Europe’s Strategic Weakness, Institutional Limits, and the East-West Fault Line

Eduard Vasilj argues that the European Union’s capacity to act as a strategic power is constrained not only by institutional weaknesses, limited military independence, and the absence of a unified foreign and economic policy. Most critically, it is hindered by persistent East-West disparities.

The EU is a major economic actor with a GDP of around €18 trillion and 450 million inhabitants. However, these internal divisions threaten its cohesion and global influence. Unless the East–West fault line is addressed, the Union remains vulnerable. External actors continue to exploit these weaknesses.

Despite its complex institutions, the EU lacks a central core of state power. Key decisions in the Common Foreign and Security Policy must be adopted unanimously by the Council, as stipulated in the EU treaties, granting each member state an effective veto. Unlike state systems with majority voting, there are no procedures to overrule blocking states or exclude them. Formal expulsion from the EU is not legally provided for.

Article 7 sanctions only address serious breaches of fundamental values - democracy, rule of law, human rights - and cannot resolve foreign or security policy deadlocks. Even in extreme cases, sanctions are limited to suspending Council voting rights.

History and Institutions of the EU

The EU emerged after WWII to secure peace, stability, and economic cooperation. It began with the European Coal and Steel Community (1951) and the Treaties of Rome (1957). Over the decades, it developed from economic cooperation into a political union with shared institutions, a single market, a common currency, and limited foreign policy coordination. Yet, it remains a supranational construct lacking the tools of sovereign state power.

The European Commission initiates legislation, monitors implementation, manages the budget, and represents the EU internationally. The European Parliament and Council share legislative power; the European Council sets policy guidelines without enforceable authority. The European Court of Justice ensures the uniform application of EU law, and the European Central Bank independently manages the Eurozone's monetary policy. This separation balances common and national interests but does not replace military strength or foreign policy autonomy.

Unanimity in Council decisions allows one state to block action, as seen in Hungary’s 2025 veto of Ukraine support and Slovakia's delay of Russia sanctions. The EU remains reliant on NATO and the US for defence, despite several members being major military powers and arms exporters.

Economic and institutional differences are accompanied by political and psychological discrepancies.

Since 2004, the EU has expanded eastward, encompassing Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia (as of 2013). Despite this, the Union remains economically and politically unbalanced.

Eastern European states often play only symbolic roles in negotiations, as seen in the Ukraine peace talks, where Germany, France (and the UK) along with Polandas the sole Eastern European representative effectively conducted the talks. This reinforces the perception that other countries in the region have limited influence in EU decision-making and are primarily regarded as markets and sources of labour.

The Economic Divide Between Eastern and Western Europe

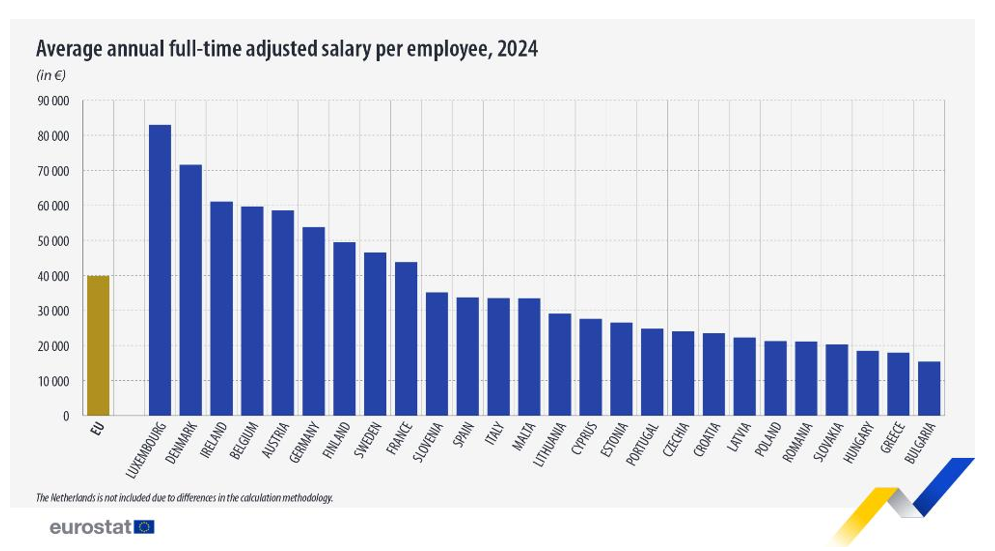

The economic gap is stark: Bulgaria’s GDP per capita was 66% of the EU average in 2024, Luxembourg’s 241%. Western EU members earned €45,584 annually on average, Eastern EU members €22,021, and the EU average €39,800.

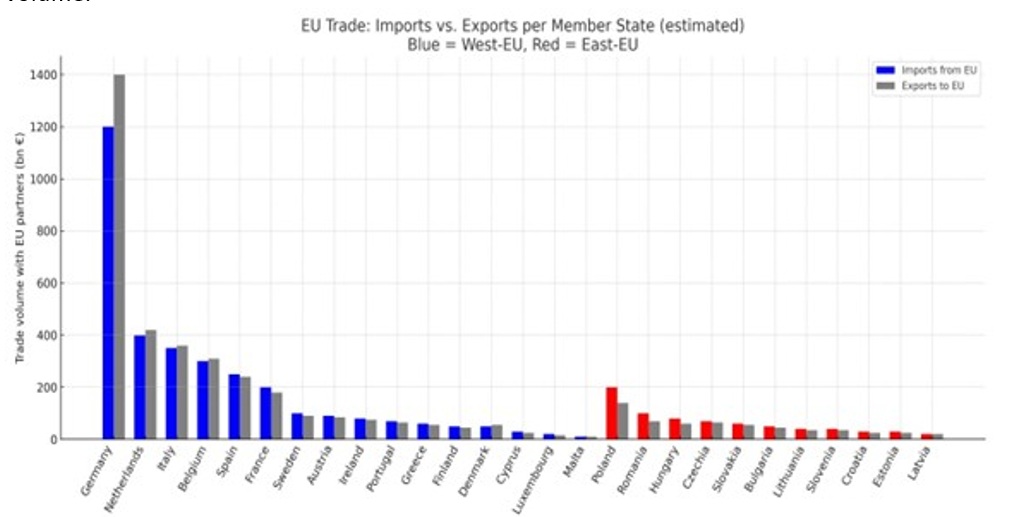

Intra-EU trade reflects Western dominance: Germany (~€1.4 trillion), the Netherlands (<€400 billion), Italy (~€350 billion), and Belgium (~€300 billion). Eastern states: Poland (~€200 billion), Romania (~€150 billion), Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia (€50–100 billion). The smaller Eastern and Southeastern European states, such as Bulgaria, Lithuania, Slovenia, Croatia, Estonia, and Latvia, have volumes below €50 billion. It is noteworthy that no Eastern European EU member exports more within the Union than it imports; all these countries thus have a negative trade balance with other EU member states. This imbalance underscores the economic dominance of the Western member states in intra-EU trade and demonstrates that, despite EU integration, Eastern European states contribute only a fraction of the total trade volume.

Massive internal migration followed: 1990–2015 saw 4.4 million leave the Western Balkans; Bulgaria experienced a population decline of ~22%. Without migration or automation, Eastern working-age populations could shrink another 10% by 2035. Western Europe hosts ~348.2 million people, Eastern Europe ~101.4 million - a demographic imbalance that, if this trend continues, will increasingly depopulate the Union from East to West.

Political Consequences and Tensions within the EU and Potential Accession Candidates

The recent presidential election in Romania increasingly revealed the frustration of segments of the population in Eastern European member states. Although Romanian intelligence determined that candidate Călin Georgescu received indirect support from pro-Russian networks, encompassing coordinated social media activities and campaign financing whose origins could not be fully traced, it must be noted that a large majority of the Romanian population voted for him. On December 6, the Romanian Constitutional Court declared the election invalid due to serious irregularities.

In this context, it is also worth mentioning that in Hungary and Slovakia, the governments of Orbán and Fico, respectively, secured their majorities in part through strong anti-EU narratives.

The EU accession candidates Montenegro and Moldova also exhibit particular vulnerabilities in their political processes, as well as strong societal currents opposed to EU membership. In 2022, there were reports of Russian interference in elections in Montenegro, and in 2025 in Moldova. Despite this interference, it must be noted that at least a significant portion of the population opposes integration into the EU.

Conclusion

Internal economic, political, and institutional differences threaten EU stability and strategic capacity. Without bridging the East-West divide, a common foreign and economic policy, military independence, and institutional strengthening, the EU cannot act as an independent strategic power. Article 7 safeguards fundamental values, but without an exclusion mechanism, the Union remains fragmented, economically divided, politically paralyzed, and incapable of forming a cohesive global power bloc comparable to the US or China.

Eduard Vasilj holds degrees in Political Science and International Law from Goethe University Frankfurt and in Political Science and Organization from the University of Zagreb. With nearly 20 years of senior executive experience in multinational corporations across Europe, he advises governments, sovereign investors, and corporations on geoeconomic and geopolitical risk, governance, and strategy. His research includes the Gulf region, providing actionable guidance at the intersection of strategy, security, and economic policy.

Photo by Konstantin Mishchenko