Northern Institutions Dominate International Development Research: So What?

Powerful arguments for why concerted action from governments and donor organisations to support locally-based researchers is essential.

The international community has long accepted that development needs to be locally owned, and that international support and cooperation need to facilitate leadership by local actors. Yet it is increasingly noticeable that development research is lagging behind in this respect. As we raise questions of access of researchers based in the Global South to the field of development, we also have to ask: what knowledge are development practices built on?

International development research, studying by and large the Global South, is dominated by scholars based in the Global North, far away from the realities they seek to understand. Without a thorough understanding of the local context, “helpful” policies and initiatives can have unintended – and possibly detrimental – consequences.

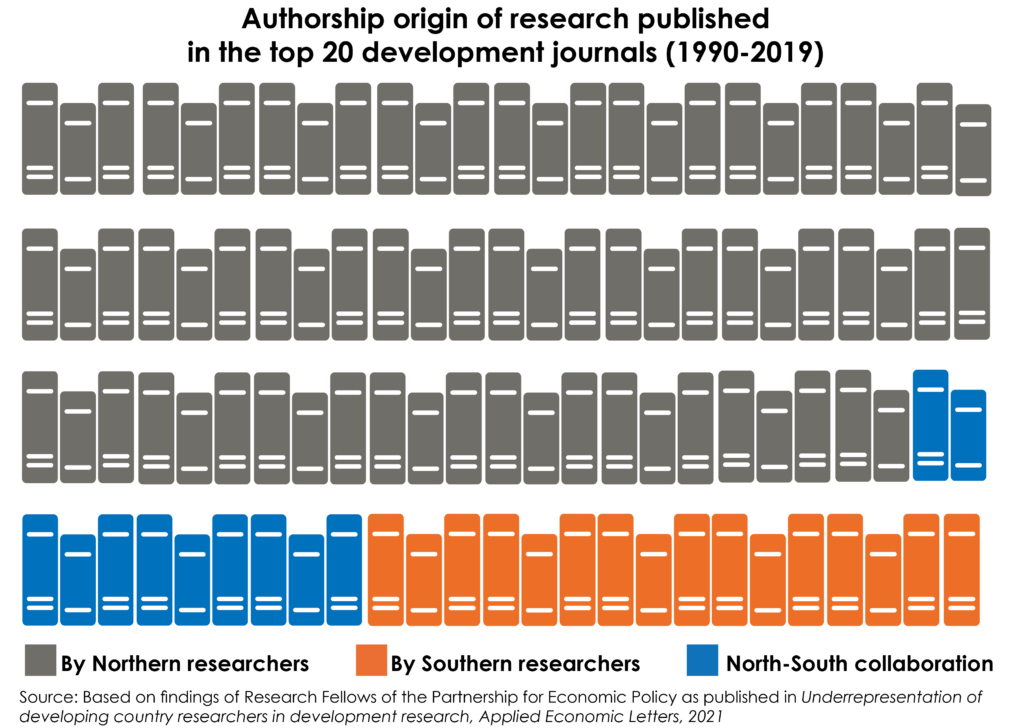

Publications in international development studies journals are overwhelmingly by scholars based in the Global North. Our analysis of top development journals revealed that researchers based in the South contributed to only just over a quarter of the publications. Northern scholars tend to publish in higher-ranked journals, are more often cited, and are over-represented in editorial teams. And there is no evidence of improvement in this bias, despite growth in collaborative publications: the prevalence of northern-based authors has increased in absolute terms. The number of researchers originating from the Global South working in policy institutions in the North may be increasing, but this “brain drain” helps perpetuate the dominance of Northern institutions.

A growing number of studies are demonstrating this continued marginalisation. In what is perhaps the largest data set on development studies, Martin Demeter shows that only 18 % of the publications in the 2010s were by Southern scholars. A small increase from the 1960s, when the figure was 13 %. Dani Rodrik recently highlighted how strong this bias is in economics, and others have demonstrated the same in research on global health and climate change. While the pandemic-imposed international travel restrictions might seem to be an opportunity to expand collaborations with local researchers, analysis of the AEA Registry of Randomized Control Trials showed no increase of Southern researchers leading these (and a worsening of the gender balance).

Southern-based researchers are not well represented in policy formulation either. Influential reports like the World Development Report and the Human Development Report include very few researchers from the Global South as authors, advisors, or editors. We found that only 12 % of significant contributors to the Human Development Report (1990-2020) were working in the Global South at the time of publication. For the World Development Report (1978-2020), the figure is less than 1%. Similarly, a compilation of readings on social protection published by the World Bank listed some 90 experts and authors, of which only four appeared to be based in the Global South.

But why is the geographic location of the author an issue? Why shouldn’t Northern donors predominantly work with and support development studies institutes in their own country, especially when access to resources for conducting quality research is limited in many countries in the Global South? Funders may look for what they consider the best evidence to inform their policies, or to support low-income countries. Northern research institutions also partner with Southern research institutions, and funders have encouraged this.

We believe that the balance needs to tilt towards opportunities for Southern-based researchers. First, there is an intrinsic reason: the need to ensure access to research based in the South, and make the field of development studies more representative, and thus contribute to decolonising the field.

Then there is the instrumental reason: local researchers know local context better and thus are more likely to carry out “valid” research, studies suited to a particular context, and are more likely to have a sustained positive impact on policies. Nathan Nunn provides examples from Indonesia and Zambia of how intimate local knowledge is needed to understand how interventions will work within or against local cultures and customs.

Concerted action from governments and donor organisations to support locally-based researchers is essential. Without it, the current power and influence structure will endure. In our analysis of participation in policy formulation, we found that Southern research systems provide few incentives to participate in policy debates, and little space for evidence use. Research training pays little attention to dissemination and communication. Difficulties in publishing research limit the visibility of researchers from the Global South, in turn reducing our opportunities to participate in local and international policy debates.

Given the very slow change in publication trends and policy processes, a big push is needed to make development research more representative. Based on findings from six studies led by Research Fellows of the Partnership for Economic Policy on the participation of researchers from the Global South in development, we are calling on the development research community to advocate for the changes we need to increase the participation of Southern researchers. We hope you will join in supporting funding for and recognition of local researchers, and promoting the journals and conferences that value the contributions of local expertise.

This post first appeared on From Poverty to Power.

Photo by Karolina Grabowska from Pexels