Sports and the Making of the Modern World

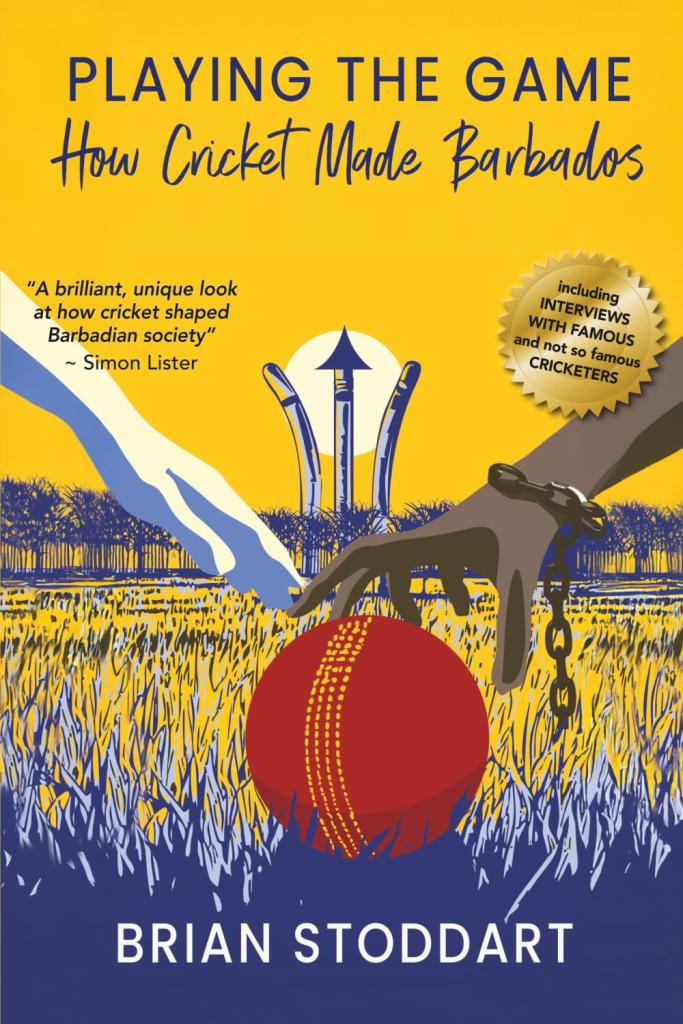

Brian Stoddart asks how tiny Barbados, with a population rarely exceeding 250,000 and a history devilled by slavery and its aftermath, for so long produced so many of the world’s best players in that most English of games, cricket?

In my new book, I suggest it was because the game became central to the social reordering of Barbadian society following the abolition of slavery. By 1914 the main teams were organised along tightly delineated class, caste and colour divisions: white elite, white middle class, respectable brown and respectable black. Teams from the schools followed the same lines, while plantocracy-based teams reinforced the pattern. That was all further reinforced in the interwar period when an entirely separate competition was created for the black masses.

CLR James outlined this Caribbean condition in his magisterial Beyond a Boundary and the importance of cricket in the regional colonial/postcolonial story has been generalised rather than detailed by other scholars and commentators, with the wonderful exception of Clem Seecharan in his recent work on Guyana.

For Barbados, though, the archival trawl in both cricket and social history waters has been enriched by two further sources: interviews with unknown as well as known past players; and my experiences as a player (the only white at the time) in a period when West Indies and Barbados were unchallenged champions and the old social patterns were being disrupted, slowly.

As I note in the book, the club for which I played had a home ground carved out of a plantation where historians believe up to 30,000 slaves lived and died. For close to one hundred and fifty years now, then, cricket in Barbados has been the touchstone for social layering and the ensuing struggle between tradition and change. Players like Sir Everton Weekes had to fight to get out of that separate black competition and into the one from where he might be selected for Barbados then West Indies. Earlier, Fitz Hinds could not play for Barbados because he was a “professional” player (a groundsman and net bowler for a white club) – but was good enough to be selected for a 1900 Caribbean team that toured England.

As I note in the book, the club for which I played had a home ground carved out of a plantation where historians believe up to 30,000 slaves lived and died. For close to one hundred and fifty years now, then, cricket in Barbados has been the touchstone for social layering and the ensuing struggle between tradition and change. Players like Sir Everton Weekes had to fight to get out of that separate black competition and into the one from where he might be selected for Barbados then West Indies. Earlier, Fitz Hinds could not play for Barbados because he was a “professional” player (a groundsman and net bowler for a white club) – but was good enough to be selected for a 1900 Caribbean team that toured England.

But we must not imagine this remarkable Barbados story was unique or exceptional, because I would argue that the whole of modern sports demonstrate the same patterns; being established to serve a specific social purpose, then later coming under pressure to change in the face of broader social upheaval.

Just a few weeks ago I spent a marvellous day at the Ryogoku Kokugikan in Tokyo during the May Grand Sumo tournament. Here is one of the oldest professional sports in the world, and during this two week schedule the central focus was on whether or not the new phenomenon Onosato could win and be elevated to the elite Yokozuna rank. He could, and did, to huge popular acclaim. And that was because he was the first Japanese in almost a decade to reach that peak which since the 1980s has been dominated by foreigners, Hawaiians and Samoans to begin with but Mongolians since. For a cultural practice soaked in the Shinto tradition and Japanese social mores, this has been a struggle of faith.

At the other end of the Pacific in my home nation of New Zealand, rugby union has for a century or more been the yardstick for the progress of the nation, first as a settler state then more latterly as a multicultural one. It, too, has seen the cycle of tradition being challenged. As Maori became prominent in the game, joined later by players of Pacific Islands origin, relations with that other rugby-dominated culture in South Africa became complicated by differing race relations policies. One yardstick of this social progression may be seen in the haka. Its earlier puny manifestations in the hands of largely white players have given way to the full throated spectacles displayed by a newer cultural generation determined to honour Maori traditions. But, it is important to note, little or none of that goes unchallenged either domestically or internationally with critics questioning the role of the haka.

Rugby union also demonstrates another massive social shift occurring in global sport. In New Zealand now, the women’s national team gets as much notice and often more than the men’s, and that pattern is now well established across the globe as, again, broader social change more than a century in the making begins to triumph.

Then, in recent years we have seen the Gulf States, particularly, begin to use sport as an international diplomatic and promotional vehicle, and that has given rise to the idea of “sportswashing” becoming part of a broader “greenwashing” process. LIV Golf is the most spectacular of these ventures, perhaps, but the massive funding of soccer/football leagues in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere is noticeable, and the practice has extended even to sports like snooker. All of this has a social purpose that has changed significantly from that which applied at the time of those sports’ formal organisation.

And, full circle back to cricket, what was a Barbadian and West Indian supremacy is now replaced by old powers England and Australia but more notably a new one, India. Not only has that country become competitive on the field, it now dominates the game’s commercial and governance spheres with massive repercussions structurally. And cricket is at the forefront for much of India’s ascending international outreach.

The Barbados story, then, is a spectacular one, but it is also instructive not only for what it represents and captures nationally, including its present social and financial pressures, but also because of what it displays about sport’s much deeper than imagined social impact.

Brian Stoddart is a writer of fiction and non-fiction who is now based in Melbourne, Australia. Born and educated a Kiwi he has worked around the world as an academic, university executive, aid and development consultant, broadcaster, commentator and blogger. He has written extensively on sports history, politics and culture as well as on India and south Asia in which field he completed his PhD. Stoddart also works as an international higher education consultant on programs in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Syria and Jordan as well as in the UK and USA. This work follows a successful career as university researcher, teacher and senior executive which culminated in a term as Vice-Chancellor and President of La Trobe University in Australia where he is now an Emeritus Professor. That academic career took him all over the world including long periods in India, Malaysia, Canada, the Caribbean, China and Southeast Asia.