The Economic Challenges to the European Union of “Trumpism”

Nicholas Sowels reviews how President Trump overturned the world economic order since returning to office, with all this entails for the trade and future of the dollar. This text is part of a forthcoming e-book by the Global Governance Research Group of the UNA Europa network, entitled ‘The European Union in an Illiberal World’. [1]

The hostility displayed by President Trump towards the European Union (EU), including as an economic organisation, is longstanding. During his first term, he qualified the EU as “a foe on trade” (BBC 2018a). However, the second Trump administration (Trump II), which began in January 2025, has been far more assertive in seeking to change economic relations with the EU.

This chapter does not directly look at the political onslaught by Trump II against the liberal international order, or the internal politics of the EU, which deepen with each passing month.[1] Instead, it seeks to provide an overview of Trump II’s break with open trade and the multilateral system, while aiming to spread the burden of paying for US defence protection and the dollar as “global public goods”, including via dollar depreciation. The chapter ends by looking at the increasing monetary uncertainties and potential financial volatilities caused by Trump II and how these may undermine the global economy.

The Trump administration’s breaks with the multilateral trading system

The first Trump administration (Trump I, 2017-21) already implemented a series of protectionist policies, which broke with the free-trade tradition of the US Republican Party. For example, it imposed tariffs on products like steel and aluminium; it embarked on a trade war with China, beginning with $50 billion in tariffs on Chinese imports in March 2018, though the two countries signed a “phase one” economic and trade agreement in January 2020 (just before Covid); it renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), leading to the US-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA); and Trump I blocked reappointments to the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), making it inoperable (Lu & FASH455).[1] Concerning the EU, it triggered some tit-for-tat tariffs with the EU in 2020 over the perennial issue of EU subsidies to Airbus (ibid), having previously reached an agreement whereby the US would not put tariffs on cars, while European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker pledged the EU would import more soybeans and liquid natural gas (LNG) (BBC 2018b).

i) 2 April 2025: Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff shock

This piecemeal approach to undermining the multilateral trading system has given way to much broader actions by Trump II, most spectacularly on 2 April 2025 – Trump’s “Liberation Day” – when he brandished a chart of high “reciprocal tariffs” he intended to impose on US trade partners. Top of the list, although not with the highest tariff rates, were China and the EU. To the astonishment of most trade economists, the chart stated that the EU imposed a 39% tariff on US products, which his administration intended to counter with a 20% tariff. In contrast to the normal practice of evaluating tariffs as the percentage payment imposed when goods enter a country on an ad valorem basis, Trump’s figures calculated tariffs by dividing the deficit the US has with a country (exports less imports) by the sum of US imports from the country in question. For the EU, the US deficit (in 2024) was $235.571 billion, with US imports from the EU totalling $605.76 billion, yielding a supposed tariff rate of 38.8%, rounded to 39%. What Trump then called “polite reciprocity” meant US tariffs would be half this level, rounded to 20%. To justify its methodology, the administration claimed its calculations reflected the impact of non-tariff barriers on trade, like VAT (Jiménez 2025).

The ”Liberation Day” announcement was followed by months of economic and political drama. Immediately after his speech, the US stock market plunged, and there was also a sell-off of US government bonds, traditionally the safe-haven of investors across the planet (Inman and Jolly 2025). After a week, the ensuing panic pushed the White House to announce a 90-day pause for negotiations about the new tariffs to be imposed. This led to a sharp stock market rebound, but worries linger over US government bonds, see below (Arnold et al 2025).

ii) Trump’s tariff war with China and his deal with the EU

The most significant aspect of the “reciprocal” tariff announcement was the escalation of tariffs between China and the US. This began in early February 2025 but accelerated spectacularly, in a tit-for-tat process after Liberation Day, with the US raising its tariff on Chinese goods to 145% on 9 April, followed by China hiking its general tariff rate to 125%. While the US lowered its overall tariffs to 47% at the end of October, following the imposition of export controls by China on rare earths, which are essential to industries across the world, the trade war between the world’s two largest economies is far from resolved (Dunham 2025).

For the EU, a provisional end to trade negotiations with the US was reached in late July 2025, when it agreed to a 15% non-reciprocal, general tariff for most EU exports to the US, including cars, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors. This was accompanied by “Zero for zero” tariffs on several strategic sectors like aircraft (and components), certain chemicals and generics, semiconductor equipment, some agricultural products, natural resources and raw materials (Mateos y Lago 2025). While this tariff is far higher than before, the deal (which also includes EU commitments to buy American gas and make investments in the US) had the advantage of ending (provisionally?) the intense uncertainty over trade prospects for EU firms (ibid), although the deal has been criticised in Europe, as caving in to US pressure. This weakness of the EU has several causes, including: the poorer economic position of the EU today with respect to the US (and China); the difficulty of 27 countries pushing back collectively against such a large trade partner; and, notably, the dependency of the EU on the US in supporting Ukraine’s defence in the war against Russia (Swanson and Smialek, 2025).

iii) The broader picture and Trump’s attack on the principles of the World Trade Organisation

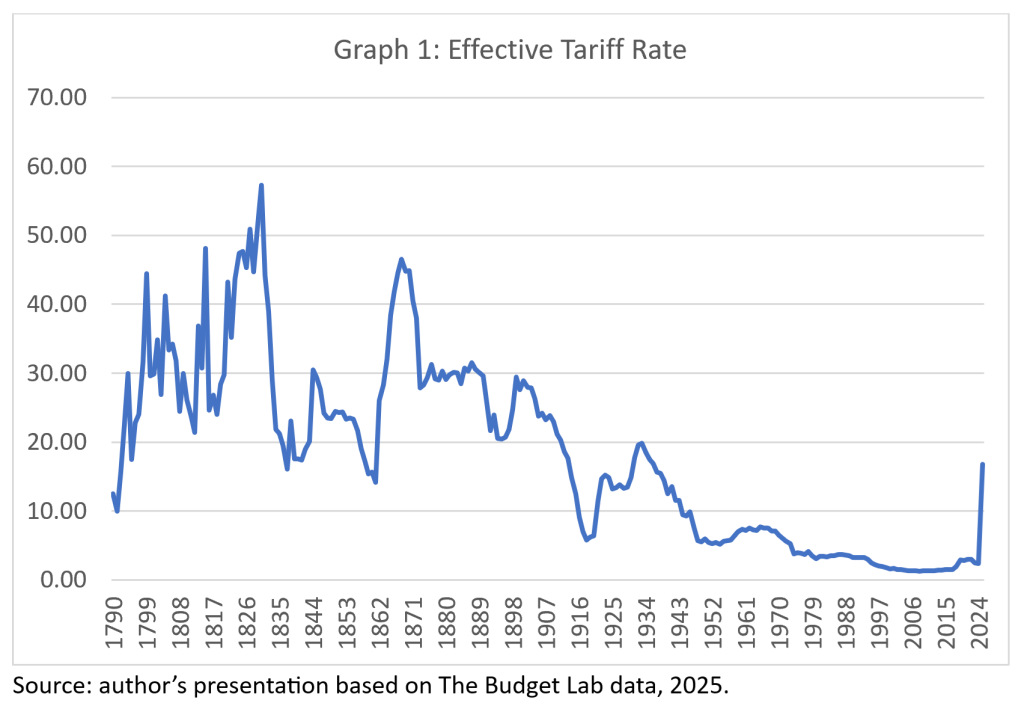

Looking at the broader picture, the Trump administration’s assault on the liberal international order in trade is hard to understate. Graph 1 displays historical data calculated by The Budget Lab (TBL) at Yale University (in early 2025) of the US’s “effective tariff rate”: i.e. the average import tariff weighted by the composition of imports. During the 19th century, the US industrialised behind trade barriers. By contrast, tariffs declined for most of the 20th century, especially after World War II. The impact of the Trump presidencies is thus striking: during Trump I, the effective tariff rate doubled from around 1.5% to nearly 3%. Yet this pales into insignificance with Trump II, when the average effective tariff rate rose from 2.4% at the start of 2025 to 16.8% at the end of November 2025: the OECD and others indicate 14% at year's end. It is truly in a new era.

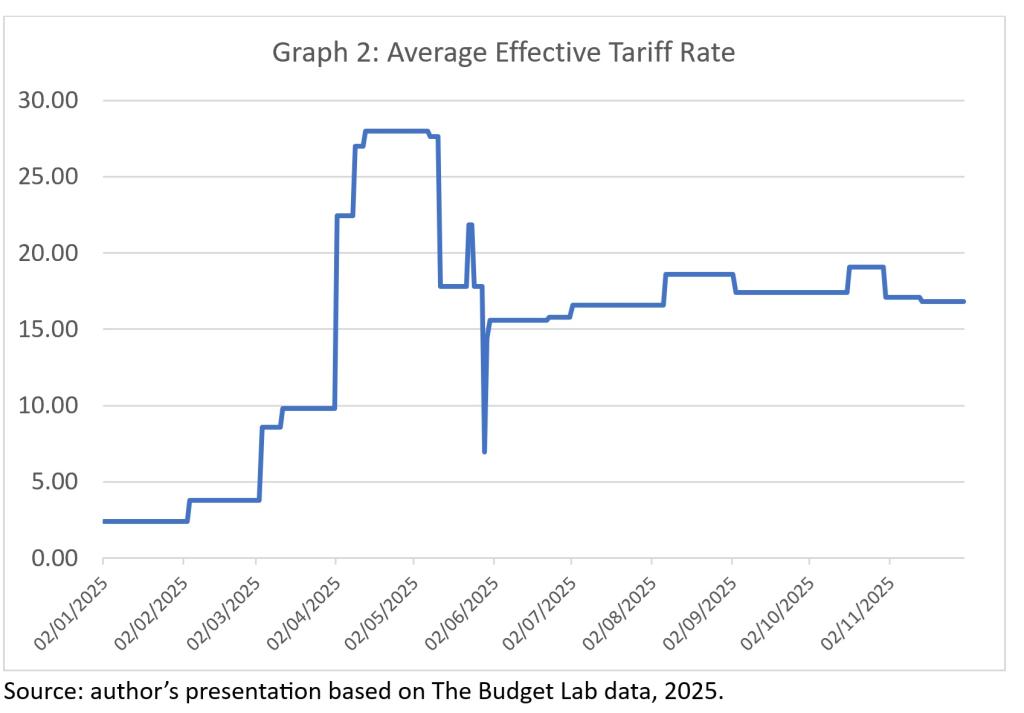

Moreover, as Graph 2 shows, there were wild gyrations throughout 2025, as tariffs were on-again-off-again in the months following Liberation Day. For leading trade economist and Nobel prize winner Paul Krugman, “the uncertainty, the constantly changing tariffs […seem] likely to have a chilling effect on business” (Wolf 2025). This holds not just for the US, but also its trade partners, and given the unpredictability of Trump’s behaviour, further changes cannot be ruled out: for example, if the Supreme Court invalidates Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977 to implement tariffs, and he has to resort to other means.

These tariff shocks have been aggravated by personalised actions that have undermined the US’s position in the international trading system. Instead of applying a blanket tariff on all imports, say of 10%, which would have been compatible with the principle of non-discrimination of the WTO, the Trump administration has acted unilaterally and arbitrarily. Aside from China, the 40% tariff hike on Brazil following the jailing of former President Jair Bolsonaro stands out as particularly capricious. Furthermore, the Trump family is using tariff policies for its own benefit. In late November 2025, a delegation of Swiss executives succeeded in bringing down US tariffs on Switzerland from 39% to 15%, after giving Trump “a specially engraved gold bar and a Rolex clock” (Ruehl 2025). Spectacularly, Vietnam got its “reciprocal tariff” reduced from 46% to 20% when its government provided land for the construction of a luxury golf course backed by the Trump family (Ratcliffe 2025).

The repositioning of the dollar in the global economy

Trump II is also having a significant impact on the dollar, with possibly major consequences for its role in the world economy and the global financial system. These factors could constitute big changes in how the liberal order has functioned since World War II, although the timeframe is likely to be considerably longer. A few factors at play are presented here.

i) The search for a weaker dollar

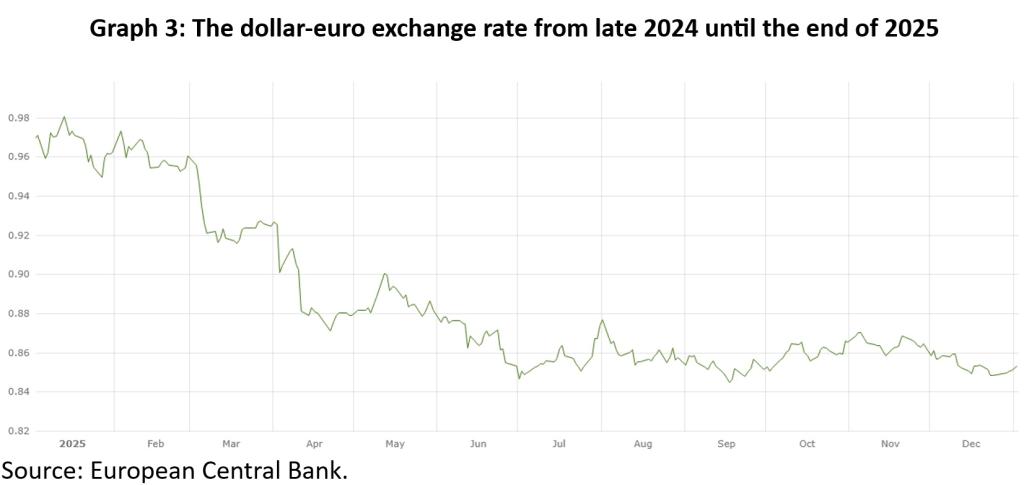

In the immediate wake of Liberation Day, the dollar fell as US financial markets dropped rapidly. Graph 4 shows the fall of the dollar from about €0.96 to €0.86 in the first half of 2025 (i.e. around 10%), before stabilising. For European exporters, this makes trading with the US (and countries with dollar pegs) even more difficult.

This fall in the dollar is paradoxical, although it does correspond to the aims of the Trump administration, which is pursuing an inherently contradictory policy of wanting a weaker dollar, but also wanting to ensure that the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency. Conventional economic theory suggests that tariffs, if trade partners do not retaliate, should lead to a dollar appreciation, as declining imports mean fewer dollars flow out of the US for purchases in foreign currencies. Moreover, if the US Federal Reserve maintains a tighter monetary policy to offset the inflationary effects of higher import prices, it should draw in foreign investment in dollar assets (Miran 2024, The Budget Lab, January 2025). Yet, the chaos surrounding Liberation Day produced the opposite effect, as global investors lost confidence in US markets, pushing down the dollar.

A weaker dollar, however, fits in with the Trump administration’s strategy, set out in late 2024, in a policy paper by Steven Miran (who first became Trump’s Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors in March 2025, before Trump appointed him to the Board of the Fed in September 2025). Miran’s paper states that “the deep unhappiness [of the US] with the prevailing economic order is rooted in persistent overvaluation of the dollar and asymmetric trade conditions”. Miran notably returns to the analysis of the Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, who, in the 1960s, argued that “the reserve asset producer must run persistent current account deficits as the flip side of exporting reserve assets” (Miran 2024, p 5). Miran goes on to argue that as the rest of the world grows relative to the US, pressures rise for the US current account deficit increase, and inflict ever-greater “pain” on US industries exposed to trade. “Eventually (in theory), a Triffin ‘tipping point’ is reached at which such deficits grow large enough to induce credit risk in the reserve asset” (ibid).

ii) Making others share the burden of global public goods

On 7 April 2025, during the chaotic week after Liberation Day, Stephen Miran gave a speech proposing ways that the US’s trade problems could be tackled. He began by asserting that the US had been providing the world with two “global public goods” (i.e. services provided freely to global society): i) a “security umbrella which has created the greatest era of peace mankind has ever known”, and ii) “the dollar and Treasury securities, reserve assets which make possible the global trading and financial system which has supported the greatest era of prosperity mankind has ever known” (Miran 2025). He acknowledged that while the international demand for dollar assets had held down US borrowing rates, it also “kept currency markets distorted” and severely punished US firms and workers. Moreover, he pointed out that foreign countries and financial institutions, especially China (the US’s “biggest adversary”) could buy US “assets to manipulate their own currency and keep their exports cheap” (Miran 2025).

To remedy this situation, Miran emphasised that “the best outcome is one in which America continues to create global peace and prosperity and remains the reserve provider, and other countries not only participate in reaping the benefits, but they also participate in bearing the costs”. Such burden sharing could take many forms, and other countries could: i) accept US tariffs without retaliating, to provide revenue for the US to finance these public goods; ii) they could stop unfair and harmful trading practices and buy more from America; iii) they could boost defence spending and procurement from the US, to help create American jobs; iv) they could invest and install factories in the US; or v) they could simply write cheques to the US Treasury to finance the global public goods (ibid).

More generally, Miran made the point that the conventional position of economists on free trade does not take into account the way in which the US trade deficit has not been self-correcting over the last five decades. In contrast to the orthodox theory that market disequilibria return to balance as prices change (in this case by currency devaluation), global trade is based on a structural imbalance (the US deficit) as the dollar has essentially remained an overvalued currency. This argument has been disputed: for example, renowned economic historian Barry Eichengreen places the responsibility for US deficits mainly on the mismatch between US savings and investment due to other factors (Eichengreen 2025). But, the issue of imbalances merits attention, especially as globalisation since the 1980s has relied much on US demand, with the US acting as the world’s “buyer of last resort”. Indeed, for left-wing economist Yanis Varoufakis, global growth has for long been based on a “global surplus recycling mechanism” (GSRM), whereby the US sucks in imports from the rest of the world, paid for by money the US can print, which other countries then send back to the US by acquiring in financial assets, real estate and non-strategic business. The winners of this “Dark Deal” are global elites in the US, and in China (as well as Germany etc.), while the losers are the immiserated workers across the globe (Varoufakis 2023, p145-56).

Arguably, a more cooperative and predictable effort by the US to address global trade imbalances could perhaps help (have helped) achieve burden-sharing with its partners, and possibly even a so-called “Mar-a-Lago accord”: a negotiated exchange rate realignment, and perhaps even an agreement between the US and foreign governments to reschedule payments on US bond held by foreign governments (Miran 2024). As it is, Trump’s hostility to former allies, his unpredictability, and above all his flouting of the law – at home and abroad – have made a mutually-beneficial negotiation all but impossible.

The new era of financial market volatility and monetary instability

Instead, the international community and global financial markets are trapped in a profound state of doubt and anxiety about future developments in Washington. To be sure, global growth has remained resilient: figures by the OECD in December 2025 project a slowdown in growth from 3.2% in 2025 to 2.9%. Similarly, it has been argued that after the turmoil of spring 2025, the dollar and the US have regained their status as a safe haven – at least for now (Kamin 2025). Yet, the OECD (among others) also points to numerous fragilities in the global economy, including: the risks of further tariff rises, export controls on rare earths, disappointing returns on AI investments and high asset values, highly leveraged non-bank financial intermediaries, interconnections between the latter and traditional finance, cryptocurrency volatility, etc. (OECD 2025, p. 11). There are also concerns about US public finances: the General government financial balance is forecast to remain at 7.5% in 2026, with debt reaching 125% (ibid, p277).

At the same time, the rising economic power of China, along with growing dissatisfaction across the world about the centrality of the dollar to global trade and the financial system are encouraging the search for alternative payment systems and stores of value. These multiple forces were reflected most visibly by surging gold (and silver) prices in 2025, as central banks and investors have been buying bullion: in September 2025, world gold stocks overtook the value of euros (McGeever), with a kind of remonetisation of gold taking place.

And yet, as widely noted, there is as yet no real alternative to the dollar as a global currency. In nominal dollar terms, the US is still the world’s largest economy, accounting for 26% of world GDP in 2025, compared to 16.5% for China, and 14.7% for the EU.[3] Its financial markets, and the all-important government bond market, are still far bigger and deeper than other markets, especially as European national debts remain fragmented, while China has not made the renminbi freely convertible. The dollar remains the only true “vehicle currency” for international trade, and it still accounts for nearly 60 per cent of foreign exchange reserves (Rogoff 2025, p. 4; Kamin 2025). Significantly, it was gold – and not euros – which became the second-largest reserve asset in mid-2025, as the dollar fell (McGeever 2025).

What the future holds for the dollar as the anchor of world trade and the global financial system is therefore uncertain. On the one hand, the US economy continues to show many strengths, in size, open access and in technological prowess. On the other hand, the Trump administration is not merely seeking better burden sharing in the provision of military protection and the dollar as two global public goods. Instead, it is smashing up the pillars of international law and multilateral institutions at breakneck speed, perhaps ushering in a period of global monetary instability. Numerous commentators (including Eichengreen) have pointed out that the world may be entering an age akin to the 1920s and 1930s, when the British pound was no longer the world’s reserve currency and the dollar had not yet become one. This argument draws on Charles Kindleberger’s seminal analysis of the Great Depression, which he argued was compounded by the way there was no hegemonic economic power capable of: “(a) maintaining a relatively open market for distress goods; (b) providing counter-cyclical long-term lending; and (c) discounting in crisis” (Kindleberger 1973, p 292). Of particular concern is the impact of a future financial crisis. The US authorities, notably the Federal Reserve, were key to preventing the global financial system from collapsing during the Global Financial Crisis (2007-2008) and the Covid pandemic (2020-2021). Trump’s disdain for multilateralism and his chaotic, partisan handling of the pandemic do not augur well for how his administration would react to a new financial crisis. Under Trump, the US – at best – would surely extract a high price for any effort to stabilise a crisis.

Conclusion

As 2025 has shown, Europe is not in a strong position to deal with US political and economic threats, in particular as long as it is dependent on US support for Ukraine. The EU’s lack of military power, its limited cohesion, poor public finances (especially in Italy and France, as well as in the United Kingdom), as well as its weak technological and economic performance compared to the US (and China) mean that it will at best be able to pursue a policy of damage limitation in an increasingly turbulent global economy. At worst, it will fall prey to what is already being called “The Scramble for Europe”, whereby the US, China and Russia carve up Europe in much the same way as Europe carved up Africa in the late 19th century (Rachman 2025).

Nicholas Sowels is a Senior Lecturer in English for economics at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University, where he also teaches political economy.

Photo by Pixabay

Footnotes

[1] Various generative AI tools were used for brainstorming, document location and proofreading in preparing this text. The words are all mine.

[2] For an excellent and detailed “Timeline of Trade Policy in the Trump Administration (2017-2021)”, see the webpage of FASH455 Global Apparel & Textile Trade and Sourcing, by Dr Sheng Lu at the University of Delaware, https://shenglufashion.com/timeline-of-trade-policy-in-the-trump-administration/

[3] The percentage shares of the US and China have been calculated using the Wikipedia entry, List of countries by GDP, based on data retrieved from the IMF in October 2025. The EU figure comes from Eurostat, News Articles, 26 March 2025: the links are respectively https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(nominal) and https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/wdn-20250326-1

References

Arnold, M., Duguid, K. and Grimes, C. (2025, 30 May) “Jamie Dimon warns US bond market will ‘crack’ under pressure from rising debt”, The Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/8c3628f3-477f-4124-8b3f-2bb76bf567cd

BBC (2018, 14 July) “Donald Trump: European Union is a foe on trade”, reporting on a CBS News story, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44837311

BBC (2018, 26 July) “Trump and EU’s Junker pull back from all-out trade war”, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44961560

Kindleberger, C. (1973) The World in Depression 1929-1939, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Dunham, R., (2025) “A complete chronology of the 2025 US-China trade tensions (updated)”, Global Business Journalism (GBJ), Tsinghua University, August, https://www.globalbusinessjournalism.com/post/a-complete-chronology-of-the-2025-u-s-china-trade-tensions

Eichengreen, B. (2025), ‘The global public good‘, in Gensler, G., Johnson, S., Panizza, U., and Weder di Mauro, B., (eds), The Economic Consequences of the Second Trump Administration: A Preliminary Assessment, CEPR Press, Paris & London. https://cepr.org/publications/books-and-reports/economic-consequences-second-trump-administration-preliminary

Inman P., Jolly, J. (2025, 9 April) “Dramatic sell-off of US government bonds as tariff war panic deepens”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/apr/09/dramatic-sell-off-of-us-government-bonds-as-tariff-war-panic-deepens

Jiménez, Miguel (2025) “Trump’s Big Lie: This is the simple formula he used to calculate the ‘reciprocal’ tariffs”, El País, 3 April, https://english.elpais.com/economy-and-business/2025-04-03/trumps-big-lie-this-is-the-simple-formula-he-used-to-calculate-the-reciprocal-tariffs.html

Kamin, S. B. (2025) "Dollar dominance and the Trump administration", VoxEU, CEPR, 1 October, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/dollar-dominance-and-trump-administration

Lu, Sheng “Timeline of Trade Policy in the Trump Administration (2017-2021)”, see the webpage of FASH455 Global Apparel & Textile Trade and Sourcing, by Dr Sheng Lu at the University of Delaware, https://shenglufashion.com/timeline-of-trade-policy-in-the-trump-administration/

Mateos y Lago, I., (2025) “EU-US trade deal: a damage limitation success”, Eco Flash, BNP Paribas, Economic Research, 28 July, https://economic-research.bnpparibas.com/html/en-US/EU-US-Trade-Deal-Damage-Limitation-Success-7/28/2025,51779

McGeever, J. (2025, 5 September) “Gold’s rise in central bank reserves appears unstoppable”, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/golds-rise-central-bank-reserves-appears-unstoppable-2025-09-04/

Miran, S. (2024, November) “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”, Hudson Bay Capital, https://www.hudsonbaycapital.com/documents/FG/hudsonbay/research/638199_A_Users_Guide_to_Restructuring_the_Global_Trading_System.pdf

Miran, S. (2025, 7 April) “Remarks” as CEA Chairman at a Hudson Institute Event, Briefings & Statements, the White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/04/cea-chairman-steve-miran-hudson-institute-event-remarks/

Rachman, G. (2025) “The scramble for Europe is just beginning”, The Financial Times, 17 November 2025

Ratcliffe, R. (2025, 11 August) “Farmers displaced by $1.5 billion Trump golf course reportedly being offered rich and cash”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/aug/11/farmers-displaced-trump-golf-course

Ruehl, M, (2025, 27 November) “Swiss politicians decry ‘gold bar diplomacy’ in Trump trade deal”, The Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/36c94522-78c8-4520-9efd-9e4800fd38d0

Swanson, A. and Smialek, J. (2025, 24 November) “Why Europe and the US Are Still Haggling on Trade”, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/24/business/eu-trade-trump-tariffs.html

The Budget Lab (TBL) at Yale University (2025, 31 January), “Tariffs, the Dollar and the Fed”, https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/tariffs-dollar-and-fed

The Budget Lab (TBL) at Yale University (2025, 17 November) “State of US Tariffs: November 17, 2025”, https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/state-us-tariffs-november-17-2025

White House Archives (2019) “Remarks by President Trump to the 74th Session of the United Nations General Assembly”, White House Archives, 25 September, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-74th-session-united-nations-general-assembly/

Varoufakis, Y. (2023) Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism, Vintage.

Wolf, M. (2025, 26 November) “The Wolf-Krugman Exchange: Trump’s ‘Vibecession’”, The Wolf-Krugman Exchange, Season 2, Financial Times video, https://www.ft.com/video/afccd9dd-9e66-441f-8af5-dad04ad73042?playlist-name=latest&playlist-offset=0