Trustbreakers: How Political Discrimination Shapes Trust in Public Institutions in the European Union

Ana María Montoya and colleagues at the World Justice Project examine the way the feeling of political discrimination erodes trust in democratic institutions supposed to be neutral. The chapter is part of a forthcoming e-book by the Global Governance Research Group of the UNA Europa network, “The European Union in an Illiberal World.”

Across European democracies, the last decade has been marked by intensifying political polarization, the rise of populist movements, and growing disillusionment with traditional political institutions (Nord et al, 2024). This environment has brought renewed attention to a troubling yet underexplored phenomenon: political discrimination. Citizens throughout the European Union (EU) increasingly report feeling excluded, stigmatized, or even harassed because of their political views. Whether stemming from mainstream party opponents, media narratives, or institutional biases, political discrimination appears to be shaping both how citizens relate to public institutions and how they choose to engage in political life.

While a robust body of research has examined the role of discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, or gender in shaping political behavior, less is known about how discrimination grounded in political opinion affects institutional trust. The dominant narrative around civic engagement tends to overlook the experience of political exclusion, treating partisan identity as a driver of opinion rather than a source of discrimination. This omission is particularly significant in the European context, where multiparty systems, coalition politics, and diverse political cleavages complicate the binary logic of partisan divides seen in other contexts, such as in the United States.

This chapter addresses this gap by asking: How does political discrimination influence trust in political institutions? We examine the direct effect of political discrimination on institutional trust and the complex relationship between political exclusion. Drawing on original data from the World Justice Project’s EUROVOICES initiative – a cross-national survey spanning 27 EU Member States and 110 subnational regions – we identify systematic patterns that link experiences of political discrimination to weakened trust. By focusing on both individual-level experiences and subnational variations across NUTS regions, the EUROVOICES dataset provides an invaluable foundation to analyze the societal impacts of perceived political discrimination. The inclusion of this specific dimension enables a rigorous empirical examination of how political exclusion shapes democratic attitudes and behaviors across Europe.

Europe offers a particularly fertile context for examining political discrimination, affective polarization, and their impact on institutional trust. Unlike the United States, where partisanship is often treated as a stable identity, European party affiliations are shaped by enduring socioeconomic, religious, and cultural cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan 1967; Richardson 1991), now layered with newer divides such as globalization, immigration, and European integration. These overlapping fault lines intensify the potential for perceived political exclusion. Moreover, the EU’s institutional diversity – from proportional to majoritarian systems, and from centralized to decentralized governance – provides a valuable comparative framework for analyzing how political arrangements either mitigate or exacerbate polarization (Drutman 2019; Lelkes and Westwood 2017). While coalition politics can sometimes temper binary partisan hostility, they may also contribute to fragmented publics and complex exclusion dynamics. By analyzing how citizens experience political discrimination across these varied contexts, this study sheds light on the broader relationship between polarization, political exclusion, and trust in democratic institutions. Our findings indicate that political discrimination significantly erodes institutional trust.

This chapter has important implications for EU policy. From a policy perspective, the findings suggest a few avenues. Strengthening anti-discrimination norms to include political opinion could help (for instance, discouraging employers, universities, or social platforms from penalizing individuals for lawful political expression). Promoting cross-partisan dialogue and bridging social capital can reduce mutual misperceptions and de-escalate the sense of being under threat that drives affective polarization. Moreover, bolstering the impartiality and fairness of institutions – for example, through independent judiciaries and media pluralism – can reassure citizens that no matter who they are or what they believe, they will be treated equally, thus shoring up trust.

Finally, it is worth noting that while political discrimination in Europe has not been studied as extensively as ethnic or religious discrimination, it is increasingly salient in an era of polarization. Democratic institutions depend on a baseline level of mutual tolerance among political rivals and a belief that one’s rights will be protected even if one’s side is in the minority. When that breaks down, we see the symptoms documented in this review: plummeting trust, voter apathy for some and radicalization for others, street politics supplanting parliamentary politics, and a breeding ground for authoritarian populism.

Literature review and theoretical framework

While the study of political participation and institutional trust has long emphasized the role of social and economic cleavages, less attention has been paid to how individuals’ political identities themselves become targets of exclusion and marginalization. Political discrimination – defined as unfair treatment or stigmatization on the basis of political beliefs or affiliations – has become an increasingly relevant form of grievance in contemporary democracies. In the EU context, this phenomenon is heightened by the diversity of political systems and the rising salience of ideological polarization.

Early studies on political behavior often assumed that democratic systems protect pluralism and tolerate dissenting views. However, recent research has challenged this notion by showing that political exclusion can be institutionalized through biased policymaking, media representation, or social norms (Mudde, 2007; Norris & Inglehart, 2019). The literature on "democratic backsliding" has identified political discrimination as a key tactic used by illiberal governments to delegitimize opposition groups, often by portraying them as disloyal, dangerous, or unworthy of equal participation (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018).

Recent scholarship by Oskooii (2016; 2020) has advanced our understanding of discrimination’s political consequences by distinguishing between societal discrimination (i.e., exclusion by peers or communities) and political discrimination (i.e., biased treatment by political authorities or institutions). Oskooii finds that the perception of political discrimination tends to motivate civic and political action, whereas social or interpersonal discrimination often correlates with withdrawal or alienation.

The literature on political trust highlights how perceived fairness, inclusion, and responsiveness underpin citizens’ willingness to support democratic institutions (Levi & Stoker, 2000; Citrin & Stoker, 2018). When citizens believe that institutions are biased or unresponsive to their concerns – especially if they experience discrimination – they are less likely to view those institutions as legitimate. As Wilkes and Wu (2018) demonstrate, even in democratic contexts, minority groups often experience persistent structural exclusion, which translates into lower levels of institutional trust. These effects are magnified when discrimination is not just intergroup but institutionalized – when the courts, police, or administrative systems are seen as favoring dominant identities. This dynamic is evident in comparative studies showing that perceived partisan bias in institutions reduces trust among opposition voters (Anderson & Tverdova, 2003; Armingeon & Guthmann, 2014). In such environments, trust is no longer grounded in performance but becomes contingent on group belonging, with deep implications for civic cohesion and democratic legitimacy (Keefer & Scartascini, 2022; Glaeser et al., 2000). Therefore, political discrimination is not just an interpersonal experience but a systemic concern.

This breakdown of trust is further intensified in polarized societies where identity-based cleavages, often rooted in experiences of discrimination, become the main lens through which institutions are interpreted. Affective polarization amplifies this process by transforming political opponents into moral enemies (Iyengar et al., 2019). Under such conditions, public institutions are no longer seen as neutral arbiters but as partisan instruments serving the interests of the dominant coalition (Lelkes & Westwood, 2017).

The experience of political discrimination operates within this dynamic, both reflecting and reinforcing the loss of shared moral ground. When individuals believe they are treated unfairly due to their political beliefs, they interpret this exclusion as part of a broader system that no longer protects their rights or values. This perception, in turn, weakens their attachment to democratic institutions and fosters disengagement or radicalization. Moreover, discrimination fractures horizontal trust among citizens, deepening divisions and eroding the civic norms that underpin democratic cooperation (OECD, 2024; Keefer & Scartascini, 2022). In this way, political discrimination not only reduces institutional trust directly, but also indirectly – by disrupting the social fabric through which collective democratic commitments are sustained.

In short, political discrimination emerges in the literature as both a driver and a consequence of affective polarization and declining trust. The net outcome depends on individual, group, and systemic factors – a complexity that this paper seeks to unpack through empirical analysis of the EUROVOICES dataset. We thus hypothesize the following:

H1: Political discrimination is negatively associated with trust in political institutions.

H1b: The negative relationship between political discrimination and institutional trust is stronger among individuals with high levels of affective polarization.

Data and methods

To test these hypotheses, we use household data from the EUROVOICES project, developed by the World Justice Project with support from the European Commission. The dataset comprises responses from 64,089 individuals across 110 subnational regions in the 27 EU Member States. It offers unique and up-to-date information on how people in the EU perceive and experience democratic governance, discrimination, trust in political institutions, and patterns of political engagement in their daily lives. The survey features a detailed module that captures 11 distinct types of discrimination, including sex, age, disability, ethnicity, migration background, socioeconomic status, religion, and political opinion. Respondents are asked whether they have experienced discrimination or harassment in the past 12 months due to these characteristics, with standardized response options that facilitate cross-national comparisons.

Crucially, the survey includes a direct question on political discrimination, asking respondents whether they felt discriminated against or harassed because they expressed political opinions, defended the rights of others, or were affiliated with a political group. This provides a rare opportunity to explore how perceived political discrimination – as distinct from other forms of marginalization – relates to broader questions of institutional trust and democratic participation.

Furthermore, the questionnaire collects data on perceptions of trust in various public institutions, including local and national governments, the police, and judges and magistrates. For this analysis, responses are recoded such that “A lot” and “Some trust” are assigned a value of 1, while “A little” and “No trust” are assigned a value of 0. To better capture an individual's overall trust in political institutions, we developed a Trust in Political Institutions Index. This index was estimated using a Logistic Principal Component Analysis reduction (Landgraf & Lee, 2020) of the individual’s answers to their levels of trust in local authorities, national authorities, police, prosecutors, public defense attorneys, judges, magistrates, political parties, and members of Parliament. Finally, we employ logistic and linear regression models to estimate the effects of political discrimination on institutional trust. All models include country fixed effects and control for age, gender, education, employment, income, minority status, political ideology, and urban/rural residence. Interaction terms are used to test the moderating effect of partisan alignment and affective polarization.

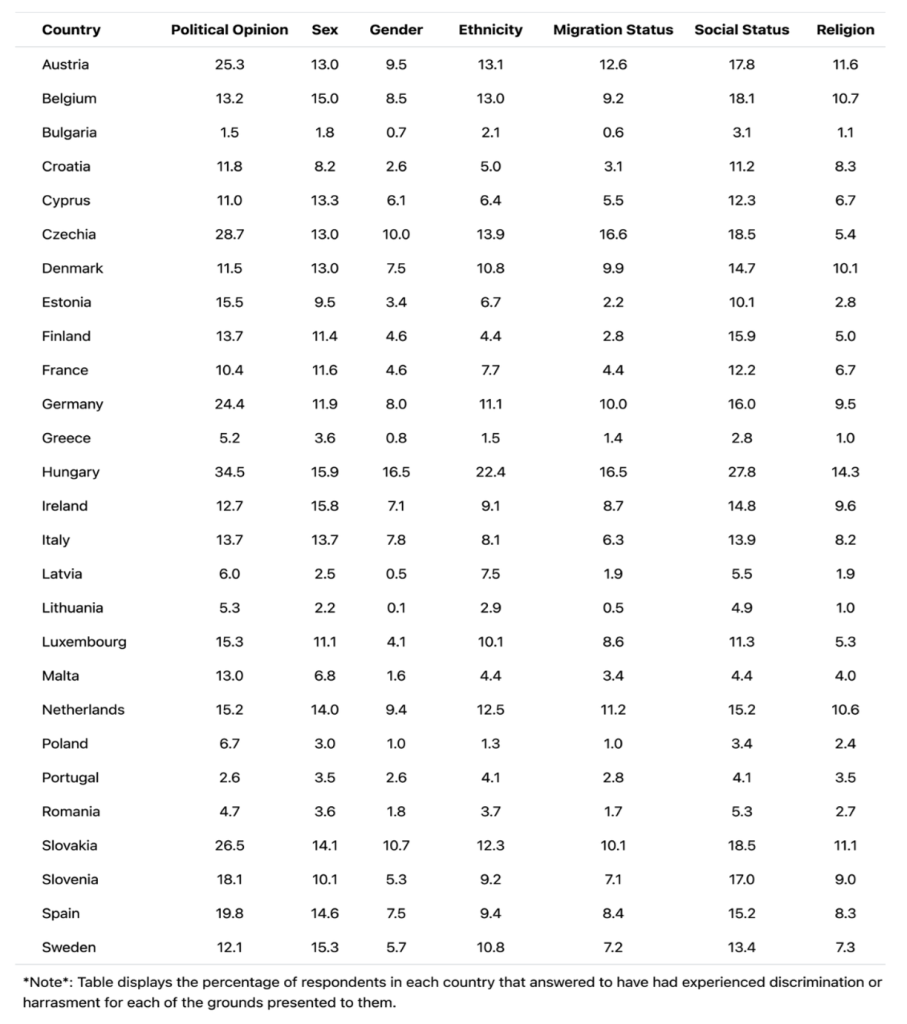

Table 1: The incidence rate of perceived discrimination by its grounds

Political discrimination in the EU

According to the World Justice Project EUROVOICES household data, discrimination is a significant challenge across the European Union. Over 25% of people faced some form of discrimination during the past year in most EU regions. Table 1 presents the incidence of self-reported discrimination across EU Member States, disaggregated by grounds for discrimination.

Political discrimination emerges as the most reported category in 13 of 27 EU countries – more than sex, ethnicity, or migration background. Rates are particularly high in Hungary (34.5%), Czechia (28.7%), Slovakia (26.5%), Austria (25.3%), and Germany (24.4%), while being especially low in Portugal (2.6%) and Bulgaria (1.5%). On average, 14.7% of people have experienced political discrimination in the EU.

These patterns suggest that political discrimination is a salient and widespread phenomenon in many European contexts. Importantly, this form of exclusion has surpassed more commonly recognized types of discrimination in a significant number of countries, indicating a shift in how individuals experience marginalization.

These descriptive findings provide a crucial empirical foundation for our analysis. They reveal the pervasiveness of political discrimination in specific European contexts and justify a deeper investigation into its consequences for political trust.

Figure 1: Trust in political institutions by experiences of political discrimination

Relationship between Trust in Institutions and Political Discrimination

The analysis reveals a consistent and significant relationship between political discrimination and lower levels of institutional trust across the European Union. Descriptive findings show a pronounced trust gap between individuals who report having experienced political discrimination or harassment (D/H) and those who have not. As illustrated in Figure 1, the median trust score among the D/H group falls well below zero, indicating general distrust, while individuals without such experiences report more neutral or positive levels of trust.

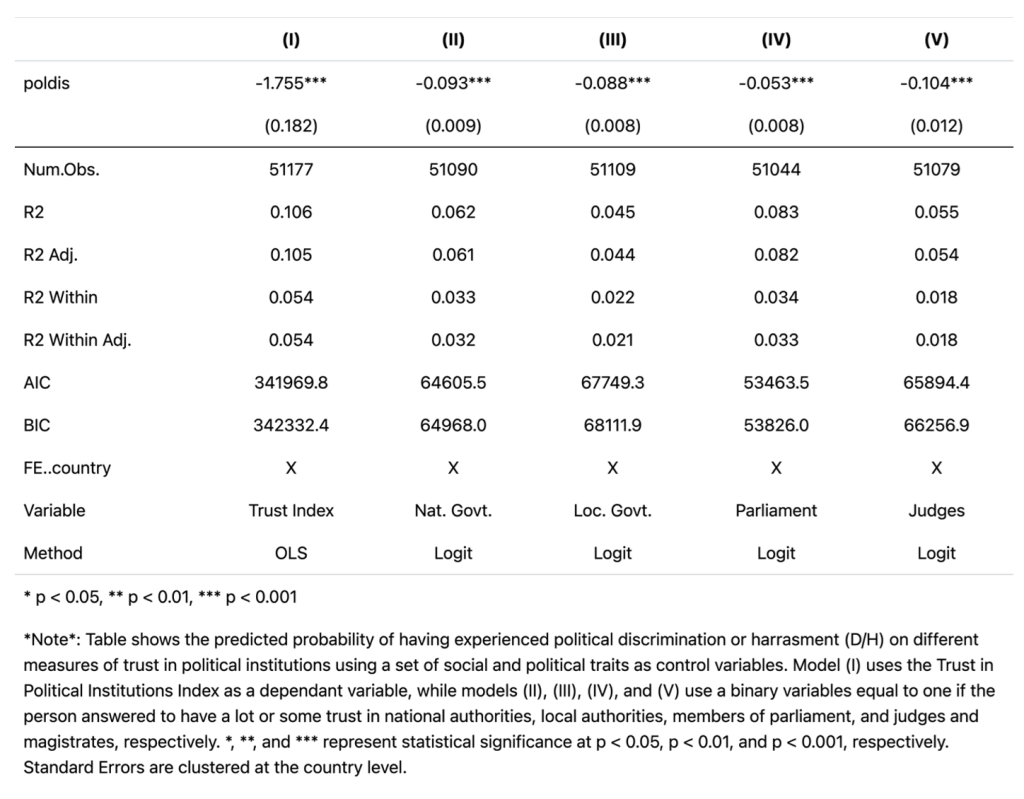

These patterns are confirmed by the regression models presented in Table 2. Individuals who experienced political discrimination exhibit a 1.755-point reduction in the overall Trust in Institutions Index, a highly significant result that supports Hypothesis 1 (H1). This effect is not limited to general attitudes: political discrimination also significantly decreases the likelihood of trusting specific institutions, including the national government, local government, parliament, and the judiciary. These results indicate that the consequences of political discrimination are not confined to a particular branch or level of government but rather reflect a systemic erosion of trust.

Table 2: Relationship between political D/H experiences and institutional trust measures

Importantly, some institutions appear more vulnerable to this decline. The largest drops in trust are observed in relation to national governments and judges and magistrates – bodies that are generally expected to uphold neutrality, legality, and procedural fairness. The fact that trust in these institutions declines so markedly following experiences of political discrimination points to a critical vulnerability: even in the absence of direct perceptions of institutional bias, the mere experience of exclusion can weaken confidence in the institutional pillars that sustain the rule of law. This erosion of trust is particularly concerning because it affects institutions responsible for ensuring accountability, safeguarding rights, and adjudicating disputes impartially.

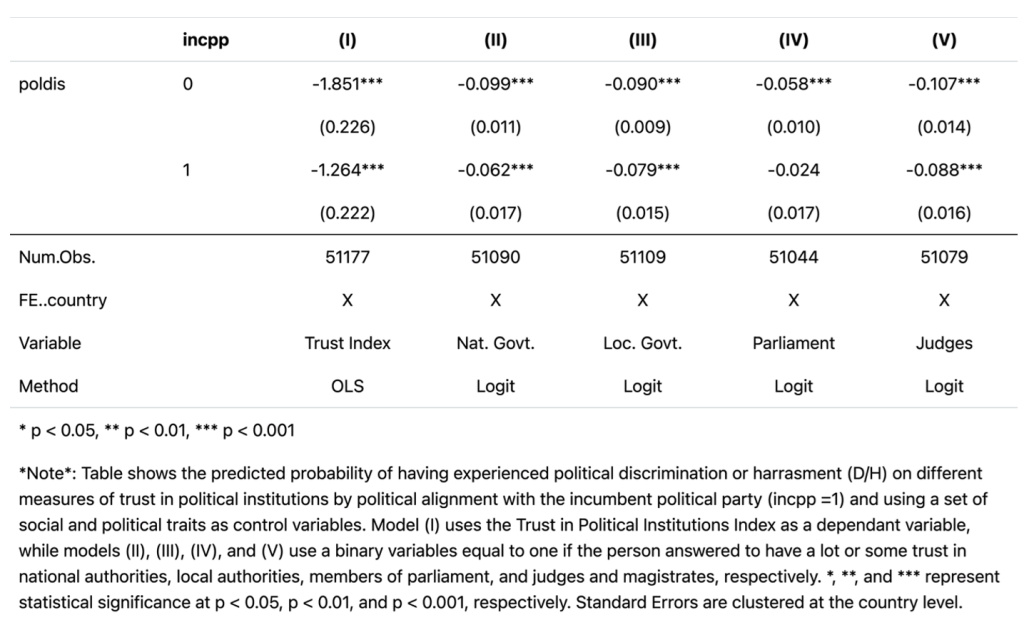

Table 3 extends this analysis by examining the moderating role of partisan alignment. Disaggregating the sample by whether respondents support the incumbent political party reveals that trust declines in both groupsfollowing experiences of political discrimination. However, the effect is consistently stronger among individuals who are not aligned with incumbent politicians and parties, suggesting a compounding effect of ideological and experiential exclusion.

Table 3: Relationship between political D/H experiences and institutional trust measures by political alignment

This asymmetry offers important insights into the nature of political trust in polarized contexts. The fact that political discrimination reduces institutional trust across the political spectrum suggests that the effect is not solely driven by partisan identity. Yet the sharper decline among opposition-aligned individuals points to a deeper erosion of perceived neutrality: institutions are increasingly seen as responsive only to the group with which each person identifies. Under these conditions, trust becomes conditional on perceived group representation, eroding the shared legitimacy of democratic institutions. This dynamic is emblematic of affective polarization, in which political identity shapes preferences and distorts perceptions of institutional fairness. These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 1b (H1b), demonstrating that the negative association between political discrimination and institutional trust is amplified among individuals embedded in polarized political environments, where political opponents are viewed as constituting a moral threat and causing institutional bias. In such contexts, political discrimination does not merely reduce trust – it accelerates the breakdown of the civic norms and institutional impartiality essential to democratic resilience.

Conclusion

This study provides robust empirical evidence that political discrimination is a significant and systemic threat to institutional trust in the European Union. Drawing on the EUROVOICES survey, we find that individuals who report having experienced political discrimination or harassment exhibit substantially lower levels of trust in both national and local institutions. Further analysis shows that the negative effect of political discrimination on institutional trust is amplified among individuals who are not aligned with the incumbent politicians or parties. This partisan asymmetry underscores the relevance of affective polarization as a moderating force: in politically divided societies, institutional trust becomes increasingly conditional on perceived group representation. Crucially, we also find that the decline in trust is especially pronounced in institutions tasked with safeguarding the rule of law – namely, national governments and the judiciary. This erosion of confidence in impartial institutions represents a deeper risk to democratic governance, as it weakens the normative belief that all citizens, regardless of political affiliation, will be treated equally under the law.

These findings signal more than a crisis of perception – they reflect a weakening of the institutional foundations that sustain democratic resilience. When trust in core institutions fractures along political lines, it erodes the common democratic ground necessary for pluralism, compromise, and accountability. In such environments, citizens may disengage from formal politics or turn towards more radical alternatives, while institutional actors themselves face declining legitimacy and capacity to mediate conflict.

Addressing the democratic costs of political discrimination requires a multidimensional policy response. First, anti-discrimination protections should be expanded to explicitly include political opinion, particularly in employment, education, and digital platforms. Second, governments and civil society actors should invest in cross-partisan dialogue mechanisms to rebuild social trust and mitigate affective polarization. Third, efforts to reinforce institutional impartiality – through independent judiciaries, transparent policymaking, and pluralistic media systems – are essential to restoring the credibility of public institutions.

Finally, democratic legitimacy depends not only on competitive elections or formal representation, but also on citizens' confidence that institutions will protect and treat their rights fairly – regardless of who holds power. In a context of growing polarization and political exclusion, rebuilding that trust is both a normative imperative and a practical necessity for the future of European democracy.

Ana María Montoya holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Duke University. She is currently the Director of Data Analytics at the World Justice Project. Her research focuses on judicial politics, public opinion, and the rule of law.

Santiago Pardo is a Senior Data Analyst at the World Justice Project. He holds a Master’s in Economics from Universidad de Los Andes. His work focuses on access to justice, human rights, and the effectiveness of the rule of law worldwide.

Natalia Rodríguez is a Senior Data Analyst at the World Justice Project. She holds a Master's degree in Economics from Universidad de Los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia). Her research interests include education, public policy, rule of law, and access to justice.

Carlos Toruño is a Senior Data Analyst at the World Justice Project. He holds an M.Sc. in Development Economics from the University of Göttingen and specializes in data science and quantitative methods for public policy analysis, including the application of quasi-experimental designs.

Photo by Mikhail Nilov

References

Anderson, C. J., & Tverdova, Y. V. (2003). Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00007

Armingeon, K., & Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. European Journal of Political Research, 53(3), 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12046

Citrin, J., & Stoker, L. (2018). Political trust in a cynical age. Annual Review of Political Science, 21, 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550

Dalton, R. J., & Wattenberg, M. P. (2000). Parties without partisans: Political change in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford University Press.

Drutman, L. (2019). Breaking the two-party doom loop: The case for multiparty democracy in America. Oxford University Press.

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D., Scheinkman, J. A., & Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554926

Holmberg, S. (2007). Partisanship reconsidered. In R. J. Dalton & H.-D. Klingemann (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political behavior (pp. 557–576). Oxford University Press.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2019). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 63(3), 590–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12487

Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2022). Trust: The key to social cohesion and growth in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter-American Development Bank. https://doi.org/10.18235/0004352

Landgraf, A. J., & Lee, Y. (2020). Dimensionality reduction for binary data through the projection of natural parameters. Journal of Multivariate Analysis, 180, 104668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmva.2020.104668

Lelkes, Y., & Westwood, S. J. (2017). The limits of partisan prejudice. The Journal of Politics, 79(2), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1086/690562

Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 475–507. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. Crown Publishing Group.

Lipset, S. M., & Rokkan, S. (1967). Party systems and voter alignments: Cross-national perspectives. Free Press.

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Nord, J., Smith, K., & Ferland, D. (2024). Populism, polarization, and political trust in the European Union. [Publisher not specified – please confirm].

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

OECD. (2024). Building trust and reinforcing democracy: Preparing the ground for renewal. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/cde997ff-en

Oskooii, K. A. R. (2016). Discrimination and participation: A multidimensional framework for understanding political behavior. Political Psychology, 37(5), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12294

Oskooii, K. A. R. (2020). The civic consequences of perceived discrimination: A resource model of participation. The Journal of Politics, 82(3), 973–989. https://doi.org/10.1086/707310

Richardson, B. (1991). European party loyalties revisited. Dartmouth Publishing.

Thomassen, J. (1976). Party identification as a cross-national concept: Its meaning in the Netherlands. In I. Budge, I. Crewe, & D. Farlie (Eds.), Party identification and beyond: Representations of voting and party competition (pp. 263–284). Wiley.

Thomassen, J., & Rosema, M. (2009). Party identification revisited. In R. J. Dalton & H.-D. Klingemann (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political behavior (pp. 218–235). Oxford University Press.

Wilkes, R., & Wu, C. (2018). Trust and minority groups. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274801.013.24