Decolonizing is the only option in 2025: Reflection Action of a Peace Educator

This is the ninth chapter in a forthcoming e-book, entitled 'Decolonial Education and Youth Aspirations'. Fatima Sajjad introduces a plan for less colonial ways of being and knowing in peace studies and international relations.

“O my body, make of me always a man who questions!” (Fanon, 1952)

A core function of education is to enable students to think critically about the present. And so I begin this chapter with a critical reflection on the present moment to explain the context of my current educational venture. I am a peace educator and researcher within the broader field of International Relations (IR). Examining structural, cultural and epistemic violence has been at the centre of what I do. I have been a vocal advocate of amplifying the voices of the racialized, marginalized and colonized communities in Peace Studies for many years prior to Oct 7, 2023. I initiated a research centre at my university named the Centre for Critical Peace Studies that aimed to question and undo the US/ Eurocentrism of peace and security studies (CCPS, 2021).

But all of this was in context of what we call the post 9/11 world and in a broader sense the post 1945 world. My work used to appeal to the ‘rules-based order’ that pretended to care about human rights and human life. That framework or pretension, within which I worked and argued for decolonizing Peace Studies, has been dismantled since Oct 7, 2023. For the past two years we have witnessed the unbelievable yet uninterrupted massacre of children in Gaza, every single day. We have seen unapologetic bombing of hospitals, residential areas, schools, universities, refugee camps, killing the injured, the doctors, paramedics, aid workers, journalists and refugees in unprecedented numbers (Mayer, 2025; Nadeem 2025). We see starving bodies of children and blood soaked bodies of parents killed by sniper shots while trying to reach aid. We continue to see the role of corporate media in normalizing this mass murder and the part of universities in penalizing protest against it (Guardian 2025; Takahashi 2024). We see complete impunity of Israel as it tears apart international law with full backing of United States’ veto and military power (Mann 2024, Callamard 2024). The world, as I saw it two years ago, has changed fundamentally or been exposed completely.

In 2025, if I argue for human rights, human life or decolonization, I do not know who I am talking to. I confront big questions this year. How do I teach peace amid fire? How do I make sense of this fire that does not cease to burn children every day? How do I teach peace when I witness unbelievable horrors, suffering, hunger, and thirst that no one is able to stop? How do I conceive of peace research amid massive and blatant violations of international law and suppression of truth? How do I conceive of peace research within epistemic hegemonies that sustain genocide (Albanese, 2024; Amnesty International, 2024; Human Rights Watch, 2024) and erasure by discrediting the voices of the oppressed and denying their lived experiences? What is credible knowledge in 2025? Or whose knowledge is credible in 2025? So, who do I talk to or make an appeal to for peace and dignity of human life? I am definitely not talking to the same old structures- the now unmasked colonial matrix of power that includes universities as institutions, top ranking academic journals, leading peace endowments and think tanks (we see their calculated ignorance on Gaza), big media houses, tech giants, social media giants, powerful people in governments and corporate sector and the state representatives (UN Report, 2025).

How can I make an appeal for peace and human dignity to this closely connected structure of power? They have lost credibility. Why should I make a case for inclusion of my voice to a body of knowledge I no longer consider credible? This is a chapter where I explore how I, as an academic of Critical Peace Studies and International Relations, attempt to find new ways to educate for peace and justice while the old ‘rules-based’ system seems incapable of addressing these very issues by drawing on decolonial scholarship. This includes the creation of two projects: The Pluriverse Lahore and the Journal of Critical Peace Studies.

I start by arguing that this year the site of credible knowledge has shifted. Credible knowledge no longer resides inside elite universities or high ranking journals or the mainstream media; a cursory examination of the social media discourses among communities protesting genocide indicate widespread mistrust of governments and their representatives. One of the most untrustworthy sources of information in 2024 were the White House press briefings on Gaza under the Biden administration, where we regularly saw government spokespersons’ inability to coherently respond to the questions they faced.

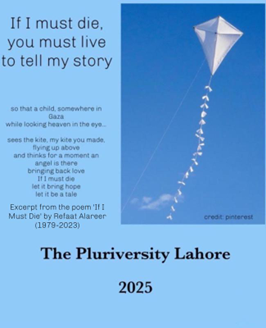

When I make an appeal for peaceful and just futures this year, my audiences have to be the people with credibility and integrity; they are the young people disrupting normalcy in universities around the world, the students in encampments, facing police raids as they shout #freepalestine, people marching on streets or campaigning on social media. Most importantly, my inspiration is the young Palestinian journalists busting dominant media narratives on Gaza as they report live from genocide while facing death, destruction and displacement. These are the people who can be trusted to build the futures we desire. For me, the future peace agenda must be written in Gaza. This is the place of credibility, dignity and unbelievable courage, as is exemplified by the countless stories from Gaza, health professionals like Hussam Abu Safia, Marwan Sultan, and Mahmoud Abu Nujaila; journalists like Bisan Owda, Wael Al-Dahdouh, and Motaz Azaiza; academics like Refaat Alareer and Mosab Abu Toha; grandfathers like Khaled Nabhan; and children like Hind Rajab and Ward al-Sheikh Khalil. This spirit within Gaza is unbeatable despite unthinkable suffering. Their bodies carry the weight of colonial oppression and genocide yet they refuse to obey or run away. They understand peace and justice better than anyone else.

When I make an appeal for peaceful and just futures this year, my audiences have to be the people with credibility and integrity; they are the young people disrupting normalcy in universities around the world, the students in encampments, facing police raids as they shout #freepalestine, people marching on streets or campaigning on social media. Most importantly, my inspiration is the young Palestinian journalists busting dominant media narratives on Gaza as they report live from genocide while facing death, destruction and displacement. These are the people who can be trusted to build the futures we desire. For me, the future peace agenda must be written in Gaza. This is the place of credibility, dignity and unbelievable courage, as is exemplified by the countless stories from Gaza, health professionals like Hussam Abu Safia, Marwan Sultan, and Mahmoud Abu Nujaila; journalists like Bisan Owda, Wael Al-Dahdouh, and Motaz Azaiza; academics like Refaat Alareer and Mosab Abu Toha; grandfathers like Khaled Nabhan; and children like Hind Rajab and Ward al-Sheikh Khalil. This spirit within Gaza is unbeatable despite unthinkable suffering. Their bodies carry the weight of colonial oppression and genocide yet they refuse to obey or run away. They understand peace and justice better than anyone else.

The era of the ‘New World Orders’ dished out from Washington is over. We can do without them. My audience for my work and advocacy (and my hope in 2025) is members of this young generation, Gen Z, as they lead the struggle to build better futures in one of the most traumatic times of recent history through encampments and marches.

Envisioning alternative futures remains at the core of my work as a critical scholar and peace educator. I believe the present moment demands a deeper reflection when we try to imagine our future. Let us first consider the present-day popular imagery of the future that almost always connects the future with high technology and little else. Popularized futuristic images have been imprinted on our minds for decades and they consistently show a high tech future as the only possibility. One obvious example of this kind of popular imagery is the Elon Musk version of the future that charts grand plans of high-tech lifestyles beyond planet earth. The problem with this one dimensional image of the future is a) it remains attached to the old rhetoric of modernity that hides its dark side ‘coloniality’ b) it maintains the old system of compartments where not everyone can access the modern hi tech compartment (Fanon, 1967).

Just one example of this compartmentalization is the smartphone industry that hides its connections with the cobalt mines of Congo where brutal child labor is a norm (Gross, 2023). The shiny picture of high-tech life is attached to modern day slavery, but this attachment continues to be a little dark secret not to be disclosed or discussed. The race, class, colonial compartmentalization of people continues as we leap forward to a technologically driven future. The seduction of technology shapes our aspirations for the future in the interest of the existing system. Capitalism thrives on our seduction as it promises to pull us up to this shiny place if we are obedient and work hard. Work hard, but in the name of dismantling the system of compartments, not for shifting compartments and leaving others behind.

Instead of envisioning the future through the rhetoric of modernity, we need visions that value life and justice for ALL, transparency and accountability for ALL, ethical and responsible production for ALL, ethical and responsible consumption for ALL. The future has to be for ALL, not for the selected few in the upper compartment.

This is what the project I am currently working on seeks to address. Keeping in view the bigger challenges we face in 2025, I am currently expanding the Centre for Critical Peace Studies network. We are working in three different but integrated areas: a) building a bigger community within and beyond universities; b) starting an educational channel and website called ‘The Pluriversity Lahore’ to reach out to young people beyond classrooms; c) and starting a new knowledge production forum, an innovative journal titled the ‘Journal of Critical Peace Studies’. I will explain later what makes this journal unconventional. An outline of our educational venture, built in context of Pakistan, is as follows.

The Pluriversity Lahore: A project of the Critical Peace Studies Society

The Pluriversity Lahore is a project of our expanded network of scholar-activists called the Critical Peace Studies Society (CPSS, 2021). Our work focuses on social justice, peace education, peace studies and international relations. We recognize that personal, political and global are interconnected. We examine self and international from the vantage point of the Global South and subaltern communities. This "international from below" approach directly confronts dominant, hegemonic worldviews, striving to reclaim and amplify the voices and agency of those historically marginalized (The Pluriversity Lahore Channel, 2024).

Our work begins with an acknowledgement that we are a part and a product of the modern/colonial system. While working within and through this system, we cannot claim to be creating a decolonial space; however, we can begin to move towards less colonial ways of being and knowing; that remains our effort.

To explain how we are trying to become less colonial through the Pluriversity space, in our context, let me first describe the local context. Coloniality works in different ways in the higher education landscape of Pakistan; the policies and structures represent neo-liberal frameworks that explicitly aim to produce human capital for economic growth. The captive mindset is rampant, as manifested in a constant desire to seek validation from the West (Alatas, 1972). And instrumental thinking is the norm as we see excessive emphasis on grade oriented, career oriented, and technology focused instruction. Universities tend to measure success through numbers and rankings. The ranking metrics set the goals of higher education (Sajjad, 2022). The domain of International Relations, and Peace and Security Studies, in Pakistan is largely dominated by state and security centric paradigms. Many local think tanks are closely aligned with state and security interests. A big part of local IR scholarship tends to revolve around a narrow range of security related topics. In this context, the Pluriversity project is striving to build a less colonial knowledge space by centering critical and independent scholarship. CPSS fosters a trans-disciplinary environment, inviting participation and contributions from scholars and activists across diverse fields who are committed to building a more just and peaceful world. The emphasis on decolonial, Southern, and subaltern discourses and practices underscores the project's commitment to shifting power dynamics in knowledge production. We call ourselves a ‘Rethink tank’, as we divest from the dominant knowledge of IR and Peace Studies.

We see ourselves as a project of combative Decoloniality, as defined by Nelson Maldonado-Torres (Maldonado-Torres, 2024). Radebe and Torres (2024) caution that while the rise of decolonial discourses in academia raises awareness of decolonization, it also risks diluting Decoloniality into a passive, non-combative field within the dominant liberal knowledge paradigm. They critique the modern Westernized University as a “white academic field that suppresses resistance" (Radebe and Torres, p. 296), emphasizing that decolonization must reject liberal and neo-liberal knowledge frameworks upheld by these institutions. Hence, The Pluriversity Lahore moves beyond the confines of a university. We shift the site of knowledge production as an act of combative de-coloniality.

The Pluriversity Lahore is a locally rooted, globally connected, multilingual educational website and channel that offers a learning space that accepts and respects multiple sources of knowledge (The Pluriversity Lahore, 2024). This space offers indigenous research courses, critical reading circles, rich reading and art resources, guest lectures, a Gen Z research corner, dialogues on epistemic justice / futures of education and a lot more. These diverse offerings are all geared toward addressing the multifaceted pain caused by systemic, structural, cultural, and direct violence in the contemporary world. Through this forum, we challenge the dominant knowledge of International Relations.

We are also offering a self-paced, free open access course titled ‘I and IR: An Introduction to the Critical, Decolonial, and Reflexive International Relations’. We received an overwhelming response to our registration call, with over a hundred students and faculty members from various regions of Pakistan enrolling within just a week. We connect with this larger community through email, zoom and WhatsApp. Since the concepts we teach (epistemic hegemony, coloniality, intellectual imperialism, captive mind) resonate with everyday experiences of our participants, many of them remain eager to learn more. We ask them to write back to us and share how they experience coloniality in their life, and we learn more from their stories. Also, we are making a critical intervention in standard IR courses like ‘International Relations since 1945’. Centering Gaza, we are offering a course that examines IR since Oct 7, 2023. We collectively reflect on the collapse of the post-World War II rules based order at the current moment and imagine different possibilities of alternative futures. The course is titled ‘IR since 2023: A Reconstruction’. Through these open courses we are actively building knowledge and language that defies the dominant narratives of IR, constructed by the powerful. The channel provides us a wider reach and a leverage to impact popular discourses. Our aim is mainstreaming the critical, to undo captive minds and instrumental neo-liberal thinking. We believe that if more people become critically conscious, it becomes difficult for powerful people to manipulate information and manufacture consent.

Along with these IR related courses; we also plan to engage in wider debates on higher education policies and the purpose of education, with other disciplinary domains, with artists, activists and policy makers. We aim to question prevailing neo-liberal frameworks and introduce Autonomous knowledge frames as advocated by Alatas (2006). We believe in the transformative impact of consistent dialogue, reflection and action. The Pluriversity’s mission is to become a significant and impactful learning space that fosters critical thinking, promotes diverse perspectives, and empowers individuals to become agents of change.

Journal of Critical Peace Studies (JCPS):

A key area of our critical intervention in educational space is the mechanism of contemporary knowledge production and dissemination. Our special focus is on the highly profitable academic publication industry. We aim to launch an unconventional academic journal that centers the voices, perspectives and lived experiences of the Global South and the racialized, marginalized, colonized communities around the world, in Peace Studies/International Relations and related domains.

The Journal of Critical Peace Studies (JCPS) embraces a very broad definition of peace. Peace is viewed as a process and a struggle towards mitigating direct, structural, cultural as well as epistemic violence. We view epistemic violence as a key constituent of structural and cultural violence; hence it remains our main area of focus.

What makes us unconventional?

We are a knowledge production forum operating as an open channel. We intend to offer an open writing and thinking forum that demystifies the process of knowledge production by holding live discussions of authors with peers/reviewers at multiple stages of research. Our focus is on the process instead of the finished product of knowledge making. In the age of generative AI, valuing the process is important. Through live discussions on research ideas and their progress, we aim to build an open forum for co-constructing knowledge rooted in lived human experiences. The live peer reviews will not only transform the typically opaque review process into public conversations, they will also accelerate this process, which is crucial in our current times of rapid change and multiple challenges. Additionally, they will help us foster a more collaborative approach to knowledge creation. By allowing authors to upload and discuss multiple drafts, JCPS acknowledges that knowledge is not static but evolves over time through ongoing inquiry and dialogue.

Another way in which we challenge the dominant knowledge is by changing the content of knowledge. At its core, JCPS centers the perspectives of the marginalized– those whose knowledge has historically been excluded or dismissed by mainstream academia. This focus on "insights from the ground" allows JCPS to rewrite Peace Studies and International Relations "from below," challenging hegemonic narratives and offering alternative frameworks for understanding peace. As mentioned earlier, our work will be guided by the Autonomous Knowledge frameworks (Alatas, 2022; 2024). Autonomous knowledge independently identifies problems without being dominated by other traditions; it formulates its own concepts, and methods. It is open to external influences; it evaluates ideas based on merit rather than cultural or national origins.

JCPS plans to extend beyond the published articles, seeking a diverse range of contributions from religious scholars, journalists, creative artists, and policymakers. This inclusive approach recognizes that valuable insights can come from diverse sources and that building a more just world requires the participation of many. JCPS offers a platform for these individuals to connect and share their work. The journal also offers research internships for students, fostering the next generation of critical scholars. JCPS is currently run by dedicated scholars and students on a voluntary basis; the initiative is exploring innovative funding models for financial sustainability. One such approach is affiliate marketing of local, ethical brands. This not only provides a potential revenue stream but also promotes ethical consumption among young people, contributing to a broader shift in consumer behavior. JCPS also seeks funding from local and global organizations that align with its values. Ultimately, JCPS envisions building an alternative ecosystem – encompassing educational spaces, community engagement, and ethical businesses – that actively divests from the colonial matrix of power and its continued pursuit of profit over people and planet.

Fatima Sajjad is the founder of ‘The Pluriversity Lahore’- a multilingual educational forum based in Pakistan that divests from the dominant knowledge of peace and security. She is the Founding Director of the Centre for Critical Peace Studies and Associate Professor at University of Management & Technology Lahore. LinkedIn: Fatima Sajjad

Image: created by Fatima Sajjad, including excerpt from the poem ‘If I Must Die’ by Refaat Alareer