” with Hong Kong will be turned into an “economic partnership”, with Hong Kong a key player in transferring capital, expertise and constructing infrastructure. Khan said, “We are hoping that some of the future infrastructure will be built by Hong Kong companies in collaboration with Chinese companies.”

When the Pakistan Prime Minister and Commerce Minister met with 60 companies based in Hong Kong and the Mainland at the “One Belt, One Road Pakistan Investment Forum” in Hong Kong, which highlighted investment opportunities emerging from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Minister further suggested that Hong Kong has a “very important” role to play, in providing technical, legal, architectural and planning services for a forthcoming “real estate boom” in Pakistan.

Behind the scenes, it is quite likely that Beijing has directed Pakistan, Indonesia and the Philippines to seek investment from companies in Hong Kong in order to encourage diversification in the external financing for the infrastructure and development projects of the partner Belt & Road nations. Considering the rising expectations from partner nations that China’s national authorities are now facing, it is especially crucial, moving forward, for Beijing to bring in the strategic assessments of private corporates and key financial institutions in Hong Kong into the discussions with Pakistan, Indonesia and the Philippines, in order to test or strengthen the “bankability” of the proposed projects. Related, the Pakistan commerce minister has flagged that, “We are also hoping to use the Hong Kong stock exchange to list some of the major energy infrastructure we are building and to be able to raise money internationally for them.”

The third trend supporting the renewal agenda in Hong Kong is that impactful market actors in Hong Kong are repositioning for this push, on the supply side, and strengthening their capabilities to intermediate between demand and supply. Bank of China Hong Kong (BoC HK), the second largest commercial bank in the city, and actually one of the key strategic corporates in Hong Kong, is leading the pack. BoC HK is in the process of acquiring its parent Head Office’s (BoC China, Beijing) network of branches in the ASEAN region, which started with the Malaysia and Thai units in June 2016, but is also planned for the BoC branches in Singapore, Cambodia, Vietnam and the Philippines – six nations in total. In July 2017, BoC HK also took over the Indonesia business of BoC. BoC HK has also sold its subsidiary Nanyang Commercial Bank, and its stake in Chiyu Bank to free up capital to expand further across the Asian region.

BoC said that the proposed transfers further expand the business reach of BoC HK into the ASEAN region, strengthen the Bank’s regional customer service capabilities, will boost product innovation and market competitiveness, and drive accelerated growth in the region. BoC senior management also highlight that the expanded operations of BoC HK will also enable the bank to take on more Belt & Road-related financing projects, and that the six countries are among the key markets in Asia where there will be “significant business opportunities in infrastructure financing projects, as well as more opportunities for corporate finance, project finance, investment services for central banks and sovereign wealth funds – which will feed, in turn, into the BoC’s RMB internationalization business strategies.

BoC HK, which was already ranked by The Asian Banker as “the strongest bank in Asia-Pacific and Hong Kong” for successive years, has pledged to continue to assess other ASEAN assets and look to expand its turf, “more turf means more opportunities.”

Despite the recent sluggishness in the Hong Kong economy, BoC (Head Office) and BoC HK remain optimistic about the outlook for Hong Kong, noting that about 60 percent of Mainland companies continue to opt for the city as their first choice for their regional headquarters as they push overseas. The senior vice president of BoC HK remarks, “As the world’s third-largest financial center, Hong Kong would not be easily displaced by any mainland city. There will still be some distance for other competitors to catch up with, in playing this role.” He added that Hong Kong, is a “key window”, and “super-connector” in the Belt & Road strategy, and that the “central government will release supporting policies to continue to bolster Hong Kong’s economy.” Hong Kong is thus “still a good place for Chinese corporates to go out and investment.” The BoC HK’s network in Hong Kong – involving 220 outlets and six business centers – is therefore a key asset.

Interestingly, Barclays Bank, in a research report by its equity analysts, notes that BoC HK has a “competitive edge over other Mainland and regional banks to finance Belt & Road opportunities”, due to its sizeable funding base in US dollars and offshore RMB, which derives from it being the sole clearing bank in Hong Kong. Barclays is anticipating that BoC HK can quickly become a niche player in the ASEAN region in the near term, based on targeting large corporate clients, and financing infrastructure projects, as well as by tapping into the wealth of overseas Chinese retail customers.

Summary

Other international financial centers in Asia – rivals to Hong Kong – are likely to stand up and take notice of Hong Kong’s robust lobbying for a special role in the AIIB and in the Belt & Road strategy, the number of visits by Asian state leaders, and the corporate realignments in Hong Kong and across Asia.

It will also likely not be missed that there may be a perception that the financing needs of Indonesia and the Philippines have not been adequately met, in the past, by other financial centers, and their national leaders are going to Hong Kong, either on their own, or encouraged by Beijing, to seek financing and investment for their national infrastructure and modernization projects.

For the other financial centers and major economies further afield, including those which are currently engrossed in their own turmoil, such as the Brexit transitions, or worried about renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement, or ensuring that America “gets a better deal”, it will be important not to miss (once again) the emerging developments in the “Far East.” Perhaps there is a deeper message in the Hong Kong story about the need even for sovereign nations to respond proactively, strategically, and rapidly, to opportunities and challenges in the new uncertain world.

Gregory T. Chin (PhD) is an Associate Professor of Political Economy in the Department of Political Science, and Faculty of Graduate Studies at York University (Canada). His principal research interests are in the areas of international and comparative political economy with a focus on China, Asia, the BRICS, international money, finance, and global governance. He is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Institute at the Johns Hopkins University, School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), and co-directs the “Emerging Global Governance” (EGG) Project, hosted by Global Policy. He is on the International Advisory Board of the journal Review of International Political Economy, and the Editorial Board of the journal Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations.

Photo credit: Foter.com CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication

Notes

[1] I thank Richard Stubbs for bringing this news article to my attention, Jeevan Vasagar, “Asian Dynasties: Battle for the Soul of Singapore”, The Financial Times, July 9, 2017.

[2] Catherine Wong, “HK Pushing for Regional AIIB Office, Chan Says”, The South China Morning Post (print edition), June 18, 2017, p.3.