Assessing the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation: Platform Responses to Information Disorders

Madalina Botan and Minna Aslama Horowitz argue that verifiable, and inclusive oversight is essential if the EU is to match the scale and urgency of today’s information disorders. This is a chapter in a forthcoming e-book by the Global Governance Research Group of the UNA Europa network, entitled ‘The European Union in an Illiberal World’.

Over the past twenty years, digital transformation has profoundly reshaped our information ecosystems, shifting control from traditional journalism to a handful of dominant online platforms. As the influential policy report by the Council of Europe (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017) illustrates, this shift has given rise to diverse and widespread information disorders, encompassing both the unintentional and deliberate viral spread of false information online, as well as the intentional distortion of facts to target specific individuals, groups, or institutions. The report categorizes these disorders as mis-, dis-, and malinformation, respectively: misinformation refers to the unintentional dissemination of false information, disinformation to the deliberate creation and sharing of falsehoods, and malinformation to the intentional distortion of truthful content to cause harm.

As a substantial body of research indicates (e.g., Mansell et al., 2025), online information disorders significantly distort the public discourse on pressing global challenges such as climate change, armed conflicts, and migration. Simultaneously, the platforms that constitute the primary arenas for the spread of false and misleading content initially positioned themselves not as media organizations but as intermediaries, thereby evading editorial responsibility. This stance had posed a significant governance challenge both nationally and internationally.

Numerous countries have enacted so-called disinformation laws; however, in many instances, these are used more to suppress dissent than to foster trustworthy information environments (e.g., Lim & Bradshaw, 2023). Member states of the European Union (EU) have sought to address disinformation through a mixture of national and supranational approaches. Legal responses remain limited and contentious due to concerns regarding freedom of expression. Consequently, non-legal strategies—such as policy guidance and international collaboration—are more prevalent. Despite increasing awareness of the complexity of disinformation, only a few countries—typically those most vulnerable to foreign information threats—have developed robust national strategies, leaving much of the structural regulation to the EU level (Bleyer-Simon, 2025).

Indeed, for nearly a decade, the EU has taken a proactive approach in implementing various measures to curtail disinformation and safeguard democratic processes, including the development of regulatory frameworks that require online platforms to assume a degree of accountability for information disorders. In 2018, it led the creation and adoption of the Code of Practice on Disinformation (CoPD), a self-regulatory instrument designed for technology companies, the online advertising sector, and fact-checking organizations. The CoPD was reinforced in 2022 and further revised in 2024 (see, e.g., European Commission, 2025a), evolving into a co-regulatory tool under the Digital Services Act (DSA) as of 2025.

The DSA is a cornerstone EU regulation that addresses a wide array of risks and harms associated with digital platforms, including illegal content, targeted advertising, and online abuse. It also seeks to make platforms’ terms and conditions more accessible and transparent, while ensuring that content moderation processes are contestable by users. The DSA places particular responsibilities on so-called Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs)—defined as services with more than 45 million users in the EU—including Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Bing, TikTok, YouTube, and Google Search.

Yet even as the EU expands its regulatory architecture through the recently launched European Democracy Shield (EDS) (European Commission, 2025), a structural challenge persists: platforms continue to control the data, design, and visibility of precisely the interventions intended to counter information threats, creating an accountability gap between regulatory ambition and operational reality.

Transparency of the Code

The Code of Practice on Disinformation (CoPD) encompasses a wide range of commitments. These include measures to demonetize disinformation, prevent advertising systems from being exploited for the dissemination of false or misleading content, ensure transparency in political advertising and media, promote digital literacy, empower users, collaborate with fact-checkers, and strengthen platform-wide policies to address both misinformation and disinformation. Under the CoPD, platforms are required to submit detailed accounts of their related actions—known as transparency reports—twice a year.

A recent monitoring initiative by the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO) provides an evidence-based benchmark for assessing how well platforms comply with the Code and the effectiveness of their actions. EDMO’s evaluation of transparency reports covering the period from January to June 2024 (Botan & Meyer, 2025) analyzes the quality and completeness of the information submitted by Meta (Instagram and Facebook), Google (Search and YouTube), Microsoft (LinkedIn and Bing), and TikTok.

The assessment evaluates whether the platforms have provided sufficient documentation, transparency, and relevant qualitative and quantitative data, and whether the reported activities are verifiable and can be corroborated by external sources. Specifically, the analysis focuses on: how platforms support users in identifying disinformation and in broader literacy capabilities regarding information disorders (CoPD Commitments 17 and 21); how platforms support researchers, particularly in terms of data access (Commitments 26, 27, and 28); and how platforms collaborate with fact-checkers, including access to relevant information (Commitments 30, 31, and 32). The key findings of EDMO’s assessment are summarized below.

Do platforms support users?

Media and information literacy is widely recognized as a key component in strengthening societal resilience to disinformation and forms a central pillar of the EU’s strategic approach. However, EDMO’s assessment of platform activities reveals that, although all major services claim to support media literacy, their efforts remain largely unaccountable, lacking transparency, and are inconsistent in both scope and quality.

Platforms frequently promote branded campaigns—such as Microsoft’s collaboration with NewsGuard, a commercial tool for tracking disinformation—and various educational resources. Yet they rarely disclose data on user reach, engagement, or learning outcomes. Reporting at the national level is the exception rather than the norm. There are also notable disparities in how media literacy is implemented across platforms. TikTok, Meta, and Google provide relatively well-documented tools, whereas Microsoft offers little in the way of detailed descriptions. Moreover, partnerships established to produce literacy content are often described vaguely, and the involvement of external experts or evaluation mechanisms remains limited. It appears that platforms tend to outsource literacy campaigns to third parties, while contributing little themselves to content development or the visibility of these initiatives.

All seven platforms analyzed also claim to offer tools designed to help users identify disinformation. However, their implementation reveals substantial shortcomings in transparency, impact evaluation, and user effectiveness. The most structured interventions were reported by Google, which included fact-check panels beneath videos and algorithmic changes aimed at reducing the spread of harmful content. Meta flagged misleading posts on Facebook, applied false information overlays, and introduced warning labels on Instagram. TikTok offered less detail regarding the transparency of its fact-checking labels or the mechanisms by which users are redirected to credible sources. Microsoft provided minimal information about its AI-driven tools—developed to detect fake accounts and limit bot-driven disinformation—including how these tools are integrated into its platforms or whether they are evaluated for impact.

Do platforms support research?

Despite being a core commitment of the Code of Practice on Disinformation (CoPD), empowering the research community through access to non-personal, anonymized data remains poorly implemented across all seven platforms. TikTok’s Research Application Programming Interface (API) provides the most consistent support; however, the criteria for data access are not clearly defined, limiting opportunities for independent verification. Google (through its Jigsaw research initiatives) and Microsoft (via open-source AI research) offer access to selected datasets through dedicated research programs. Nonetheless, overall accessibility to disinformation-related data remains severely restricted.

The assessment finds that platform data access policies are vague and partnerships appear selective, with little evidence of fair or independent allocation mechanisms. Although some platforms report supporting research efforts, they offer limited detail regarding the scope, consistency, or inclusiveness of these initiatives across the broader research community. Meta exemplifies this limited approach. The company offers access through a partnership with the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan, allowing researchers to share specific datasets under controlled conditions.

However, Meta’s decision to discontinue CrowdTangle has significantly hampered research efforts, raising concerns over transparency in tracking disinformation trends. CrowdTangle was a widely used public insights tool that enabled users—journalists, researchers, and civil society organizations—to monitor and analyze the spread of public content on Facebook and Instagram. It offered valuable insights into viral content, misinformation, and user engagement patterns, making it a vital instrument for understanding digital information flows and assessing platform accountability. In 2024, Meta replaced it with the Meta Content Library and Content Library API. However, unlike its predecessor, access to these new tools is restricted to a select group of academic and nonprofit researchers through a complex, formal application process administered by ICPSR.

The implementation of governance frameworks for access to sensitive data is among the weakest and least transparent aspects of platform conduct. While platforms frequently reference pilot programs and collaborations, these are rarely accompanied by concrete information regarding implementation, researcher participation, or outcomes. No platform has yet articulated a governance model that would enable independent oversight of data-sharing practices. Reviewers also noted that platforms tend to provide only high-level summaries of governance processes, with little or no detail on enforcement or evaluation mechanisms.

One documented case in Meta’s transparency report involves a partnership with CASD (Centre d’Accès Sécurisé aux Données), a French-based secure infrastructure providing access to anonymized data for scientific research, under strict safeguards. In the context of the DSA and the CoPD, CASD participated in a pilot project. The assessment verified that a small group of researchers was engaged in this pilot to validate the end-to-end access process, from initial application to actual data retrieval. However, no confirmation has been provided regarding the continuation of the pilot or progress in establishing an Independent Intermediary Body to assess and approve future data access requests.

Another example is Google’s collaboration with the European Media and Information Fund (EMIF), a grant-making initiative launched in 2021. While this initiative has been positively received within the context of the CoPD, multiple stakeholders have argued that such funding mechanisms are no substitute for meaningful data access and platform accountability. Furthermore, Google’s management of resources under EMIF lacks transparency and clear procedures for awarding grants based on scientific merit.

The European Democracy Shield (European Commission, 2025) reinforces these findings. It underscores the lack of timely, granular, and verifiable data from platforms as a systemic risk to democracies. The proposal for standardizing data sharing and protocols, coordinated through national hubs and an EU-level crisis response mechanism, aligns with this study’s conclusion that data currently provided by platforms via (non-) existing data sharing governance are insufficient for independent evaluations.

Do platforms support fact-checking?

Fact-checking is a critical pillar of the Code of Practice on Disinformation (CoPD), yet the transparency and effectiveness of platform support for fact-checking vary considerably. An analysis of the four main platforms’ engagement with fact-checkers reveals a fragmented and largely opaque landscape.

While most platforms refer to partnerships with fact-checking organizations, few provide convincing evidence of structured or systematic cooperation. Google offers its Fact Check Explorer tool and publishes some information about its fact-checking activities. Meta reports an established collaboration with the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN). TikTok claims to have existing partnerships and an interest in expanding them, yet offers limited disclosures regarding funding, geographic coverage, or the long-term sustainability of these efforts. Microsoft, meanwhile, lists no formal fact-checking partnerships. It notes a collaboration with NewsGuard—a commercial service monitoring disinformation—and refers to AI-driven fact-checking initiatives without clarifying how these are implemented, assessed, or aligned with its CoPD commitments.

Across the board, the platforms analyzed fail to demonstrate the real-world effectiveness of their fact-checking collaborations. Reporting often lacks clear information about partner organizations, and provides little data on user engagement, content reach, or measurable outcomes. While some basic details—such as partner names and coverage by Member State—are included, essential elements remain missing or poorly documented. These include disclosures about the organizations involved, the allocation of financial resources, review methodologies, compensation structures, and verifiable indicators of impact.

The CoPD not only calls for collaboration with fact-checkers but also requires platforms to provide them with meaningful access to information and to incorporate their findings into platform operations. EDMO’s analysis finds that, across all platforms, performance in these areas is consistently weak. Tools for long-term monitoring of misinformation are either absent or inadequately developed, and there is little evidence that platforms share substantive performance data with the fact-checking community.

Furthermore, the evaluation highlights inconsistencies in how platforms assess the impact of fact-checking, with minimal attention given to contextual and country-specific insights. Evidence and verification processes are also lacking—supporting research is rarely made available for public scrutiny, and mechanisms for verifying claims remain underdeveloped. Overall, improvements are needed in methodology, data transparency, and verification procedures in order to strengthen the credibility and impact of independent fact-checking.

The EDS (European Commission, 2025) further validates some of the concerns expressed in this study by explicitly acknowledging that voluntary arrangements under the CoPD have not ensured meaningful platform accountability. The EDS identifies “persistent opacity” and “insufficient cooperation with independent verification actors” as structural weaknesses in the current governance model. It calls for formalized, enforceable cooperation frameworks, especially during periods of high informational risks, and implicitly confirms that the EU itself recognizes the limits of symbolic co-regulation.

Conclusions: the opaqueness of platform measures and the need for more accountability

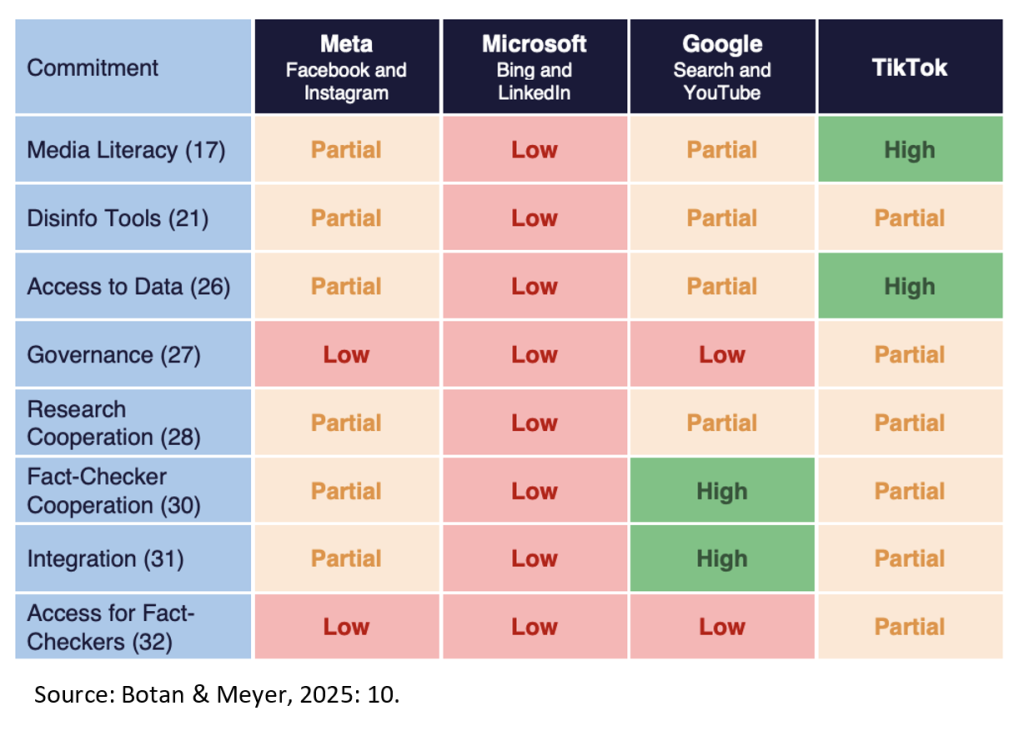

Overall, EDMO’s report reveals persistent shortcomings in transparency, independent oversight, and impact evaluation across all commitments that were included in the analysis. As a result, the current implementation of the Code appears fragmented and performative (see the overview in Table 1). Comparative compliance across all commitments raises concerns about its capacity to deliver substantive improvements in limiting the spread of disinformation.

Table 1: Overview of VLOP and VLOSE Compliance Assessment with CoPD Commitments

While some surface-level compliance and isolated initiatives are evident, the lack of systemic transparency, meaningful independent oversight, and sustained collaboration with the academic and fact-checking communities indicates that the platforms’ real commitments often fall short of the Code’s intended impact. Multiple tools, actions, and partnerships were deemed partially compliant, primarily because Member State-specific or other granular data were unavailable for independent verification.

The report further demonstrates that verifying the content of transparency reports proved challenging. Access to public data that could corroborate reported activities was limited, making independent validation difficult. Indeed, the key barrier remains the lack of transparent processes for granting access to relevant data. There is little publicly available information on how researchers can request data or what kinds of datasets are accessible for disinformation research. This opacity hinders the ability of academic institutions and independent experts to investigate disinformation dynamics, raising concerns among both researchers and fact-checkers about the overall transparency of online information flows.

These shortcomings are particularly alarming given the ongoing challenge of online information disorders and the evolving regulatory obligations that platforms now face. According to a 2023 survey, 53% of EU citizens reported encountering disinformation “very often or often in the past seven days”. In the same survey, the most frequently cited threat to democracy was “false and/or misleading information circulating online and offline” (Eurobarometer, 2023). This underscores the importance of platform measures to counter information disorders, especially in a context where, on the one hand, US-based platforms are scaling back anti-disinformation efforts under the banner of “freedom of speech” (e.g., Kaplan, 2025). On the other hand, Chinese-owned TikTok—considered a national security concern in several countries (e.g., Yang, 2024)—has become a prominent source of news for Europeans, despite being one of the hardest platforms on which to detect disinformation (Newman, 2024).

In response to such challenges, the EU has integrated the voluntary CoPD into the DSA framework (European Commission, 2025a), thereby transforming it into a co-regulatory benchmark of the Code of Conduct on Disinformation (CoCD) as of July 2025. Under the DSA, VLOPs and VLOSEs are now expected to align with its commitments as part of their legal obligations. Additionally, Article 40 of the DSA, which explicitly addresses data access for researchers, was also formally adopted by the European Commission in July 2025.

Given the findings in EDMO’s assessment, the transition to a Code of Conduct under the DSA should be accompanied by significantly more vigorous enforcement of CoPD commitments. Without more robust accountability mechanisms, the implementation risks becoming largely symbolic—fulfilling compliance in appearance rather than in substance—while the fundamental problems of disinformation and platform accountability persist.

The recent Democracy Shield suggests that the EU is already moving toward addressing these structural shortcomings. Its introduction of mandatory incident reporting and real-time access to platforms’ data represents a shift from voluntary transparency to legally enforceable cooperation. Fact-checkers, media literacy experts and researchers are explicitly referenced as part of the “democratic resilience infrastructure,” indicating a potential repositioning – from peripheral contractors for verification tasks to recognized, formalized partners in detecting and responding to informational crises. Whether these mechanisms will be implemented at the necessary scale is still uncertain, but they at least signal an acknowledgement of the very gaps documented in this study.

In this context, strengthening efforts to build a more trustworthy information environment becomes urgent, not only for European citizens but as a global example of effective democratic governance. The new CoPD reporting requirements, mandated under the DSA, represent a significant opportunity to improve transparency and accountability. Platforms must now provide more detailed reports outlining how they moderate content and manage political advertising. This will enable researchers, regulators, and the public to gain a better understanding of platform operations (Borz et al., 2024). Such openness could support earlier detection of disinformation trends and more consistent enforcement of regulatory standards (Nenadić, 2019).

Ultimately, mechanisms such as the CoPD/CoCD and the associated reporting obligations are vital tools for ensuring reliable information ecosystems that support international cooperation, democratic resilience, and human rights. This study illustrates how independent monitoring can support and reinforce the EU’s regulatory ambitions by ensuring that platform actions go beyond symbolic compliance. Sustained, verifiable, and inclusive oversight is essential if platform transparency and accountability are to match the scale and urgency of today’s information disorders.

Madalina Botan, National University of Political Science and Public Administration, Bucharest/ EDMO Hub BROD (madalina.botan@comunicare.ro), is a senior researcher and Associate Professor at the National University of Political Studies and Public Administration. Her work focuses on electoral studies, algorithmic propaganda, and policymaking, with current research on online disinformation and EU regulations, including the Code of Conduct on Disinformation and the Digital Services Act. She is a member of the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO). Prof. Botan has published extensively on media effects and political communication. She is the co-author of the EDMO report, "Implementing the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation" (Botan & Meyer, 2025).

Minna Aslama Horowitz, University of Helsinki/DECA Research Consortium/EDMO Hub NORDIS (minna.aslama@helsinki.fi), is a Docent at the University of Helsinki, a Nordic Observatory for Digital Media and Information Disorder (NORDIS) researcher, and a Fellow at the Media and Journalism Research Center (Estonia/Spain) and St. John’s University, New York. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on epistemic rights and European media policy, particularly those related to public service and media and information literacy.

Photo by Markus Winkler

References

Bleyer-Simon, Konrad. 2025 (ed). How is disinformation addressed in the member states of the European Union? – 27 country cases. European Digital Media Observatory. https://edmo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/EDMO-Report_How-is-disinformation-addressed-in-the-member-states-of-the-European-Union_27-country-cases.pdf

Botan, Madalina & Trisha Meyer. 2025. Implementing the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation: An Evaluation of VLOPSE Compliance and Effectiveness (Jan–Jun 2024). European Digital Media Observatory. https://edmo.eu/publications/implementing-the-eu-code-of-practice-on-disinformation-an-evaluation-of-vlopse-compliance-and-effectiveness-jan-jun-2024/

Borz, Gabriela, Fabrizio De Francesco, Thomas L. Montgomerie, and Michael Peter Bellis. 2024. “The EU Soft Regulation of Digital Campaigning: Regulatory Effectiveness through Platform Compliance to the Code of Practice on Disinformation.” Policy Studies 45 (5): 709–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2024.2302448

Eurobarometer. 2023. Democracy. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2966

Eurobarometer. 2024. European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/european-declaration-digital-rights-and-principles.

Eurobarometer. 2025a. The Code of Conduct on Disinformation. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/code-conduct-disinformation.

Eurobarometer. 2025a. European Democracy Shield. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/14587-European-Democracy-Shield_en

European Commission. (2025, November 10). European Democracy Shield: Proposal for strengthening the EU’s resilience against digital threats. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_2660

Kaplan, Joel. 2025. "More Speech and Fewer Mistakes." Meta Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news/2025/01/meta-more-speech-fewer-mistakes/.

Lim, Gabrielle, and Samantha Bradshaw. 2023. Chilling Legislation: Tracking the Impact of “Fake News” Laws on Press Freedom Internationally. https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/chilling-legislation/.

Mansell, Robin et al. 2025. Information Ecosystem and Troubled Democracy. A Global Synthesis of the State of Knowledge on News Media, AI and Data Governance. Observatory on Information and Democracy. https://observatory.informationdemocracy.org/report/information-ecosystem-and-troubled-democracy/

Newman, Nic. 2024. Overview and Key Findings of the 2024 Digital News Report. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2024/dnr-executive-summary.

Nenadić, Iva. 2019. "Unpacking the 'European Approach' to Tackling Challenges of Disinformation and Political Manipulation." Internet Policy Review 8 (4): 1–22.

Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakshan. 2017. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Council of Europe.https://edoc.coe.int/en/media/7495-information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-research-and-policy-making.html

Yang, Lihuan. 2024. "National Threats and Responses Toward Digital Social Media: The Case of Global TikTok Regulations." SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4912211 .