Bob Marley and the “Other”

Brian Stoddart on why the study of popular culture has much to offer the world of international affairs and development.

While we know instinctively that popular culture in all its forms reflects and shapes its generational social and political contexts, now and then a special moment jolts us into deeper consideration. In Australia, the recent Taylor Swift tour prompted a slew of opinions on her social and economic impact, some casting her as an agent of inclusion and unity as well as a healer of the national purse. In times past, similarly, predecessor rock stars ranging from Elvis Presley through the Beatles to Cher and Coldplay have been labelled as “the voice of a generation”, as have more genred artists like Willy Nelson and Jimmy Buffett.

That said, there was for a long time a “first world” slant to all that with knowledge of major figures like, say, Johny Clegg and Juluka in South Africa along with other African names like Angelique Kidjo, Yousssou N Dor, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Fela Kuti and Ali Farka Toure confined to “world music” cognoscenti.

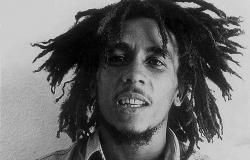

Arguably, the one artist who changed that was Bob Marley who died at just thirty six in 1981, having alerted an entire global generation to what was once called the “third world”. Perhaps coincidentally, his 1970s impact coincided with that of Edward Said whose 1978 Orientalism upended so many views and practices on the researching of and writing about other cultures. Fittingly, perhaps, their influences and impacts are still contested today.

The ”special moment jolt” that prompted this reflection was seeing the Bob Marley: One Love movie directed by Reineldo Marcus Green (of King Richard note); produced collectively by the Marley clan led by Ziggy and Rita; executive produced by Brad Pitt among others; and written collectively by Terence Winter (Boardwalk Empire), Frank E Flowers, a Cayman Islander who works in the United States, and Zach Baylin who worked with Green on King Richard.

Here, it must be said the film is not that good. The family domination in production has helped an overall hagiographic effect emerge; the jointly written script is a collection of vignettes rather than a holistic arc; most characters go undeveloped; and the wonderfully heavy Jamaican patois dialogue makes it difficult for some viewers to keep up.

Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian declared the overall result “ploddingly solemn.” In the New York Times, Amy Nicholson thought the script delivered a “patchy and unsatisfying” film. The independent reviewer Roger Ebert saw only a “horrendous, unshaped stream of events.” Now, these and others like them are professional film critics working within technical and professional analytical structures, but it is hard to disagree. I left the theatre thinking so much more might have been achieved. And there was also the never-ending complexity of historians watching films that allegedly recreate times and peoples past.

Curiously, though, the influential if problematic review site Rotten Tomatoes shows an audience score of 92% for the Marley film, against a much lower critic score. Among the many audience comments (and a few do hate the film), some thoughts recur – if “you knew” Marley and his music then the film would resonate with you, because he was “one of a kind” who had a massive impact on his generation.

Indeed. When Marley with Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer began their recording careers in mid-1960s Jamaica, Martin Luther King was bringing wider attention to the place of African Americans in the United States, the full impact of the Windrush generation was emerging in the United Kingdom, and global music was dominated by both those countries. Jamaica itself was already in the economic throes that would produce so much tension over the next decades, being almost the model of the so-called “third world” problem.

By then the British world, Commonwealth following Empire, “knew” about the Caribbean or “West Indies” through another popular culture form, cricket. West Indies in 1950 beating England in a series at “Home” for the first time inevitably formed part of the emerging dialogue about political independence for Caribbean nations. That success was offset by persistent ideas about West Indies cricket being flashy, ill-disciplined and individualistic, the result of English cricket from the start being seen throughout the Empire as the yardstick for perfection. There was no room here for the subject/subaltern to create new forms. That was why the 1959 appointment of Frank Worrell, a black man, as West Indies captain assumed such importance.

In cricket, that is, by the time Bob Marley went public, West Indies were still seen as being in tutelage and scarcely ready, therefore, for wider independence. Notably, of course, such wider knowledge as there was concerned “West Indies” rather than the individual countries that made up that entity (that still exists only for cricket and the University of the West Indies). As Said might have put it, the prevailing view was defined by a cultural stance that excluded thoughts from the “Other.” That stance, too, was restricted to a cricket world marked at “Home” and, to varying degrees across the Commonwealth by colour, class and caste divisions. The knowledge base, then, was limited.

Marley changed all that in two major ways: he shifted the cultural base of knowledge about Jamaica and West Indies more broadly; and globalised that understanding from its British world platform.

In 1979, for example, around the time this film is focussed, Marley played one concert in New Zealand. To this day, that is seen as having catalysed Maori and Pasifika activists and created a musical inheritance there based in equality and human rights. Much the same story emerged in Australia. In Vanuatu now, Stanleyson Antas of reggae band Stan and the Earth Force emphasises the importance of Marley in the island’s ongoing struggle for independence from France. And the continuing impact across Africa goes without saying.

Across all locations he drew attention to the state of things in his own country and, by definition, sharpened awareness of countries in similar positions across the global south. The music helped precondition anyone with an interest in those countries and their broader challenges, but among other things the film misses the edge to be found in places like Jamaica then, even if it does highlight the political violence Marley set out to help calm.

My first trip to Jamaica, on cricket research, followed Marley’s death and the economy was in trouble, largely because collapsed bauxite prices hit GDP growth, triggered social stress and sparked a repressive IMF regime that imposed tough aid and development reform measures. One resident at my hotel would arrive Monday morning from New York, travel to and from his financial restructuring office until Friday, then fly home for the weekend. That was essentially all he saw of Jamaica. Yet a couple of blocks away, the impacts of all this were everywhere to be seen.

As Marley told us, the people were suffering.

At a hotel not long abandoned by the Hilton chain, Sandi and I discovered that the cost of our chicken dinner matched our waiter’s monthly salary as the Jamaican currency plummeted against international ones. Ships had long abandoned the place, but cruise centre stallholders still turned up showing their wares, and bar buying everything each of them produced we felt powerless.

As the film suggests, Marley was about peace and unity as well as love, but that was always a tough struggle for Jamaica. Walking through town one morning I passed a music shop from which blared some magnificent reggae I did not recognise, so asked the owner who happened to be a Rastafari. “What the fuck do you want to know for?” came the reply.

Later on in Barbados, we befriended a young and rare Rastafari there who candidly noted he would never own a property or travel widely, have a regular income or gain any reasonable education. Local conditions prevented that.

Those were the very things Bob Marley made people around the world aware of and that is why his music endures.

That music saves Bob Marley: One Love. The best scenes are all about the music, and illustrate why the man created such excitement in concerts and recordings, because there was always a meaning and a message remarkably close to the surface, both of those explanatory for and relatable to his audiences. He “knew” the global south and could explain it to a vast range of audiences around the world.

That music is still electric. There were just half a dozen of us in the Fremantle theatre where I saw the film, every one of us moving when all the Marley favourites came on, and one couple danced out of the theatre at the end.

For me, Bob Marley was one of the important sources in becoming aware of and understanding the world of the “Other”, and that is why the study of popular culture has much to offer the world of international affairs and development, even if this film does not do it perfectly.

Brian Stoddart is Emeritus Professor at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia where he was Vice-Chancellor, and a noted pioneer in studying sports culture. He has also worked on aid and development programs in Jordan, Syria, Laos and Cambodia, while his original research field was on the political history of India. Brian Stoddart is also a competition-winning screenwriter and crime novelist.

Image: WikiCommons Public domain.