The Covid-19 Crisis should Force a Rethink of ‘Financial Inclusion’ in Global Development

Nick Bernards argues that the pandemic has exposed long-standing deep problems with the Fintech driven financial inclusion agenda.

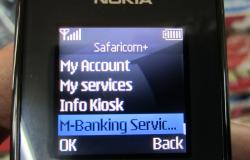

‘Financial inclusion’ has occupied a prime place on global development agendas for the last decade. Policy makers have pushed a wide-reaching agenda of promoting ‘access’ to a range of financial products for the poorest, including microcredit, but also savings, payment systems, and insurance. Increasingly, there’s been an emphasis on providing these things through new applications of mobile and digital technologies.

The present crisis underlines an urgent need to rethink this agenda.

The past few months have been very bad for many microfinance institutions (MFIs) and fintechs. Fintech lenders are in distress in Indonesia, India, and across South East Asia. A survey in Pakistan found that 90 percent of borrowers expected to struggle to make payments and MFIs expected to collect only 34 percent of payments due in April 2020.

Things are even worse for borrowers. In Cambodia, where the microcredit sector was already well into crisis territory even before the pandemic, with an average microloan debt per borrower of $3 804 (roughly double the country’s GDP per capita), the situation is dire. Already heavily indebted borrowers now face the loss of incomes, and potentially of land, homes, and businesses if they are unable to repay.

But this is more than a temporary hiccup. The crisis speaks to deeper problems.

In the first instance, the present crisis is a larger-scale version of a story we’ve seen before. Securing the involvement of private capital in the financial inclusion agenda has always entailed tradeoffs. The financial sector has generally only been interested in providing the more lucrative elements of ‘inclusive finance’. This has primarily meant high-interest loans to primarily urban consumers or scraping fees from remittance payments, rather than providing insurance to high-risk farmers. Indeed, it’s possible to read the recent embrace of fintech as, in part, an effort to get around this problem.

Fintechs promise to extend access to credit to ‘excluded’ borrowers through a hyper-individualized approach to assessing credit risk. The claim is that by scraping cell phone data or developing novel measures of personality, and developing algorithms to analyze that data, they can provide accurate measures of the creditworthiness of informal sector workers lacking conventional documentation like pay stubs, income tax receipts, property titles, or credit histories. This approach emphasizes individual personality traits and behaviours, and remains ‘dangerously hermetic’, in the words of one critic, to the actual productive capacities and economic situation of borrowers.

This can work (for lenders) when times are good and income opportunities are available and has encouraged an influx of venture capital investment in fintech firms. (Though, it remains unclear at best whether fintechs actually provide many opportunities to increase incomes that might not have existed otherwise.) It’s not a great system for anyone during a downturn. Previous national slowdowns have resulted in arrears and missed payments much like we’re seeing at the moment. In previous research, I’ve documented examples in India and Zimbabwe here. Over-indebtedness has also long been endemic in digital lending and microfinance. What’s different right now isn’t really the problem itself, but the global nature of the crisis.

Responses from microlenders and promoters so far have, maybe unsurprisingly, indicated very little willingness to rethink their basic operating model. A number of major microfinance investment vehicles -- in essence, companies that specialize in channeling money from global financial markets to local MFIs -- have agreed joint guidelines for re-scheduling payments from distressed MFIs. The heavy emphasis is on rescheduling rather than providing relief to MFIs (and by extension their borrowers). The World Bank’s Consultative Group to Assist the Poor are explicitly warning against debt relief or renewed subsidies for borrowers, urging instead that efforts to grapple with the crisis work to maintain ‘credit discipline’.

Promoters of FI and fintech are also doubling down on mobile and digital payment systems. There are renewed calls to expand the use of mobile and digital payments to administer emergency income supports. The theory is that digital payments can minimize physical contact and so are preferable to physical cash during a pandemic, and could potentially facilitate more rapid distribution of emergency aid. The World Bank is even now describing reducing taxes on mobile transactions as itself a ‘social protection’ measure. However, there are reasons to be cautious. Mobile money is maybe less overtly exploitative than, say, a usurious microloan -- although it is often a way of scraping data from small-scale transactions. But it threatens to create new kinds of exclusions. Mobile payments don’t really reduce the costs of making payments so much as shift them onto users, who are not all equally able to bear them. Indeed, recent evidence from Southern and Eastern Africa suggests that poorer users are eschewing existing fintech applications specifically because of the impossibility of using them without paying for expensive smartphones and carrier plans.

But more fundamentally, the current crisis throws into sharp relief how impoverished the conception of poverty reduction underlying financial inclusion really is. Recent advocates of ‘financial inclusion’ have pushed a more sophisticated set of arguments than the myths about bootstrap entrepreneurialism pushed by microcredit advocates a decade or two ago. The emphasis more recently has been on financial services as tools for ‘risk management’, enabling the poor to be ‘resilient’ to shocks and hence able to take advantage of opportunities to develop increase incomes.

However, the pandemic is revealing a lot about how risk and vulnerability are distributed systemically in the global economy. The economic costs of the virus are often being felt far from disease epicentres. We’ve seen thousands of informal construction workers in India forced to return home on foot, thousands of casual workers lose jobs in Kenyan flower fields, and thousands if not millions of garment workers suddenly out of work in Bangladesh and Cambodia as major global brands have cancelled orders. Recent estimates from the ILO have over half of ‘informal’ workers globally expected to fall into poverty. None of this is an accident in a world where major global firms, often encouraged by governments and international organizations, have spent the past few decades systematically outsourcing the riskiest and least rewarding parts of their supply chains.

We urgently need alternatives to asking individuals to develop their own tools to manage risks. Risks and vulnerabilities in the global economy are both systemic and disproportionately borne at the margins. Addressing these will require systemic, redistributive change.

Nick Bernards is Assistant Professor of Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick. He is author of the Global Governance of Precarity (Routledge 2018) and is currently writing A Critical History of Poverty Finance: Neoliberal Failures in a Postcolonial World, to be published in 2021 with Pluto Press.

Image: Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)