We need a Better Framework for Measuring Inclusive Innovation Efforts

Alex Glennie, Adrian Johnston, and Robyn Klingler-Vidra propose a ‘types of capital’ framework to better measure inclusive innovation.

Trickle down innovation doesn’t work. As innovation hubs around the world gleam, there remains a persistent gap between those who benefit from advances in innovation and those in deprivation.

Take Northern Ireland (NI) as an example. Recent statistics show that 27.6% of NI’s working population is classified as economically inactive compared to the UK average of 22.2%. Additionally, the gap in life expectancy between Belfast and the rest of Northern Ireland is particularly pronounced in the areas of highest deprivation. The inequality gap continues to widen, with the preventable mortality rate in the most deprived areas now treble that in the least deprived areas.

To help address these challenges, the leaders of Belfast’s key institutions have formed a mission-based partnership – Innovation City Belfast (ICB). ICB exists to drive innovation, attract investment, and position Belfast as a globally relevant innovation landscape. A key priority for the partnership is to help innovation investments to deliver good jobs and positive socio-economic impact on the people of Belfast and the wider region. Providing people with the skills and confidence to participate in the innovation economy will not only stimulate economic growth but have a profound societal impact.

Inclusive innovation, which is defined as “the pursuit of innovation that has social and environmental aims, and local context, at its heart”, has proliferated as a framing device and aim in public policy. Inclusive innovation efforts seek to reduce inequalities and to orientate technology ‘for good.’ For example, the Philippines' Inclusive Innovation Industrial Strategy, launched in 2021, aims to address constraints faced by entrepreneurs when growing globally competitive businesses. UK Research and Innovation’s No Limits platform is another recent example; it aims to widen the pool of would-be entrepreneurs and innovators.

Despite growing awareness of the need to promote inclusion in innovation, there is still a lack of comprehensive methods for assessing the impact of these initiatives. And without clear evidence that they are delivering on their stated aims, there is a risk that interest and investment will fade, especially in the current geopolitical climate.

To deliver inclusion in innovation, we first need to establish better measurement.

First, we need to go beyond traditional ‘economic’ indicators of success, such as jobs created, or ideas patented. These indicators are important, but insufficient. We may learn how many jobs are created but know little about whether they are ‘good jobs’, and whether they are going to those who need them most. Patents demonstrate that new intellectual property is being created, but not by who, or whether these are ideas that will help or harm people and the planet. Second, we need to get better at measuring indicators of inclusion in real time, rather than waiting for outcomes which may happen years, if not decades, in the future. Having a theory of change is a valuable, and maybe even necessary, intellectual exercise when designing complex policy. But this alone often fails to specify sufficiently clear indicators of how outputs, outcomes, and impact should manifest.

We believe we have a way forward. A year ago, we embarked on a partnership to start addressing this challenge by creating a multi-dimensional framework to measure inclusive innovation. Building on our Inclusive Innovation book, we focused on a specific programme: the Stryve initiative, developed and implemented by Catalyst, a non-profit science and technology hub that works to drive innovation and entrepreneurship in Northern Ireland.

Funded by the International Fund for Ireland, Stryve is a programme that creates new pathways to employment for 16–24-year-olds who are furthest from participating in innovation-centric opportunities. The programme has delivered measurable impact, while building a robust foundation for scalable intervention to generate systemic change. To date, 80% of participants have gained accredited qualifications, with 53% progressing into employment and further education. In addition, entrepreneurial ambition among participants has risen from 31% to 86%. This is a new paradigm, building confident young people who are better equipped to progress to employment and training.

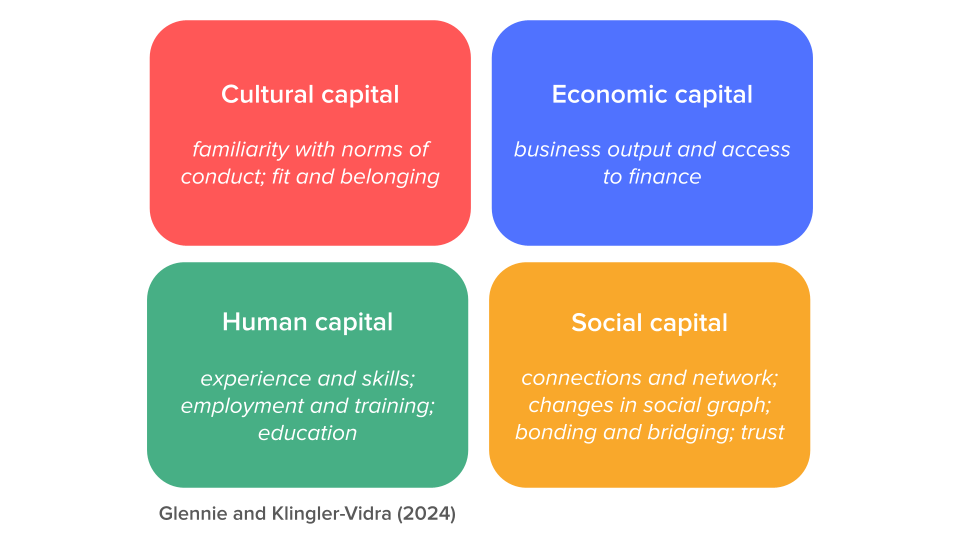

To understand the comprehensive impact of this programme, we needed to get beyond measuring a narrow set of economic indicators. We drew on social science’s great frameworks - from Becker to Bourdieu to Granovetter - to develop a framework with indicators across four types of “capital”: cultural, economic, human and social.

- Cultural capital is understood as familiarity with norms of conduct. The indicators in this heading measures changes in one’s feeling of fit and belonging.

- Economic capital covers the usual indicators measured with respect to innovation and entrepreneurship, such as business output and access to finance, to ensure alignment with existing methods.

- Human capital looks at indicators that assess experience and skills relevant for technology-centric innovation.

- Social capital has to do with measuring changes in social networks, to understand how strong and weak ties - and thus access to resources - evolves.

Our collaboration has also sought to engage a multi-stakeholder reference group to understand data gaps, and to consider the impact of inclusive innovation initiatives on a wider set of stakeholders (i.e., community and companies, as well as individual participants).

Getting inclusive innovation measurement right is not just an academic exercise; it’s an urgent imperative if innovation is to genuinely tackle societal inequalities rather than exacerbate them. We hope that our ‘types of capital’ framework represents a meaningful step toward capturing inclusive outcomes through cultural, economic, human, and social capital indicators. Crucially, we hope it offers enough flexibility so that it can be adapted to local contexts and specific initiatives elsewhere.

In Northern Ireland, our aim is to integrate this way of understanding and measuring inclusion into the remit and work of Innovation City Belfast and its partners, to address challenges like digital exclusion, poverty, health inequality and climate change, to ascertain how interventions affect access to economic opportunities and societal benefits.

We invite policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and communities alike to contact us to have a critical conversation about getting measurement right. We hope to be part of a wider set of efforts to advance a measurement framework that is sufficiently comprehensive and parsimonious so that we can learn more about how and when inclusive innovation initiatives can deliver lasting benefits for all.

Alex Glennie is an Affiliate of Glasgow Adam Smith Business School, Adrian Johnston is Innovation Commissioner for Innovation City Belfast, and Robyn Klingler-Vidra is Associate Professor of Political Economy and Entrepreneurship at King’s College London. Alex and Robyn are the authors of the book, Inclusive Innovation.

Photo by Pixabay