Community-led Solutions to a Global Housing Crisis

Community-led provision of homes can counteract the increasing commodification of housing. It offers a solution to our crisis but requires a global perspective to understand, link and facilitate existing examples that can be implemented across the world. During Habitat III I met with the Building and Social Housing Foundation (BSHF) and urbaMonde, two organisations that are pioneering this approach.

The need for a global perspective

At Habitat III there has been a lack of representation and contribution from UK national and local governments, which is a serious concern. I have listened to mayors passionately addressing the issues outlined in the New Urban Agenda (NUA), including neighbouring European countries such as Germany. The UK’s absence demonstrates a parochial mentality to a housing crisis that it shares with the world.

Sadiq Khan, the new mayor of London, has a huge crisis to deal with: houses are unaffordable, speculation is rife, the working poor are being forced to the outskirts whilst the centre is becoming a Notopia of empty luxury flats owned by foreign property investors. These issues are not unique to London; they are a global epidemic caused by free market property provision.

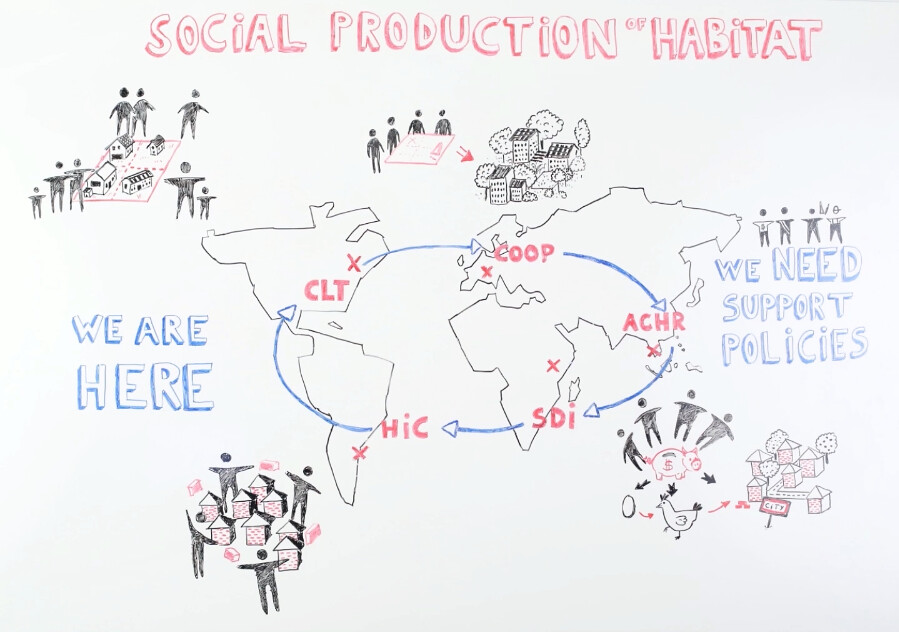

Figure 1, Social Production of Habitat Platform, copyright: urbamonde.org

Previous government-led, mass provision of housing suffered from a different set of issues associated with the modernist approach that saw a house as a ‘machine for living in’, alongside segregation of communities. There is a need to re-think how homes can be provided that isn’t government or developer-led.

‘Community-led housing’ is an umbrella term that describes a situation where people take control of providing their houses. Some examples of this exist in the UK but it is more prevalent in other countries. There is a wealth of existing experience that can provide demonstrable solutions.

An example in the global North are the ‘building groups’ in Berlin that now provide one in ten of all new homes. However, in Uruguay 25% of housing is owned by co-operatives (David Ireland, BSHF) and in India “out of a total stock of 170 million houses, 120 million are created by people” (Kirtee Shah, ACHR).

Although both of these Southern examples exist because of a lack of government-provided homes, that is equally their strength in demonstrating the ability of people to provide for themselves. If properly acknowledged and supported by government, community provision need not represent precariousness or lack of quality but instead empowerment.

“We often see the transfer of ideas having to be from the North to the South, but I think actually, the way in which people have got on with it in places where there isn’t infrastructure offers a lot that we could learn from countries like Ecuador.”

David Ireland, BSHF

Inspiring and organising the ‘social production of habitat’

During separate events at Habitat III, BSHF (World Habitat Awards) and urbaMonde (Social Production of Habitat Award) both presented awards to community-led housing groups. They use this as a platform to create global recognition of innovative projects that are transferable solutions to housing. Their network of projects facilitates peer-to-peer learning, bringing together groups from around the world.

UrbaMonde specifically focus on community-led housing projects and in 2014 embarked on the ‘Social Production of Habitat’ platform. It’s aim is to unite groups from around the world through regional ‘Hub Meetings’ and a ‘Digital Social Platform’ that is both a database for publicity and research, and enables online interaction between groups. Through this initiative they hope to bridge the North-South divide, integrate with public support actors, create peer-to-peer financial solidarity and link with the Right to the City platform. Their approach is further explained in this promotional video.

The community-led home

When a person provides their own home, they are directed by a set of human values; the housing unit is not simply number for political persuasion, or a house to be sold - it is home to live their life within based on principles such as comfort, durability, sustainability, wellbeing, adaptability and aesthetics.

A participatory process enables collective control over the design. Future residents can react to changing social dynamics. Traditional housing design has changed little, yet the notion of a nuclear family or separate place of work is out-dated in many parts of the world. Additionally, the process of providing homes as resident-groups that will live in the same area creates lasting social cohesion.

Community-led developments usually aim to provide homes in the most affordable way possible. This is often more efficient than the trickle-down, money-wasting bureaucracy of government provided homes. It offers a more direct form of government spending and support.

For the world to solve its housing crisis, there must be government acknowledgement and support for community-led housing. The work of BSHF and urbaMonde can create the structure that brings together the spectrum of possibilities to realise the scale of provision that is possible. Community Land Trusts, Co-operatives and Self-Help Housing are just some of the models that can be further explored.

UK specific reading: ‘Scaling the Citizen Sector’

Rowan Riley (@RowanRiley_) is currently in the final year of a Master’s in Architecture, with experience of professional housing design at HaworthTompkins in Central London. Throughout the conference Rowan will be focusing on alternative forms of housing provision and social inclusion for those who live within. To keep up to date with the GLI team’s commentaries and policy pieces from HABITAT III, or for outputs by GLI teams at other international events please see here.

Photo credit: scjody via Foter.com / CC BY-SA

Photo credits: Figure 1, urbamonde.org