UN Women makes Norm Change central to its mission

Duncan Green explores an event and paper on 'Social Norms, Religion and Family Laws in the MENA Region'.

Bafflingly, I was recently invited to an online ‘Expert Group Meeting’ to help UN Women flesh out a really important new strategy – making norm change central to its role. This from the Concept Note for the session:

‘In recognition of the emerging emphasis on an articulated approach to social norms in international development and acknowledging that discriminatory social norms are a key barrier to making progress on gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls, UN Women has set attitudes, norms and practices that advance gender equality and women’s empowerment as one of 7 systemic outcomes to be pursued in its strategic plan for 2022-2025.’

This strikes me as both exciting and scary. Exciting because a lot of players in the aid/development/social change sector are starting to take norm change seriously, which I think is an important recognition of a vital driver of social and political progress.

Scary, because although, post-Brexit vote and (hopefully) post-Trump, progressive activists realized they had got too bogged down in the details of policy advocacy, new laws etc etc and were blindsided by big populist norm-based movements, we are only just scratching the surface on how to ‘do’ norm change – how to intentionally shift norms in a progressive direction. My gut feeling is that to do this well, we may have to jettison many of the approaches and organizing models of traditional advocacy, but it will be fascinating to see what UN Women conclude on this.

There were a lot of academic papers commissioned for the discussion, which will all be published in due course (check out UN Women’s excellent Discussion Paper series here). The one that stood out for me was How Does Change Happen? Social Norms, Religion and Family Laws in the MENA Region, by Marwa Sharafeldin, an Egyptian visiting fellow at Harvard. It’s still in draft form, but here are some excerpts, with Marwa’s permission

‘Looking closely at Muslim family laws in the MENA region, we find an underlying philosophy and worldview on gender relations that has its origin in a patriarchal human reading of Islamic religious texts – as opposed to a more egalitarian reading of these very same texts. Today, these laws are mostly premised on a man-made juristic equation created by classical jurists over hundreds of years whereby, simply put, a man is obliged to provide financial maintenance in return for obedience by the woman. This patriarchal juristic reading of Islam’s sacred texts is still alive and kicking in the majority of contemporary Muslim family laws and practices, legitimating male guardianship and authority over women.

Whether this was the intent of the sacred texts or not, for now this equation with its hierarchical view of gender relations remains the lynchpin upon which most of the contents of Muslim family laws, norms and gender relations are premised. Another area where we see this equation manifest in contemporary laws, not just in family laws, is the right of the male guardian to ‘discipline’ the woman, also known as ‘striking’ or ‘lightly beating’. According to the Penal Code of Iraq: “There is no crime if the act is […] the punishment of a wife by her husband.” A report by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) on women and development quotes a 2017 World Bank survey which shows that an alarming 28.2% of women in OIC countries find that a husband can be justified in beating his wife if she argues with him.’

‘There is however a reformist gender discourse that takes gender justice and equality as the premise of gender relations in Islam. It finds that gender inequalities found in the traditional discourse are not divine injunctions, but rather are human constructions created by male jurists that contradict the divine intent of Islam’s message. It is a discourse that deconstructs religious knowledge focusing on how knowledge was produced in order to reconstruct an alternative knowledge that comes closer to the purposes of Sharia.

The question here is, despite the presence of both a traditional and a reformist Islamic discourse on gender relations, both rooting themselves in the sacred texts, why was one made more dominant than the other in our day-to-day lives?

‘What we end up with is in fact a political question, not merely a theological one. The demarcating lines between politics and religion become significantly blurred when state institutions including religious ones purposefully pick up a particular religious discourse and endorse it in their laws and policies regulating society and its gender norms. It is this co-optation of religion by politics to serve certain interests that has made Muslim family laws and norms particularly resistant to reform.’

How should UN Women think about change in this kind of context? Sharafeldin provides a great case study of Musawah, the global movement for equality and justice in the Muslim family, which was launched in Malaysia in 2009.’

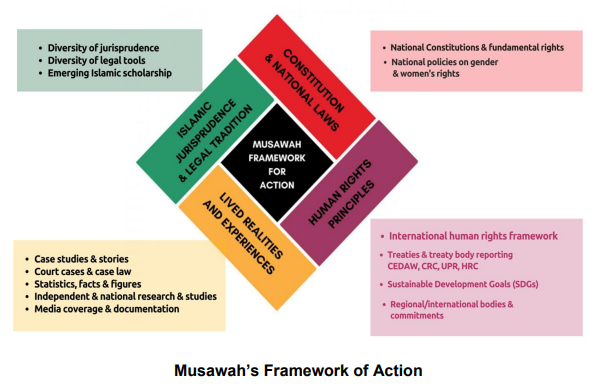

‘For several years before its launch, the 12 Musawah co-founders from eleven countries, representing the different regions of the world, spent a lot of time honing the Musawah Framework of Action. The framework brings together Islamic teachings; human rights principles; constitutional and legal guarantees of equality and the lived reality of women and men today. It was conceptualised and written through a series of meetings and discussions with Islamic scholars, academics, activists and legal practitioners from approximately thirty countries. It was also built on the successful experience of the Moroccan women’s movement that culminated in the reform of the Moroccan Muslim family law in 2004.

To explain this framework using child marriage, in any given context the ‘lived reality’ of child marriage will interact with ‘Islamic teachings’ determining which elements of Islamic knowledge reformers would engage with and give priority to whilst addressing the issue (for example using recent historical scholarship proving that Aisha the Prophet’s wife who was thought to have married him at age 9, was in fact married not less than 19. This choice will also interact with and activate the ‘human rights’ treaties that this particular country is party to (e.g. the Convention on the Rights of the Child, CEDAW etc.), while taking into consideration the ‘legal framework’ of constitution, laws, policies and decrees governing children and marriage in that context (e.g. child law, health regulations, educational policies etc). Depending on the interaction between all these four corners within that particular socio-political and economic context, a country may then decide to: completely ban child marriage below the age of 18; allow it unconditionally, or allow it with exceptions that a judge may authorize. Reformers balance these four corners together in the best way possible to come out with the best kind of change or reform they are able to extract at that political moment.

What is interesting here is Musawah’s structural approach to engaging with religion. It starts from lived reality, its problems and possibilities, then works with religious discourse and sacred texts to try and address these lived reality issues. In so doing it approaches the religious ‘text’ with the ‘con-text’ in mind and brings into the conversation a feminist perspective along with human rights and national laws as well. It engages in a structural way with established religious knowledge, deconstructing it and understanding how it was built and influenced by patriarchal contexts over time, in order to reconstruct an alternative religious discourse that is more aligned with gender equality and justice and hence with the ultimate intents and purposes of Sharia. In doing so, Musawah builds on Islamic legal methodologies and principles of knowledge production. ’

Musawah takes this work and engages with activists, policy-makers, parliamentarians, judges, lawyers, young women and men, providing a space for mobilizing and organizing on both local and regional levels to make these changes through joint campaigns such as the Campaign for Justice in Muslim family law. Its approach has been successfully adapted to numerous other countries, including India, Indonesia, South Africa and Egypt.

The paper concludes with some excellent thoughts on measurement, which I don’t have space to go into fully, but in brief she identifies 3 levels that can each be measured with a high degree of rigour: changes in religious public discourse on religion and gender; changes in laws and policies and changes in the lived realities of women and families in Muslim contexts.

This is going to be really interesting and important to track over the next few years, and the discussion was definitely worth the discomfort of being the only participating male in a 50+ webinar!

This first appeared on Duncan's blog From Poverty to Power.

Photo by Mihman Duğanlı