Mapping Stories and Cultures

This is the sixth chapter in a forthcoming e-book, entitled 'Decolonial Education and Youth Aspirations'. Marcia Camargo demonstrate how cultural cartography can be an act of cultural resistance and reaffirmation of indigenous identity.

In the field of intercultural education and indigenous resistance, projects that integrate traditional knowledge with innovative methodologies, such as cultural cartography, have been gaining prominence and proving to be fundamental for the appreciation and preservation of indigenous identities. These projects not only recognize, but also celebrate the richness of the worldviews of native peoples, promoting an education that respects and integrates this knowledge.

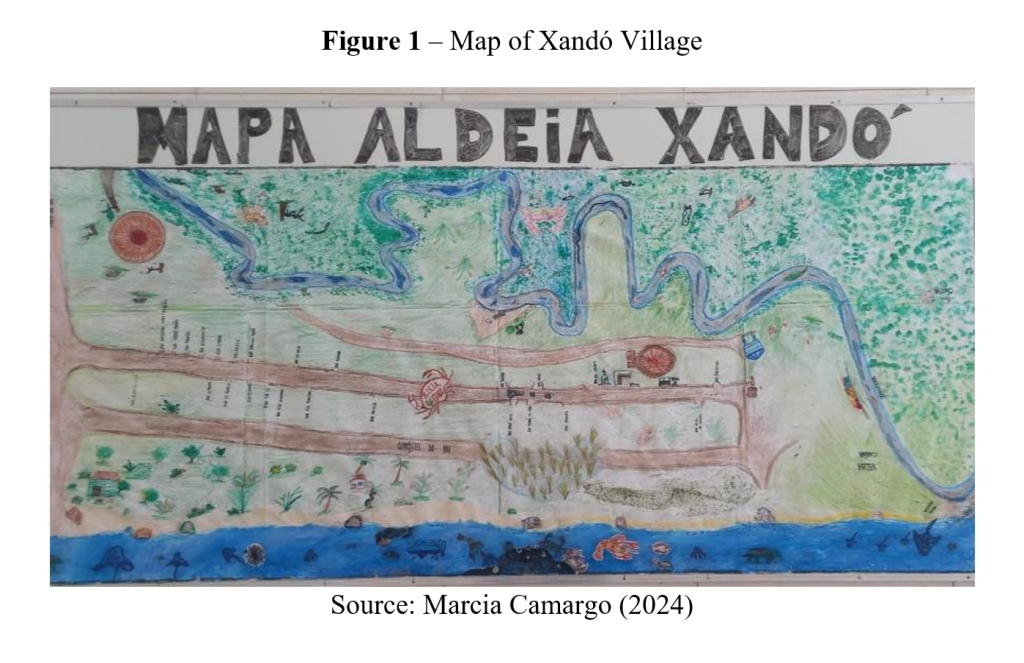

The project Cartographing Histories and Cultures, developed with 7th-grade students at Xandó Indigenous School (Bahia, Brazil), reinterprets indigenous territories through a cosmological lens, highlighting the deep connection between the Pataxó people, land, and water. More than a map, it is an educational process where students explore and share experiences, strengthening collective knowledge. Mapping thus becomes an act of resistance, reaffirming Pataxó identity and challenging hegemonic narratives that erase indigenous cultures.

Indigenous education in Brazil struggles for autonomy and cultural preservation, often facing Eurocentric curricula that marginalize indigenous knowledge. In this context, Cartographing Histories and Cultures stands out as an innovative initiative, merging indigenous traditions with formal education. By creating a cultural map, it rescues ancestral knowledge while fostering dialogue and inclusive learning that values cultural diversity.

This chapter discusses the impact of the project on strengthening the Pataxó identity and preserving their territory and knowledge. The research is based on the principles of interculturial and decolonial education, aligning with the epistemologies of the south (Santos, 2010) and the liberating pedagogies of Paulo Freire (1970). These approaches recognize the importance of valuing local knowledge and promoting an education that dialogues with the experiences and traditions of students.

"Education is not a formula, but a dialogue. Educational practice must start from the world of the student and their experiences, valuing their stories and knowledge. In this way, it is possible to build knowledge that is not only transmitted, but that is transformed into a practice of freedom and awareness" (FREIRE, 1970, p. 73).

Recognizing students as "future-makers" places education at the heart of a decolonial approach, dismantling Eurocentric paradigms and empowering them to envision equitable futures. This aligns with strengthening Pataxó identity through intercultural education that values local knowledge. Incorporating epistemologies of the South and liberating pedagogies, the classroom becomes a space for negotiating diverse perspectives, preserving indigenous knowledge, and reimagining futures rooted in history and community.

The project also draws on Bakhtin’s dialogism, highlighting interaction as key to collective learning, where Pataxó students share stories and build knowledge together. Anzaldúa’s concept of the border further reveals identity as fluid and evolving, crucial in indigenous education, where belonging and resistance continuously adapt.

The chapter aims to demonstrate how the creation of the map by the Pataxó students, in addition to being a pedagogical activity, is configured as an act of cultural resistance and reaffirmation of indigenous identity. By mapping their lands and telling their stories, students not only claim their space in the world, but also contribute to the construction of a narrative that values their culture and knowledge. This process, in addition to being educational, is a powerful testimony to the struggle for the appreciation and recognition of indigenous identities in a world that often seeks to silence them.

The chapter dialogues with theories of intercultural and decolonial education, highlighting how indigenous knowledge is often marginalized in the traditional educational system. From the perspective of the epistemologies of the south (Santos, 2010), the study proposes that the maps created by the Pataxó students be understood as a form of knowledge that breaks with Eurocentric conceptions of cartography. This discussion is essential to rethink educational approaches that often ignore the cultural richness and complexity.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2010) argues that the epistemologies of the south rescue forms of knowledge that have been historically subordinated, such as indigenous knowledge. Santos argues that these forms of knowledge are essential to thinking about a more just and egalitarian world, as they challenge the dominant narratives that often marginalize the voices of indigenous peoples. From this perspective, the study of the maps created by the Pataxó students can be seen as an effort to bring this knowledge to the center of contemporary debates about territory, culture and identity.

Studies such as those by Harley (1989) reveal that conventional cartography is not only a neutral representation of space, but reflects relations of power and domination. In this sense, indigenous cartography emerges as a representation of belonging and resistance. Through the construction of their maps, Pataxó students not only record the geography of their territories, but also express their worldview, their histories and their struggles. This cartographic process is an affirmation of identity that challenges colonial narratives and

"Cartography is not just an act of representation, but a social process that reveals the complex relations of power and domination. Maps are cultural products that reflect and perpetuate the worldviews of their creators. Thus, conventional cartography often serves to marginalize the voices of Indigenous peoples and reinforce the colonial narrative. On the other hand, indigenous cartography, by recording the territories and histories of peoples, acts as a form of resistance and identity affirmation, challenging the logic of conventional representation" (HARLEY, 1989, p. 57).

The cartographic approach proposed by Edson Krenak in his collaboration with the Munduruku people emphasizes that, for indigenous peoples, maps go beyond physical or geographical representations. They are cultural manifestations that reveal the worldview, history and spirituality of the people. According to Krenak (2020), indigenous maps are, above all, expressions of belonging, re-existence, and resistance. This perspective resonates with what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2010) calls the "epistemologies of the south", highlighting the need to value knowledge that challenges the hierarchies established by colonial modernity.

"The epistemologies of the South invite us to recognize the plurality of knowledge and the importance of forms of knowledge that emerge from local experiences. It is critical to dismantle the idea of a single truth, which often marginalizes the voices and worldviews of Indigenous peoples. The knowledge that is born from the land and from local cultures must be seen not only as alternatives, but as essential parts of a new understanding of knowledge and reality" (SANTOS, 2010, p. 45).

Bakhtin's concept of dialogism allows us to understand that the construction of the map by students is not a mere reproduction of information, but a dynamic process of interaction between different voices and narratives. Each oral history, each experience, enriches collective knowledge and transforms the act of mapping into a practice of cultural dialogue. This multiplicity of voices also reflects the struggle of the Pataxó to assert their identity in a space that often tries to silence them. Dialogue, therefore, is not only a pedagogical tool, but a political act that claims the presence and visibility of the Pataxó people.

"Dialogicity is the essence of human life, as it implies the continuous interaction between intertwining voices, in which meaning is constantly negotiated and reconfigured. Each utterance is influenced by other utterances, reflecting the multiplicity of voices that coexist in a social space. This interaction is not only a matter of communication, but an active process of construction of meaning that reaffirms the identity of the subjects involved" (BAKHTIN, 1981, p. 90).

Walter Mignolo (1994) contributes to this discussion by addressing the coloniality of power, proposing the decolonization of knowledge as an ethical and political imperative. Mignolo argues that in order to overcome the hierarchies imposed by colonial modernity, it is essential to value and recognize local and indigenous knowledge as legitimate forms of knowledge. This appreciation is crucial in contemporary debates about culture and identity, as it allows for a reassessment of historical narratives that marginalize Indigenous voices.

"The decolonization of knowledge is not a project of 'recognition' of local or indigenous knowledge, but a project of paradigm shift in which decolonial knowledges are not just an addition to knowledge, but a crucial moment in which it is recognized that knowledge is a social construction that emerges from a series of historical practices, social and political" (MIGNOLO, 1994, p. 58)

The act of creating a map by the students of the Xandó Village is an expression of decolonization that not only recognizes but also reconfigures historical and cultural narratives. By mapping their local experiences and knowledge, students are not just documenting a territory; They are also claiming their place of speech, subverting traditional representations and offering a new reading of their world. Through this cartographic practice, Pataxó students reaffirm their identity and resist marginalization, demonstrating that decolonial knowledge is not just additions, but essential transformations in the understanding of space and culture Anzaldúa's concept of the border is particularly relevant in this context, as it evokes the idea that identities are fluid and are constructed in liminal spaces, where indigenous traditions meet external pressures and new influences. Borders, in this sense, are not just divisions, but spaces of resistance and creativity, where the Pataxó people can reaffirm their culture and at the same time dialogue with the contemporary world. This dynamic of identity construction reflects the complexity of indigenous experiences in Brazil, highlighting the need for an education that recognizes and values this multiplicity.

"Borders are places of transition, of mixing. They are the space where all identities and experiences are contained, where we can see how these identities intersect and interact. A border is not just a physical limit, but a space of transformation and struggle, where oppressed voices can rise up and claim their place in society" (ANZALDÚA, 1987, p. 25).

The intersection between the creation of maps by the students of the Xandó Village and the theories of Mignolo and Anzaldúa reveals a profound process of decolonization and reconfiguration of indigenous identities. By mapping their local experiences and knowledge, students not only document a territory, but also claim their place of speech in a space historically marked by hegemonic narratives. This act is an innovative expression that challenges the notion of fixed and universal knowledge, emphasizing, according to Mignolo, the importance of situated knowledge that emerges from the interactions between indigenous culture and contemporary realities. Mapping thus becomes a practice of resistance, where Pataxó voices subvert traditional representations, transforming the understanding of space and culture. In this context, Anzaldúa's concept of the border is particularly pertinent, as it highlights that indigenous identities are fluid and are formed in liminal spaces, where traditions are intertwined with external pressures and new influences. Borders, far from being divisions, are transformed into spaces of creativity and resistance, allowing the Pataxó people to reaffirm their culture while dialoguing with the contemporary world. This dynamic of identity construction, highlighted by Anzaldúa, reflects the complexity of indigenous experiences in Brazil, highlighting the urgent need for an education that recognizes and values this multiplicity, creating an environment where decolonial narratives can thrive and manifest themselves. Thus, the practice of mapping not only reaffirms the Pataxó identity, but also paves the way for new forms of knowledge that are essential for understanding cultural interactions in an ever-changing world.

In short, this chapter proposes that the maps created by Pataxó students are more than educational tools; they are instruments of cultural resistance and identity affirmation. Through the intersection between intercultural education, southern epistemologies and cultural cartography, it seeks to emphasize the importance of recognizing and valuing indigenous knowledge as a fundamental part of building a more just and egalitarian future. In this sense, education should not be seen only as a means of transmitting knowledge, but as a space for struggle and affirmation of identities, where indigenous voices can be fully heard and respected.

The creation of the map by the students of the Xandó Village also presents itself as a powerful tool for correction and territorial claim, especially in the face of the distortions that platforms such as Google Maps and Google Earth present. Often, these systems point to sacred sites belonging to the Barra Velha de Monte Pascoal Indigenous Territory as belonging to the village next door, erasing the ancestral relationship and the belonging of the Pataxó people to that land. In addition, many of these place names are suggested by visitors, businessmen, and residents of the region, resulting in misappropriation and a narrative that reinforces the marginalization of indigenous peoples.

The project was developed from a participatory and collaborative approach, involving students, teachers and elders of the Pataxó community in the Xandó Village. The method was based on the orality and experiences of the students, who, under the guidance of educators, created a map that reflects their relationship with the territory. Cartography, in this context, is not only a technique of geographical representation, but a means of expressing and preserving the narratives and knowledge that shape the Pataxó identity.

The cartography process began with workshops on oral history and the symbolic value of the village's sacred sites, followed by hands-on mapping activities. These workshops were designed to stimulate dialogue between generations by allowing students to hear the stories told by the elders about the origin of the Pataxó people, their traditions, and the spiritual connection to the waters. These narratives were integrated into the map, which was built collectively by the students. This construction not only documents the territory, but also reaffirms the intrinsic connection of the Pataxó people with their land and their natural resources.

A powerful example within this narrative is the historic Rua do Telégrafo, which once connected Porto Seguro to Prado and remains deeply embedded in the Pataxó collective memory. More than a transport route, this path symbolizes a painful chapter in their history, marking the origins of the Xandó Village. In 1951, the cutting of telegraph wires led to the tragic "Fire of '51" massacre, a violent attempt to dismantle the community and suppress Pataxó identity. In response, the project’s cultural mapping methodology, inspired by Edson Krenak’s work with the Munduruku people, fosters memory and resistance. Mapping workshops at the Xandó Indigenous School empower students to express their perceptions of the territory, much like the Munduruku map their rivers and forests as cultural and spiritual landscapes. This practice not only preserves Pataxó histories but also reconstructs a collective narrative that challenges colonial distortions.

"The map is not just a trace on paper, it is the way to remember who we are and where we are. Every bend in the river, every tree, every hill is part of us. By mapping them, we reaffirm our presence and our history, resisting those who try to erase our existence and modify the way we see and relate to the land." (Krenak, 2020, p. 62)

The analysis of the results was carried out from direct observation and the analysis of interviews conducted with the participants, seeking to understand how the project influenced their perceptions about the territory and indigenous culture. The data collected revealed that, by actively engaging in the construction of the map, the students developed a more critical awareness of their cultural identity and their relationship with the land.

The project also stimulated discussions on sustainability and environmental preservation, themes intrinsically linked to the Pataxó culture. By dialoguing with ancestral knowledge about the relationship with land and water, students were able to realize the importance of defending their territories against external threats, such as economic exploitation and environmental degradation. This awareness is vital to strengthen not only cultural identity, but also the fight for territorial rights and the promotion of environmental justice. The recognition of Rua do Telégrafo and the 1951 massacre thus becomes an integral part of this struggle, as it refers to the need to remember and learn from the past to ensure a fairer and more sustainable future for the Pataxó people.

In this way, the project "Cartographing Histories and Cultures" not only fulfills an educational role, but also configures itself as an important mechanism of cultural resistance and reaffirmation of the Pataxó identity. Cartography, by incorporating the stories, knowledge and experiences of the people, becomes a tool of struggle, empowering new generations to claim their rights and celebrate their rich cultural heritage.

"Cartographing Histories and Cultures" illustrates in a striking way the importance of pedagogical practices that integrate traditional knowledge with innovative methodologies, standing out as a paradigmatic example of how education can function as a space of resistance and re-existence. The creation of a map that incorporates cultural and cosmological elements not only reaffirms the Pataxó identity, but also takes the form of an act of cultural and political resistance in a context marked by the marginalization of indigenous knowledge. This mapping, carried out by the students themselves, transcends the mere geographical record; it becomes an expression of belonging and a means of claiming spaces that have been historically appropriated by hegemonic narratives.

Conclusion

By valuing indigenous knowledge, the project challenges hegemonic narratives in formal education, not only critiquing their form but also questioning the essence of what constitutes knowledge, urging a reevaluation of prevailing epistemologies. Engaging with Boaventura de Sousa Santos' epistemologies of the South, it proposes an educational reconfiguration where ancestral knowledge is both respected and integrated as fundamental pillars of collective learning. The results highlight the urgency of merging traditional knowledge with decolonial pedagogical practices to create inclusive learning spaces that fully incorporate indigenous epistemologies. The "Mapping Histories and Cultures" project exemplifies this approach, enriching intercultural education and serving as a model for initiatives that celebrate cultural diversity and promote truly inclusive and sustainable education.

Additionally, by raising awareness of the Pataxó people's connection to their territory, the project strengthens the struggle for autonomy and land preservation in the face of ongoing threats. The creation of the map serves not only as an educational resource but also as a tool for mobilization and empowerment, fostering collective identities that resist time and oppression. Moreover, the project's decolonial approach underscores education’s transformative role, engaging students in critical reflections on identity and reality. By valuing and integrating indigenous histories and knowledge, it positions education as both a vehicle for social change and a field of resistance against narratives that seek to erase indigenous experiences.

Marcia Fernanda de Camargo is a Doctor in Science, Technology and Society from UFSCar with multidisciplinary education in Pedagogy and Visual Arts, including international business specialization, whose research focuses on decolonial issues, educational inequalities, and climate justice, emphasizing indigenous epistemologies and their intersections with affirmative action policies and sustainability.

Image: Marcia Camargo (2024)