Science Diplomacy can save the Amazon

Gustavo Macedo and Andrea Garcia call on scientists and transnational organisations to mobilize their networks to discover opportunities, exchange ideas and invite governments and representatives from the private sector to the table.

September started with an attack against world Science. The Brazilian government just announced additional cuts to federal scholarships for research. So far in 2019, 17,424 grants were cut, affecting all levels of the national educational system. Brazil has faced budgetary contingencies in previous governments, but never as part of an open strategy against the credibility of scientists and their institutions.

In 2019 we also learned that Science entered the long list of endangered species worldwide. It is not coincidental that the Amazon burns while Brazilian scientists get fired and scientific funding gets cut.

The recent case of the dismissal of Ricardo Galvão, an internationally awarded researcher, as the direction of the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), is another example of the dark days Brazilian scientists are facing. Galvão was fired after INPE published a report on the alarming increase in the deforestation of the Amazon.

Preventing scientists from graduating, and silencing those who are doing their jobs, is a threat to decades of dedicated knowledge gathered by national institutions, resulting in devastating global consequences.

The protection of the Amazon is about our very existence on this planet. Yet, much of the responsibility for protecting one of Earth’s most valuable natural resources lies on just one country.

The Amazon extends over nine countries in South America, but 60% of it is located inside the Brazilian territory. This is a key reason why every government concerned with the future of their citizens should work closely with the Brazilian authorities. That also means that declarations of international interference in the Brazilian domestic sovereignty might not be the best strategy to save our planet.

If the Amazon is as important to the whole world as the leaders of the G7 have recognized, then politicians and citizens from developed countries should stand against these attacks and support the Brazilian scientific community.

Scientists are more than technicians. And most of them do not know the power they have in their hands, and how science diplomacy can help to shape the world in crucial times like this. Scientists are political agents, who can lead humanity towards peace and development – or to its devastation.

Science diplomacy is possible because scientific communities are bound by the common pursuit of knowledge. Though not immune to human passions, as a whole, scientists are highly educated citizens, trained in foreign languages, used to international travel, politically aware and occupy leading positions in the public and the private sectors. They can mobilize resources and networks across borders, and inform the public debate on urgent matters such as on how to design sustainable landscapes embracing development and ecosystem services.

Moreover, every country shares responsibility in protecting the Amazon, but it must happen under the rules of cooperation and respecting national sovereignties.

There is nothing new about that. International mechanisms for funding scientific research that will lead us towards a better understanding of the Amazon, its resources, conservation and sustainable use are already defined in the Paris Agreement of 2015 within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Nevertheless, Brazilian scientists have been collaborating and leading international efforts to design solutions to mitigate and adapt in the face of local and global changes.

A classic example is the Large-Scale Biosphere-Atmosphere Experiment in Amazonia (LBA) developed in 90`s to describe the role of the Amazon and its deforestation in the global environment. LBA was funded by NASA, the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology, and a smaller part by European countries – it united 280 institutions worldwide promoting knowledge on how the forest works and its effect on global climate.

Another example is the Amazon Fund. A USD 1.3 billion initiative which invests in projects aimed at preventing, monitoring and combating deforestation, and supporting sustainable development in the Amazon. It is a REDD+ mechanism designed by the Brazilian Government in which developed countries fundraise according to achieved results in avoiding deforestation and promoting sustainable development. The fund supported numerous missions to control deforestation and fire, boosted sustainable productive activities for 162,000 people, and improved management of 190 protected areas. It also supported 465 scientific or informative publications produced by 368 researchers and technicians worldwide.

These are some of the numerous examples of how science can, intentionally or not, generate synergies. Local scientists should mobilize their networks to discover opportunities, exchange ideas and invite to the table their local governments and representatives from the private sector.

This movement must be fostered by the active engagement of transnational funding agencies, scientific networks and Research & Development companies interested in supporting national researchers - the gatekeepers of local knowledge that otherwise will be lost.

Putting pressure on our governments, creating research grants, cooperatively funding, or simply inviting local scientists to speak are just some of the steps we could take to promote science diplomacy for the Amazon.

Gustavo Macedo is a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of São Paulo (Brazil), and Visiting Research Scholar at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University in the City of New York. Andrea Garcia is a is a Ph.D. Candidate in Applied Ecology at the University of São Paulo. She is a 2019 UNESCO’s Young Scientists laureate.

This post first appeared on:

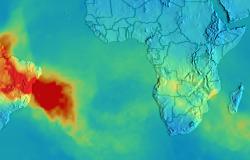

Image credit: AIRS via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)