Beyond the Pledge: Addressing Ambiguities in International Climate Finance Agreements

Ann-Kristin Becker and Ina Sieberichs analyze the outcomes of COP30 regarding climate finance. They argue that without a binding definition of additionality and a rebalancing toward adaptation finance, climate finance risks becoming a double-counting exercise that serves donor interests more than recipient needs.

Climate finance may not have dominated the headlines at the recent COP30 in Belém, but it quietly shaped dynamics in the negotiating rooms. The decision text calls for a tripling of adaptation finance by 2035 relative to 2022 pledges. This adaptation finance is counted toward the “New Collective Quantified Goal” (NCQG) agreed last year at COP29 in Baku. The COP30 call does not mobilize additional funds, remains purely voluntary and non-binding, and in fact weakens the earlier COP29 commitment, which had set the goal of tripling adaptation finance by 2030.

The NCQG, which intends to acknowledge industrialized nations’ historical responsibilities for CO2 emissions, has been widely criticized by vulnerable countries as insufficient. On top of this, we argue that the climate finance agreement leaves two critical points unresolved:

First, it lacks concrete legal definitions, binding accountability measures, and safeguards to ensure that climate finance is genuinely new and additional, rather than redirected from other essential development priorities. At COP30, developed countries even resisted the introduction of indicators to track progress on adaptation finance, further weakening transparency.

Second, the prioritization of mitigation over adaptation skews the allocation of funds toward the interests of donor countries, undermining the needs of countries most vulnerable to climate change. The cautious and fragile decisions taken at COP30 on adaptation finance are far from sufficient to redress this imbalance.

The Problem of "Additionality" in International Climate Finance

Since COP15 in 2009, industrialized countries have committed to mobilizing $100 billion annually for climate finance starting in 2020. According to the NCQG, this amount is to increase (nominally) to $300 billion by 2035. Climate finance includes funds and investments to support climate mitigation efforts, adaptation to the impacts of climate change, and addressing loss and damage from extreme weather events. The COP15 agreement not only set a financial target for international climate finance but also stipulated that climate aid must be "new and additional". This condition was intended to ensure that climate finance does not undermine traditional development goals such as education, healthcare, and poverty alleviation. Nevertheless, a binding regulation defining what constitutes additional climate finance is still lacking, complicating both monitoring and accountability of the financial target.

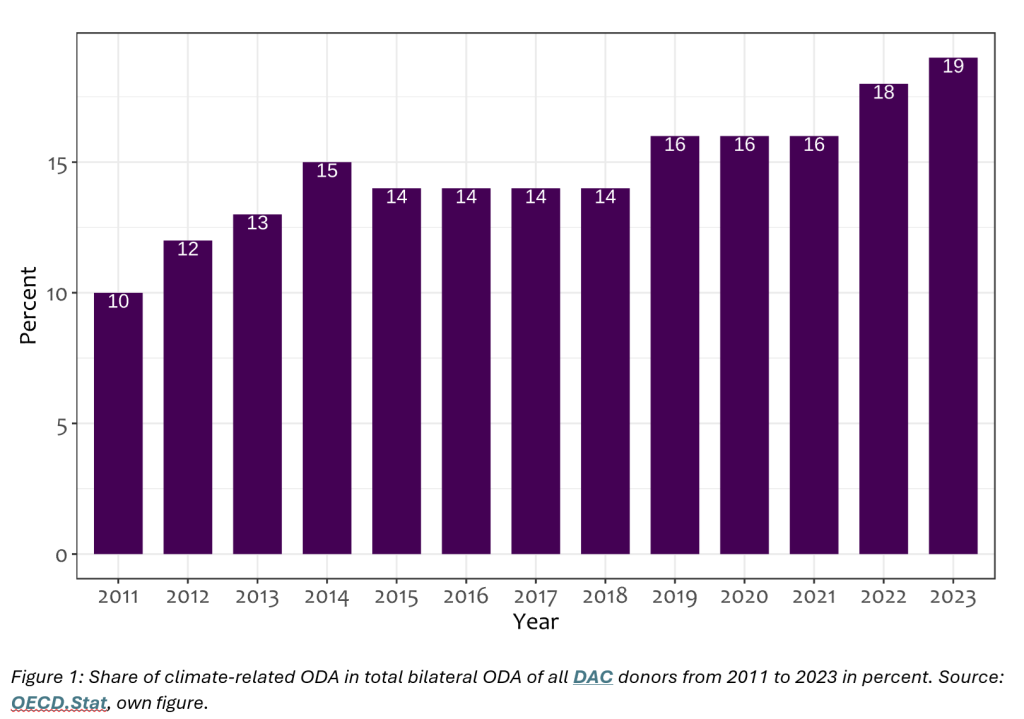

Figure 1: Share of climate-related ODA in total bilateral ODA of all DAC donors from 2011 to 2023 in percent. Source: OECD.Stat, own figure.

In practice, many donor countries fund a significant portion of their climate finance through the budgets of development aid, often without proportionally increasing these budgets. Figure 1 shows the percentage share of climate-related Official Development Assistance (ODA) in total bilateral ODA of all DAC donors from 2011 to 2023.(1) It highlights a consistent upward trend in the share of Climate ODA over the years, rising from 10 percent in 2011 to 19 percent in 2023.(2) This indicates that an increasing portion of overall development aid is being directed toward climate finance.

An analysis conducted by CARE finds similar results. Their study shows that only 7 percent of climate finance from 2011 to 2020 could be considered additional under a strict definition of additionality. This definition counts funds as additional only if they exceed the OECD countries’ ODA target of at least 0.7 percent of GNI. Under a more lenient definition, the level of ODA in 2009 is used as a baseline, with any subsequent increases considered additional. Even then, less than half of the reported climate finance qualifies as additional.

Institutionally, it may be logical to channel climate finance through development ministries, as their existing structures and partnerships can facilitate project implementation. However, without a corresponding increase in the overall budget, this comes at the expense of other critical areas of economic development. It then appears that donors are seeking a double political dividend: by counting the same financial flows twice, they can claim to have met both their climate finance goals and their ODA targets. Moreover, financing climate projects via development budgets could suggest that climate finance is merely altruistic solidarity from industrialized countries to vulnerable countries, rather than an entitlement under the polluter pays principle.

Self-interest in International Climate Finance: Between Climate Mitigation and Adaptation

Beyond fears that climate finance crowds out other priorities, it is also worth examining how funds are prioritized between climate adaptation and mitigation. While climate adaptation measures are largely confined to local populations, climate mitigation, in the sense of reducing global warming, is a global public good. Since every ton of CO2 saved worldwide is equally valuable for climate mitigation, any mitigation measure in a recipient country serves not only the interests of its local population but also those of the donor population.

Under the Kyoto Protocol, it was agreed that it does not matter whether emissions are reduced domestically or abroad. These rules were reaffirmed in the Paris Agreement. From an economic perspective, these crediting rules make perfect sense and make investments in countries in the Global South particularly attractive for reasons of cost efficiency. However, climate mitigation measures in other countries are not solely acts of solidarity for the benefit of those countries. If industrialized countries reduce emissions through development cooperation instead of domestically, they save the financial resources that would have been required to achieve the same reduction within their borders.

Unlike mitigation, adaptation measures mostly have local effects, giving donors little direct interest in funding adaptation in the Global South. Any indirect benefits for them, such as potentially reduced migration, are uncertain and hard to quantify, while recipient countries gain clear, tangible resilience benefits from local adaptation finance.

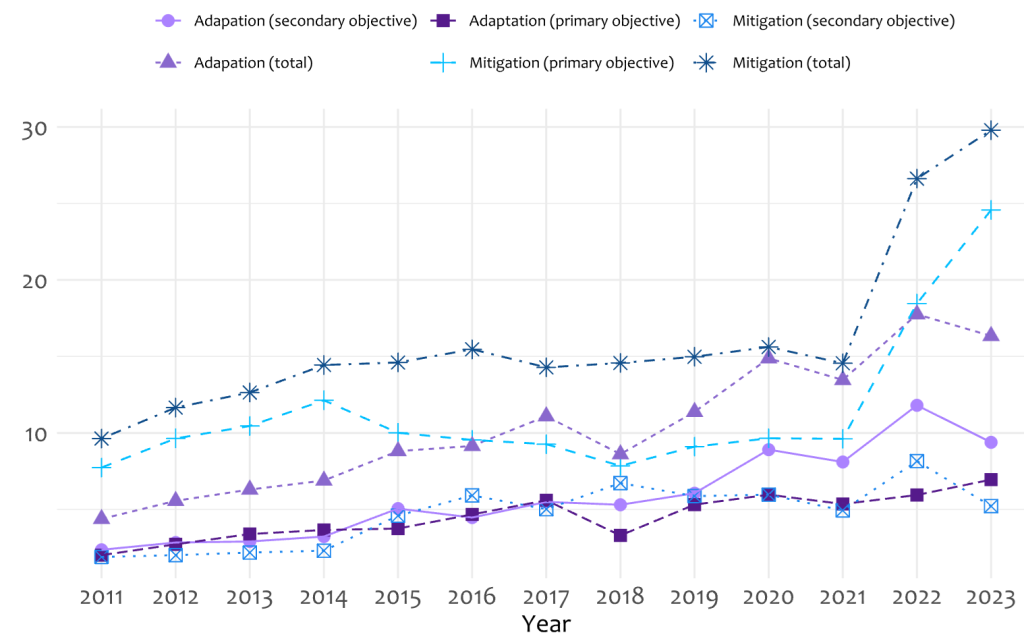

Figure 2: Total commitment in billion USD. Source: OECD.Stat, own figure.

Figure 2 illustrates bilateral ODA commitments for climate mitigation and adaptation projects in absolute terms. The figure shows that funding for climate projects has increased since 2011. It also becomes evident that donor countries have consistently allocated significantly more resources to climate mitigation than to adaptation projects. In 2023, 25 billion USD was spent on projects with the primary goal of climate mitigation, compared to only 7 billion USD for projects primarily focused on adaptation.(3) More than three times the amount of funding has been allocated to climate mitigation compared to adaptation. Donor countries are thus failing to meet their commitment under the Paris Agreement to at least achieve parity in funding for mitigation and adaptation.

Setting the Course for Equitable Climate Finance

Mobilizing climate finance has become increasingly difficult. With public debt mounting and budgets under strain, major donors are reluctant to commit to scaling up their contributions. COP30 achieved an adaptation finance target that counts toward the climate finance target (NCQG) agreed at COP29. However, merely establishing targets for international climate finance is not enough.

To ensure transparency and accountability, a clear international legal definition of additionality is essential. Defining only funds above the 0.7 percent GNI aid target as additional would make climate finance truly “new and additional” rather than displacing development aid, forcing many donors to substantially raise development budgets if most climate finance continues to run through development ministries.

The interests of high-emitting countries should not dominate how funds are split between mitigation and adaptation. In this light, the COP30 call to triple adaptation finance from a very low 2022 baseline is no breakthrough: it weakens earlier commitments and would still leave adaptation below parity. At a minimum, funding parity is needed, as pledged under the Paris Agreement.

Ann-Kristin Becker is a researcher at the Department of Economics at the University of Cologne. More information is available here: Website; LinkedIn.

Ina Sieberichs is a research associate at the Institute for Economic Policy at the University of Cologne. More information is available here: Website; LinkedIn.

Photo by Niklas Jeromin

Footnotes:

- We consider commitments (deflated to 2020 prices), as these reflect donors’ decisions better than actual disbursements. The analysis focuses on bilateral ODA that flows directly from donor to recipient countries.

- To identify the proportion of ODA channeled into climate projects, donors assign so-called RIO markers to each project. The markers indicate whether climate adaptation or mitigation is a primary, secondary, or no objective of the project. Since several secondary objectives can be assigned to a single project and the funding split is unclear, we discount the funds for projects with a secondary objective by 40 percent in accordance with EU guidelines.

- According to the OECD, climate mitigation or adaptation is categorized as the primary objective of a project if this is the fundamental motivation for implementing the project. It is classified as secondary if the project contributes to that objective, but this is not the main reason for implementing it.