The Promotion of the Green Agenda in the Trump Era: Perspectives on Europe’s Role in Agenda Setting with Brazil

Ana Paula Tostes and Yasmin Renne examine the interaction between the EU and Brazil in pursuing environmental goals, and the present geopolitical context, favouring completion of the Mercosur Agreement. This text is part of a forthcoming e-book by the Global Governance Research Group of the UNA Europa network, entitled ‘The European Union in an Illiberal World’.

After World War II, the liberal international order shaped global cooperation and democratic values, with the European Union (EU) serving as both its product and promoter (Featherstone & Radaelli, 2003; Börzel, 2003). Since the end of the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007-2008, however, this order has faced deepening predicaments, including rising populism, weakened democratic norms, and fragmentation within member states.

Applying the concept of “critical junctures” (Pierson, 2000; Collier & Munck, 2024), our analysis identifies three disruptive periods that have affected international cooperation and contributed to the decline of multilateralism. By referencing these sources, we establish a solid theoretical foundation and situate our work within current debates, demonstrating how such disruptions have driven the rise of extreme right ideologies and hindered international governance.

This policy paper then explores the EU and its member states’ evolving climate diplomacy amid global instability, especially during times of low cooperation and efforts to diversify partnerships. Recent events—including the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and leadership shifts like Donald Trump’s return to the U.S. presidency—have strained alliances and underscored the need for adaptable strategies in climate action and economic relations.

Geopolitical and economic disruptions have reshaped the EU’s external climate agenda, particularly in relation to South American nations like Brazil. Heightened competition, protectionism, and realigned alliances have prompted the EU to adjust its foreign policy and seek new avenues to uphold key elements of the liberal order. As supply chains and global power dynamics shift, the EU’s engagement with South America is becoming both strategic and necessary.

To lead in climate diplomacy, the EU is increasingly integrating environmental goals into its trade and development policies, exemplified by sustainability clauses in the EU-Mercosur agreements that link market access to commitments on deforestation and emissions reductions. These measures aim to encourage partner countries to align with international climate standards. Policy developments in Brazil, with its Amazon biome, regional influence, and the policy shift following President Lula da Silva’s re-election in 2022, underscore the importance of this approach. Embedding sustainability requirements advances the EU’s climate objectives and reinforces liberal norms amid uncertainty.

Using a case-based approach, this paper focuses on Brazil and examines two main areas of EU-Brazil relations to evaluate European climate diplomacy's scope and trajectory:

- Values-based strategic cooperation: this refers to the EU's efforts to align its policies and politics with collaborative efforts grounded in shared principles such as democracy, human rights, and environmental protection—exemplified by the EU-Mercosur trade and investment negotiations in South America.[1]

- European green investments: these encompass financial contributions and initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable development and environmental conservation in Brazil, particularly through mechanisms such as the Amazon Fund and related bilateral initiatives.

By analysing these domains of EU-Brazil relations, we aim to clarify how the EU navigates geopolitical fragmentation to sustain its climate commitments and maintain influence in Latin America. In doing so, we also consider the broader implications for the EU’s normative power and the future of multilateral environmental governance. We will continue this step-by-step analytical approach in subsequent sections, by referencing additional specific programs and case studies, such as bilateral funding mechanisms and sustainability clauses in trade deals, in order to assess the EU’s ability to maintain a clear and tangible trajectory as a normative power and support the future of multilateral environmental governance.

Methodological note

We frame our analysis using the concept of critical junctures (Pierson 2000, 2004; Collier & Munck 2024), understood as moments of heightened uncertainty that allow for the strategic reconfiguration of policy and international alignments. We identify three recent junctures: i) the first Trump presidency (2017–2021), ii) the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine (2020–2023), and iii) the second Trump presidency, which began in January 2025. These events have disrupted existing cooperation channels and prompted the recalibration of the EU's climate leadership strategy. More recently, we have also seen a rapprochement of the EU and Latin America, marked by the relaunch of the bi-regional dialogues by the European Union – Latin America and Caribbean (EU-LAC) Foundation, progress on the EU-Mercosur Agreement, and the introduction of a targeted Investment Agenda for LAC under the Global Gateway Strategy (European Commission, 2023).

A qualitative case study approach enables in-depth exploration of complex diplomatic interactions and contextual factors that are not easily captured through quantitative methods, providing nuanced insights into the evolving EU-Brazil relationship. This method is particularly suitable for analysing EU-Brazil green diplomacy because it enables us to closely examine the interplay between political discourse, institutional arrangements, and investment flows, while also addressing challenges such as limited generalizability and potential subjectivity through the triangulation of multiple data sources and perspectives.

The case of EU-Brazil relations was selected based on its strategic significance for EU foreign policy along three dimensions: i) Brazil's leadership within Mercosur and central role in the EU-Mercosur trade agreement; ii) the ecological relevance of the Amazon biome; and iii) the recent political shift toward environmental re-engagement under the new left-wing administration of President Lula. Among Latin American countries, Brazil's unique combinations of influence, environmental assets, and recent political shifts make it an especially revealing context for studying the intersection of climate diplomacy and foreign policy realignment. Brazil thus offers a critical case for observing how the EU operationalises its climate diplomacy in a high-stakes, geopolitically sensitive context.

Our investigation continues to connect the theoretical framework of critical junctures to specific policy developments, providing a coherent analytical structure that links theory to practice. We examine how the EU, leading member states (including Germany and France), as well as Norway (not an EU member), have interacted with Brazil through values-based trade diplomacy and environmental funding, such as the Amazon Fund. Particular attention is given to shifts in political discourse, institutional arrangements, and investment flows that reflect the evolving alignment of climate goals and foreign policy interests.

The EU climate diplomacy under strain

The EU positions itself as a normative power and a global leader in environmental governance, with sustainability at the core of its policies. The European Green Deal (2019) sets a target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, thereby strengthening the EU’s international role through cooperation and binding commitments. Subsequently, the Global Gateway (GG) strategy, launched in July 2021, aims to invest over €300 billion in sustainable infrastructure and climate adaptation in developing countries, offering an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (European Commission, 2021). Simultaneously, the EU has emphasised its commitment to aligning trade and development policies with environmental goals, reinforcing a values-based approach that distinguishes it from its geopolitical competitors.

The war in Ukraine has accelerated the EU’s energy security concerns and expanded the GG’s focus on Latin America, with a particular emphasis on Brazil, due to its economic strength and significance for climate efforts. These changes reflect the EU’s shift from general development finance to targeted regional partnerships, using the GG Investment Agenda (GGIA) to promote renewable energy and resilience. For the EU, this means diversifying energy and supply chains, while partner countries, such as Brazil, benefit from financing and “climate collaboration”, when we consider the Amazon Fund for example.

More recently, the EU has designated a donation of €20 million to the Amazon Fund – a mechanism created to raise donations for non-reimbursable investments in efforts to prevent, monitor and combat deforestation, as well as to promote the preservation and sustainable land-use in the Amazon. The agreement, formalized in November 2025 during the COP30, is a cooperative effort to fight deforestation and protect the region's biodiversity, and it is part of a broader partnership that also includes other energy transition and digital economy projects in Brazil (COP30, 2025).

Overall, the EU’s climate diplomacy leverages strategic initiatives and regional adaptations to maintain climate commitments and influence global standards amid intensifying competition and geopolitical disruption. The European Commission's REPowerEU plan is one example (European Commission, 2025). Launched in 2022, it aims to increase renewable energy production in Europe. This pursuit of increased renewable energy production in Europe has led to a search for diversified partnerships and investments in developing countries, with Brazil as a key one.

Brazil as a strategic partner in EU green diplomacy

Brazil is vital to the EU’s climate strategy, being South America’s largest economy and home to most of the Amazon rainforest. The EU-Mercosur agreement, delayed due to concerns over Brazil's environmental policies under President Jair Bolsonaro’s government, gained new momentum after Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s election and renewed climate commitments. Improved governance and reduced deforestation reopened talks, while shifting global politics have made closer EU-Mercosur ties more attractive. This section explores how EU-Brazil relations have evolved in two critical domains: 1) values-based trade cooperation through the EU-Mercosur agreement, and 2) environmental investment via initiatives such as the Amazon Fund. These cases illustrate how the EU adapts its green diplomacy in response to shifting domestic and international contexts.

1. The EU-Mercosur Agreement and norm-based trade diplomacy

The EU-Mercosur agreement, first proposed in the 1990s, reached a breakthrough in 2019 amid growing tensions in global trade and the weakening of multilateral institutions. However, the agreement's ratification stalled shortly thereafter, primarily due to concerns about environmental governance in Brazil under President Jair Bolsonaro. Widespread deforestation in the Amazon, coupled with Bolsonaro’s dismantling of key climate institutions, led countries like France to oppose the deal, citing violations of environmental and human rights standards. The opposition to the ratification of the EU-Mercosur Agreement was manifested by President Emmanuel Macron and the declaration of the Presidency was approved by France’s National Assembly in November 2024 by a large majority (Le Monde, 2024).

The political landscape shifted dramatically with the re-election of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2022. Lula’s administration, in contrast to his predecessor, has signalled a renewed commitment to climate protection, institutional rebuilding, and the reactivation of Brazil’s international environmental diplomacy. The appointment of Marina Silva — a globally respected environmentalist— as Minister for the Environment further reinforced these commitments. Under Lula's administration, deforestation dropped by over 30% in the Amazon biome and by approximately 26% in the Cerrado biome in the first months of his administration, according to data from PRODES – the system that integrates the Brazilian Biomes Monitoring Program (BiomasBR) of the National Institute for Space Research (INPE). This marked an clear reversal of Bolsonaro-era policies (Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima, 2024).

These developments reopened space for EU-Mercosur negotiations. While European concerns about agriculture and trade protections persist—particularly in France, where, for instance, French farmers have expressed worries about increased competition from Mercosur countries, fearing it could undermine local agricultural standards and livelihoods—growing geopolitical uncertainty following the election of Donald Trump to a second term has softened resistance. The renewed US administration’s approach to international trade and climate policy has prompted the EU to reconsider its strategic alliances, making closer ties with Mercosur increasingly attractive in the current global context (Malmström, 2025; Nolte & Tostes, 2025).

Recent statements by French parliamentarians (Corlin, 2025) suggest a more pragmatic stance, driven by the need to diversify economic partnerships and counterbalance US unilateralism. Brazil’s environmental turnaround has helped remove one of the significant obstacles to ratification, positioning the agreement as a key opportunity for green-oriented trade diplomacy.

2. The Amazon Fund and European environmental investment

Created in 2008 under Lula’s first administration, the Amazon Fund finances efforts to prevent deforestation and promote sustainable development in the biome. Supported by international donors, primarily Norway and Germany, the Fund became a flagship mechanism for climate cooperation and biodiversity protection. However, during the Bolsonaro Presidency, the Fund was effectively suspended: environmental oversight bodies were dismantled, and accusations of mismanagement were used to block new contributions, severely undermining Brazil’s forest governance.

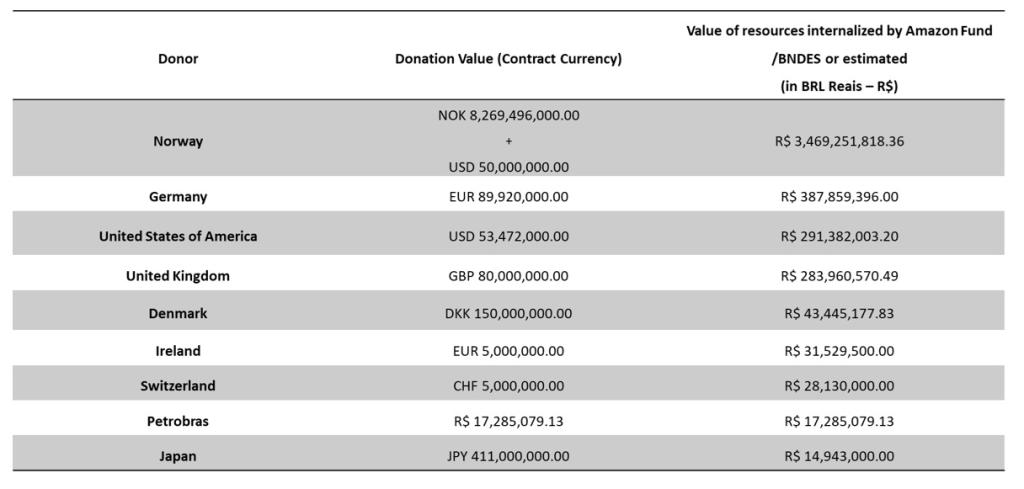

Table 1. Donations by country and internalised values

Source: Fundo Amazônia 2025

The reactivation of the Fund under Lula’s third administration was a result of the relaunch of mechanisms to control deforestation and financial oversight through the Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES), enabling the Fund’s governance to meet international transparency standards.

New multilateral initiatives have also emerged. The Green Coalition, comprising the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), BNDES, and Brazil’s Ministry of Planning, aims to mobilise between $10 billion and $ 20 billion in sustainable investment across the Amazon region between 2024 and 2030 (Inter-American Development Bank, 2023). This cooperation reflects a growing recognition of the Amazon as a global public good and Brazil as a crucial partner in achieving climate goals, as approximately 60% of Brazilian territory is covered by the Amazon biome (see Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima, 2021).

The EU's consistency in pursuing policies in these two domains—trade and environmental diplomacy—illustrates the adaptive nature of the EU’s engagement in international cooperation and search for influence in a fragmented world order. Brazil’s domestic political changes have created a window of opportunity for renewed cooperation, while the international multilateral order is at risk. For the EU, deepening engagement with Brazil reinforces both strategic interests (such as access to the regional market and access to critical raw materials, to reduce energy dependencies on Russia, while supporting the energy transition in the region) and normative goals (such as deforestation reduction and biodiversity preservation).

As geopolitical volatility has increased with the Trump administration announcing a nationalist policy of increasing import tariffs in April 2025, Brazil is likely to remain a cornerstone of Europe’s climate diplomacy. The EU-Mercosur Agreement thus becomes an even more viable option, as it guarantees a reduction of around 91% in tariffs on EU exports to Mercosur over 15 years, including for automobiles; and the elimination of approximately 92% of tariffs on Mercosur exports to the EU within a period of up to 10 years. Depending on goods categories, these reductions could reach 100% (see Siscomex, 2021; Reuters, 2024).

Preliminary considerations on strategic priorities for EU-Brazil Green Diplomacy

Brazil has returned to the centre stage of international climate governance, via the reactivation of the Amazon Fund, deforestation reductions, and the climate leadership sought by the country by hosting the COP30 in Belém (in the middle of the Amazon), in November 2025. These shifts have created a renewed window for meaningful EU-Brazil cooperation. In parallel, the EU has responded to global turbulence by reaffirming its climate leadership through initiatives such as the European Green Deal, the Global Gateway, and the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR 2023/1115), which will come fully into force on January 1, 2027, requiring companies (European and foreign companies that export to the EU) to prove that their products do not cause deforestation.

However, the political window may be short-lived. Brazil faces presidential elections in 2026, and Lula’s approval ratings have been weakened by domestic economic constraints. The uncertainty surrounding a potential far-right resurgence—akin to Bolsonaro’s climate obstructionism—could once again undermine environmental cooperation and disrupt the momentum for finalising the Agreement between the two blocs. For the EU, finalising the agreement and deepening climate partnerships before Brazil’s next elections is not only strategically important but urgent. For Brazil, the agreement could serve as a protective measure against Donald Trump's attempts to use import tariffs as a political threat and a tool of influence warfare.

To safeguard and advance EU-Brazil climate cooperation, three priorities demand immediate attention: 1) finalising trade and climate agreements while political conditions remain favourable; 2) institutionalising green cooperation to withstand electoral cycles; and 3) deepening EU member state engagement with concrete, well-funded action. These steps are urgent given Brazil’s 2026 presidential election, the risk of political reversal, and intensifying global competition for climate leadership.

Recommendation 1: finalise agreements while political conditions are favourable

Accelerating negotiations on trade and climate frameworks with Brazil before the 2026 elections is critical. Political shifts have previously undermined environmental agreements, as seen when the EU–Mercosur pact stalled under President Bolsonaro due to weakened climate commitments and a surge in deforestation. A similar reversal remains possible if political winds change. This entails prioritising the conclusion of the EU-Mercosur and climate partnership agreements by mid-2026, and mobilising high-level EU diplomatic missions to maintain momentum and resolve outstanding disagreements, especially regarding deforestation-linked imports.

Recommendation 2: institutionalize green cooperation beyond political cycles

Embedding climate collaboration in legally binding, transparent frameworks ensures continuity regardless of electoral outcomes. The Amazon Fund’s recent success—deforestation in Brazil dropped by 32.4% in 2024 following its reactivation under President Lula—demonstrates the impact of sustained, multi-donor support. To this end, long-term funding mechanisms through the Amazon Fund, BNDES, and the Green Coalition, needs to be expanded, to help ensure all agreements include legal safeguards and independent oversight. Moreover, joint monitoring systems for deforestation and emissions need to be institutionalised, making data publicly available to reinforce accountability. Finally, the IDB’s 2024-2027 strategic partnership with Brazil should be highlighted as a model for resilient cooperation, given its funding of large-scale renewable energy projects in the Amazon.

Recommendation 3: enhance EU Member State engagement and coherence

For the EU’s climate diplomacy to succeed, Member States must move beyond rhetoric and align trade, climate, and geopolitical interests. France’s recent softening of its opposition to the Mercosur deal—prompted by concerns over U.S. protectionism—signals a window of opportunity for unified engagement. Concerning Brazil, this entails adopting a proactive, well-funded strategy supporting Brazil’s institutional capacity and respecting its development priorities. Coherence across EU policies, preventing contradictions between trade, climate, and foreign policy objectives, is also important. Finally, there is scope to provide technical assistance to Brazil’s legislative and enforcement bodies to sustain deforestation controls, especially as domestic opposition challenges environmental regulation.

Recommendation 4: strengthening the role of development banks

Development banks like BNDES and the IDB are essential for channelling climate investments, coordinating governance, and supporting local priorities. Their effectiveness is illustrated by BNDES’s co-financing of the “Amazon Sustainable Landscapes” project, which has restored over 1.5 million hectares of degraded land since 2019. Such success calls for: i) more joint EU–Brazil development bank initiatives focused on renewable energy, forest conservation, and sustainable agriculture; ii) enhanced governance standards and transparency in project selection and implementation; iii) supporting the exchange of knowledge between EU and Brazilian banks to accelerate green finance innovation.

Overall, there is a time-sensitive opportunity in place. The EU and Brazil have a narrow window to solidify their climate partnership and set new global standards. Decisive, coordinated action is essential to pre-empt political reversals and maximise the impact of recent environmental gains. This urgency should be consistently emphasised in future policy briefs, executive summaries, or research to guide high-level decision-making.

Ana Paula Tostes is a full Professor at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) and Jean Monnet Chair of the European Union (JMC-UERJ). She is a Senior Fellow at the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI), and a Senior researcher at FAPERJ and CNPq, member of the strategic core of the Interdisciplinary Observatory of Climate Change (OIMC). She was a visiting professor at the Center for European Studies at the Free University of Berlin (ULB, Germany), a postdoctoral fellow and visiting professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of São Paulo (USP), and a visiting and associate professor at the Department of Political Science and at James Madison College (JMC), Michigan State University (MSU, USA). Her research and teaching work focus mainly on European studies, the European Union, international institutions, regional integration, and climate diplomacy.

Yasmin Renne is a PhD student in International Relations at the EU at NOVA University in Lisbon and a project team member as a Jean Monnet Chair (JMC-UERJ). She holds a master's degree in International Relations from the Graduate Program in International Relations at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (PPGRI-UERJ) (2018) and graduated in Economic Sciences from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (2014), with an academic exchange at Università di Bologna (2012) and specialisation in International Business Management by IBMEC-RJ (2015). She is currently working in the private sector in Spain and Portugal. Her main areas of interest in teaching and research include the European Union, Europeanization, International Political Economy, the GDPR, and the EU Digital Agenda in the context of the green transition.

Photo by Diego Rezende

Endnotes

[1] Although EU institutions claim a long tradition of value promotion, the concept was more explicitly incorporated with the Treaty of Lisbon (Article 2). It established the rights to human dignity, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights as core values of the Union, both within it and in its external relations. Furthermore, the Charter of Fundamental Rights reiterated this general framework for values and principles of the EU, which is mirrored in different policy areas, including the Common Commercial Policy and values-based clauses on EU trade agreements. (European Union, n.d.; European Council, n.d.)

References

Börzel, T.A. (2003). Shaping and Taking EU Policies: Member States Responses to Europeanisation. Queen’s Papers on Europeanisation. n.2

Collier, David; Munk, Gerardo L. (2024). Critical Junctures and Historical Legacies: Insights and Methods for Comparative Social Science. Rowman & Littlefield Publisher.

COP30. (2025) Amazon Fund Quadruples Approvals and Expands Reach in Climate Finance Push. 19/11/2025. Available at: https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/amazon-fund-quadruples-approvals-and-expands-reach-in-climate-finance-push

Corlin, Peggy. (2025). France’s united front against Mercosur deal starts to show cracks. EuroNews. 15/-4/2025. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/04/15/frances-united-front-against-mercosur-deal-starts-to-show-cracks

European Commission (2021). Global Gateway: up to €300 billion for the European Union's strategy to boost sustainable links around the world. Brussels, 01/12/2021. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6433

European Commission (2023). JOINT COMMUNICATION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL: A New Agenda for Relations between the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean. JOIN(2023) 17 final. Brussels, 07/06/2023. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52023JC0017

European Commission (2025). REPowerEU. Affordable, secure and sustainable energy for Europe. (website) Last Updated 17/06/2025. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/topics/energy/repowereu_en

European Council. (n.d.) Promoting EU values through trade. (website) https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/trade-policy/promoting-eu-values/

European Union. (n.d.) Aims and Values (website). https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/principles-and-values/aims-and-values_en

Featherstone, Keith & Radaelli, Claudio (eds.) (2003). The Politics of Europeanization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

France 24. (2023). Germany's Scholz heads next to Chile, Brazil on Latin America tour. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230128-germany-s-scholz-to-meet-brazil-s-lula-on-l-american-tour

Fundo Amazonia.(website) https://www.fundoamazonia.gov.br/pt/home/

Gov.br. Desmatamento no Brasil caiu 32, 4% em 2024. Meio Ambiente. 15/05/2025. https://www.gov.br/secom/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2025/05/desmatamento-no-brasil-caiu-32-4-em-2024

Inter-American Development Bank. (2023).The Green Coalition of Public Development Banks Aspires to Mobilize as Much as $20 Billion for Amazon’s Sustainable Development. 01/12/2023. Available at: https://www.iadb.org/en/news/green-coalition-public-development-banks-aspires-mobilize-much-20-billion-amazons-sustainable

Inter-American Development Bank. (2024). Brazil and IDB Group Strategic Agreement Country Strategy. 2024-2027. November. Available at: https://idbinvest.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/Country%20Strategy%20with%20Brazil%202024-2027-Final%20version.pdf

Le Monde (2024). EU-Mercosur trade deal: French lawmakers overwhelmingly reject treaty in non-binding vote. 27/11/2024. Available at: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2024/11/27/eu-mercosur-trade-deal-french-lawmakers-overwhelmingly-reject-treaty-in-non-binding-vote_6734278_5.html

Malmström, Cecilia. (2025). The European Union is forging a new strategic alliance with Latin America. Peterson Institute for Economics. Available at: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/european-union-forging-new-strategic-alliance-latin-america

Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima. (2021). Amazônia. 28/12/2021. Available at: https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br/assuntos/biodiversidade-e-biomas/biomas-e-ecossistemas/biomas/amazonia

Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima. (2024). Prodes. Desmatamento cai 30,6% na Amazônia e 25,7% no Cerrado em 2024. Available at: https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/taxa-de-desmatamento-na-amazonia-cai-30-6-e-25-7-no-cerrado

Nolte, Detlef; Tostes, Ana Paula (2025). União Europeia. A contracorrente: o acordo UE-Mercosul e a política comercial de Trump. 06/02/2025. Available at: https://latinoamerica21.com/en/against-the-tide-the-eu-mercosur-agreement-and-trumps-trade-olicy/

Pierson, Paul. (2000). “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics”. The American Political Science Review, 94 (2), pp. 251–267.

Pierson, Paul. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Reuters. (2024). What's in the newly finalised EU-Mercosur trade accord? 06/12/2024. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/whats-newly-finalised-eu-mercosur-trade-accord-2024-12-06/

Siscomex. (2021) 2a: Anexo Sobre Cronogramas de Desgravação Tarifária. Available at: https://www.gov.br/siscomex/pt-br/arquivos-e-imagens/2021/07/2a-anexo-sobre-cronogramas-de-desgravacao-tarifaria-pdf.pdf