Chinese Development Finance: A Convergence of Passions and Interests

Kevin P. Gallagher's commentary for the Emerging Global Governance (EGG) series explores China's growing passion for green finance, south-south development cooperation, and global leadership.

The world of development finance is seeing the rise of key new actors. In just over a decade China’s two national policy banks, China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, that operate globally have emerged as global leaders in development finance in general and in financing for energy projects in developing country governments in particular. Moving forward, China has founded or co-founded two new multi-lateral development banks (MDBs) and at least 13 regional and bilateral funds that will increase Chinese development finance abroad by orders of magnitude. China’s expansion is motivated by a number of factors, not the least of which is an excess of national savings and trillions of dollars of dollar reserves that China seeks to diversify across the globe. Through development financing abroad, China not only is able to diversify its savings globally in a strategic manner that steers finance toward building globally competitive Chinese firms, gaining access to global markets, and building global alliances. China initially attempted to increase the capital of Western-backed international financial institutions, but the West would not fully commit, so China resorted to building its own institutions. And as Jin Liqun, the new head of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank recently said, "Now that China has developed, it is our turn to contribute"—China is emerging as a leader in providing global public goods.

China’s expansion is motivated by a number of factors, not the least of which is an excess of national savings and trillions of dollars of dollar reserves that China seeks to diversify across the globe. Through development financing abroad, China not only is able to diversify its savings globally in a strategic manner that steers finance toward building globally competitive Chinese firms, gaining access to global markets, and building global alliances. China initially attempted to increase the capital of Western-backed international financial institutions, but the West would not fully commit, so China resorted to building its own institutions. And as Jin Liqun, the new head of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank recently said, "Now that China has developed, it is our turn to contribute"—China is emerging as a leader in providing global public goods.

Such a stepwise increase in global development finance arrives just in time, as the world faces major infrastructure and energy gaps and has just committed to increasing finance for sustainable development on a global scale through the Sustainable Development Goals and at the G-20. That said, China’s portfolio of overseas energy finance is heavily concentrated in fossil fuel operations that accentuate climate change, especially in coal. China’s development finance model, nonetheless, is such that Chinese development financial institutions could make a swift and more decisive shift toward cleaner energy finance for all. China’s model currently matches excess savings and reserves with national oil, gas and coal firms. It could easily use the same model to globalize its world-class solar and wind industries.

Complementarity & risk

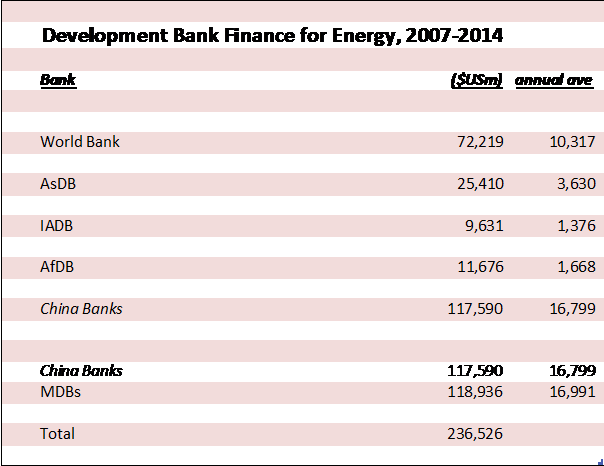

A Working Paper written with Yongzhong Wang of the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Science and colleagues Rohini Kamal from Boston University and Yanning Chen at Johns Hopkins University, we estimated the extent to which China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China provide financing to foreign governments for energy projects. In that paper we estimate that China’s national policy banks already lend as much to foreign governments for energy as all the major Western-backed MDBs combined—the World Bank, European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, African Development Bank, and the Asian Development Bank.

Source: Gallagher et al (2016), Fueling Growth and Financing Risk: The benefits and risks of China’s development finance in the global energy sector, Boston University Global Economic Governance Initiative, Working Paper 05-16.

Between 2007 and 2014 Chinese banks doubled the amount of energy financing available to national governments, adding another $117.5 billion dollars in energy finance for foreign governments. Not only did Chinese finance increase the total amount of finance; Chinese banks are financing energy projects all over the world and expanding the set of countries that receive energy financing as well. In other words, Chinese energy finance does not compete with the set of countries and energy sectors that are currently being financed by Western-backed MDBs, but rather complements them.

We also find, however, that Chinese energy finance is exposed to significant country and macroeconomic risk. In contrast with the Western-backed development banks across the world, the Chinese policy banks are engaged with countries with higher country risk ratings and in commodity-backed loans that are at risk of stress given the fall in commodity prices and associated macroeconomic downturns in the developing world.

Moreover, Chinese policy banks are heavily exposed to climate and social risk. China’s energy loans are highly concentrated in fossil fuel extraction and power generation, especially coal. Indeed, Chinese banks have provided upwards of $28 billion in financing for global coal projects—projects that accentuate climate change and social risks. Investing in coal poses risks to Chinese financial institutions and to society. In terms of China’s bottom line, there is a growing consensus that many coal plants will be decommissioned over the next decades due to climate change and air pollution regulations. What is more, coal plants are increasingly controversial at the community level, and community conflicts can lead to plant closings as well. There is therefore an increasing likelihood that some Chinese coal assets will become stranded assets.

Coal also poses significant health and climate risks as well in terms of localized air pollution from sulfur emissions and global climate change from carbon emissions from coal power plants. Using conservative estimates of the climate and local health costs of coal plant emissions, we calculate that the yearly social cost of Chinese overseas coal-fired power plants amounts to $29.7 billion. Assuming a power plant lifetime of 30 years, total social cost could range from $117 billion to $892 billion.

The aforementioned realities thus raise the stakes for, and importance of, China’s new interest in green finance. China has made the boldest national commitments in terms of reducing financing and incentives for coal and fossil fuels on the mainland under the US-China climate agreement and is poised to globalize those national policies.

Forecast & recommendations

As commodity prices fall and the macroeconomic outlook for many of China’s borrowers declines, China will need to diversify its global energy portfolio. To meet these goals Chinese overseas development finance will need to make a significant change in the composition of its lending portfolio. Such a shift will not only help China’s banks mitigate the significant risks associated with the current portfolio of its policy banks, it will also enable China to meet its broader global commitments.

Through the newly minted Sustainable Development Goals and again at the Paris Climate Summit of 2015 world leaders—China included— have committed to steer public finance toward energy and infrastructure in a manner that is environmentally sustainable and socially inclusive. Also in 2015, the governments of the United States and China committed to “controlling public investment flowing in projects with high pollution and carbon emissions both domestically and internationally.” In 2016 China dubbed ‘green finance’ a global commitment under the Group of Twenty nations (G-20) with the establishment of G-20 study groups in both green finance and climate finance.

China is poised to lead

With regard to international governance, China is also driving the creation of new supportive arrangements, such as the South-South Climate Fund to help mitigate climate change and the South-South Cooperation Fund to help advance the Sustainable Development Goals.

To strengthen complimentarity with the Chinese financing and new governance initiatives, Western-backed MDBs will need to coordinate across a variety of banks and climate and development cooperation funds, in a number of countries and international institutions in order to ‘blend’ financial instruments to make climate friendly investments more financially viable. This is difficult as it is, and it is an open question whether the new administration in the U.S. will continue to support such efforts at all.

In contrast, China’s banks have the advantages of being able to combine non-concessional, concessional, and grant financing under one ‘roof’ at their policy banks, and thus blend financial instruments more efficiently. They do not face many of the institutional and political constraints that the Western-backed institutions do. What is more, China now has world class solar and wind industries.

China now increasingly has the ‘passion’ for green finance, for south-south development cooperation, and is exhibiting global leadership such as through its G-20 commitments and new development banks. What is more, China’s passions are increasingly aligned with its ‘interests’ in terms of gaining market share for its highly competitive solar and wind industries.

Kevin P. Gallagher is Professor of Global Development Policy at Boston University’s Pardee School of Global Studies, where he co-directs the Global Economic Governance Initiative (GEGI). His latest books are The China Triangle: Latin America’s China Boom and the Fate of the Washington Consensus (Oxford University Press, 2016) and Ruling Capital: Emerging Markets and the Reregulation of Cross-Border Finance (Cornell University Press, 2015). Follow him on twitter @KevinPGallagher To find out more about the EGG project, please click here.