Teaching and Learning in the Age of Uncertainty: Reflections on 21st Century Pedagogy

Daniel Clausen on what we might do to help students reclaim autonomy in an age of technological revolutions.

It may be unfair to say that ours is an age of unique uncertainty. After all, those growing up during the horrific wars of the early 20th century, the Cold War era of the mid-to-late 20th century, the upheavals of the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s, the so-called “New World Disorder” of the 1990s, or the Global War on Terrorism in the 2000s might make a similar claim. Thus, when I state that ours is a time of unusual uncertainty and insecurity, perhaps I am simply rehearsing a timeless motif.

Yet, the 2020s feel like an unusual time in terms of the quality and quantity of our uncertainties and fears. The old threats of nuclear war, environmental catastrophe, pandemics, interstate wars, and state breakdown are now subject to the processes of speeding up, compounding, and cross-pollinating. Even worse, national crises, such as pandemics, have become battlegrounds of partisan politics rather than motivations for overcoming narrow affiliations (see Clinton et al., 2021; Milosh et al., 2021).

An unwieldy atmosphere of algorithm-enhanced social media platforms has incentivized leaders to bypass institutions and expertise in favor of exploiting divisions and outrage, making much-needed global cooperation on collective problems more difficult (Azzimonti & Fernandes, 2023; Kubin & von Sikorski, 2021). For teachers, even the simple job of informing students is made more difficult by the volume and virality of misinformation.

In such an environment of uncertainty, how can educators and researchers cope?

Although I cannot offer any definitive answers that will leave all readers properly sheltered from 21st-century calamities, I have identified several (hopefully productive) avenues of inquiry. In particular, I have settled on four ideas that appear fruitful: embracing the liberal arts; cultivating a diverse analytical toolbox; de-21st-centurizing our thinking (to an extent); and embracing radical experiments in digital detoxification.

IR education as a liberal art. In a chapter for the edited volume Signature Pedagogies in International Relations, Lisa Macleod (2021) makes the case for a version of International Relations (IR) that is embedded in the liberal arts. The idea is that students majoring in IR should learn the broader skills of critical thinking, communication skills, and civic responsibility. Her chapter also makes the case for training students who can engage with thinkers across disciplines. In my own article for EFL Magazine, I furthered Macleod’s case by arguing that the liberal arts is best suited for nurturing human skills like empathy, collaboration, and integrating moral aspects of education (Clausen, 2021, September 15). My intuition is that the movement toward embracing the liberal arts is already in progress and will soon extend from the humanities and social sciences into more technical fields, as technology reduces the barriers between specialists and non-specialists. As this shift occurs, educators of all stripes will need to become more fluent in the language of “student-centered learning,” “challenge-based learning,” and “project-based learning” (Clausen, 2016, September 1).

A diverse analytical toolbox. As someone who has traversed several academic domains—doing their undergraduate studies in English literature and later transitioning into IR—I feel comfortable using a diverse analytical toolbox (Clausen, 2024). Whenever I encounter a new problem, I start with simple methods, typically nothing more than scratch paper and a pencil, and work to greater complexity.

With the continuous improvements in artificial intelligence (AI), it is entirely possible that what was once esoteric and out of reach for young researchers will become commonplace, maybe even mundane. As writing literature reviews, creating research designs, and conducting statistical analysis become more automated, researchers will have the freedom to become more exotic in their research tastes. The results may produce some academic work that feels absurd—similar to what can be seen in the strangest of postmodern art or in the epidemic of AI slop that has consumed the internet (Roozenbeek et al., 2025, May 28)—however, it may also lead to finer degrees of research artistry.

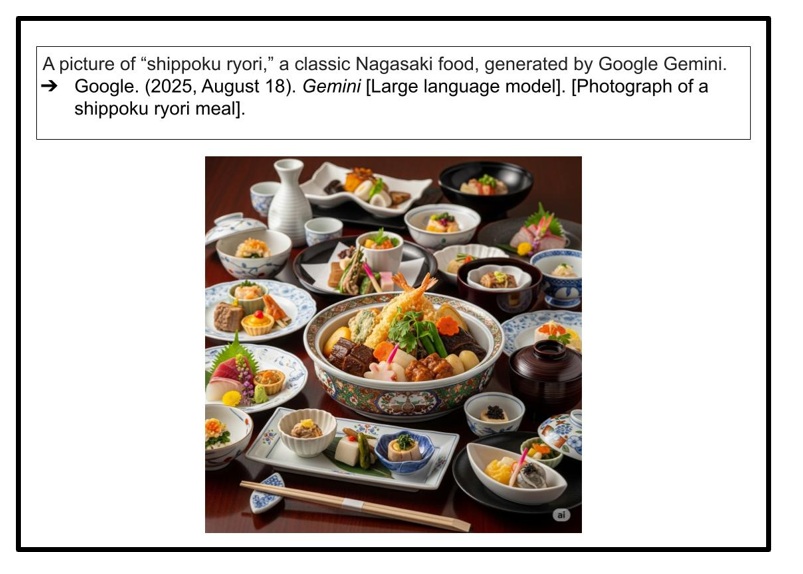

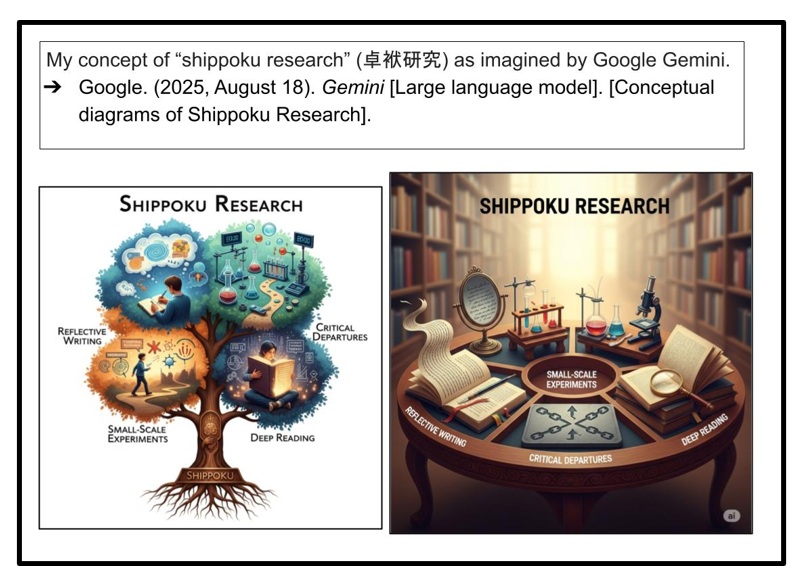

Recently I have been experimenting with something I call “shippoku research”— which I have named after the traditional Nagasaki dish that contains various foods from different cultures.

Many of the problems of the 21st century may require an approach with similar types of syncretic whimsy, starting simple and then growing into methods that combine different skills across disciplines. In some cases, generative AI will simplify this work. In other cases, the simplification of this process will be the problem—compromising our cognitive autonomy and weakening our ability to devise solutions without the aid of machines. For this reason, I advise researchers and students to experiment with new AI tools cautiously…and to avoid becoming addicted.

Critical Departure 1—De-21st-Centurizing Our Thinking. Perhaps it is simply my age—the graying ideas of someone who once had to look up information in a thick yellow phonebook—but I still find value in simple methods. Recently in my classes, to get around the ease and comfort of smartphones and generative AI, I make my students do old-fashioned in-class, pencil-and-paper writing. My best guess is that similar efforts might be needed to get students reading physical books again. To be fair, there is a fair amount of research that rejects this trend—for example, research that looks at the value of multiliteracy (literacy beyond the printed page) (Cope & Kalantzis, 2013; Mirra & Garcia, 2021). However, my instinct tells me that while the generation of tomorrow will need digital skills to thrive, they will also need habits—such as mental discipline and rugged intellectual independence—that will protect them from algorithmic addictions and deluges of misinformation. In building these resiliencies, it might be productive to temporarily shelve more progressive forms of learning in favor of the raw discipline of reading, writing, and retaining key information.

Critical Departure 2—Walden 2025. In the spirit of critical departures, let us depart from the beaten path even further—into the literary endeavors of the 19th-century American essayist Henry David Thoreau. In his seminal literary work, Walden, Thoreau (1854) details his experience living in nature for a little over two years, experiencing life in all its dynamic simplicity. Thoreau’s Walden was an early literary work that addressed humanity’s need to reclaim personal autonomy outside of corrupting societal systems—in Thoreau’s case, materialism, conformity, and the (over)division of labor. The essay was as much about becoming ethically clean as it was about regaining personal autonomy and competence.

Perhaps today we need a similar rugged intellectual revolution. Beyond merely collecting student phones before class (plus digital watches, digital glasses, and everything else that will soon be digitally connected), what can we do to help students reclaim some of the autonomy that Thoreau was seeking? Perhaps we might ask students to go out into the field and take notes on pen and paper and not rely too heavily on their digital devices. We might also emphasize and value more “traditional” (even “Fordist”) educational activities and behaviors: showing up to class on time, being prepared, and retaining key knowledge.

This might seemingly contradict my earlier suggestion of leaning into the liberal arts aspects of education; however, when used together appropriately, I believe the varying approaches can be complementary.

If such a suggestion seems too radical a departure, perhaps it shows how fast we have changed in the past few years and how much autonomy we have already lost to technology. If going “full Walden” seems like a bridge too far, then perhaps it is a sign that such digital-detox interventions are needed now more than ever.

Daniel Clausen is a full-time lecturer at Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies. He is a graduate of Florida International University’s Ph.D. program in International Relations. His research has been published in Asian Politics & Policy, e-International Relations, The Diplomatic Courier and Global Policy, among other journals and magazines.

Works Cited

Azzimonti, M., & Fernandes, M. (2023). Social media networks, fake news, and polarization. European Journal of Political Economy, 76, 102256.

Clausen, D. (2016, September 1). Towards a ‘challenge-driven’ international relations education? E-International Relations.

Clausen, D. (2021, September 15). The future of English language teaching is liberal arts. EFL Magazine: The Magazine for English Language Teachers.

Clausen, D. (2024). Building a 21st Century Analytical Toolbox: Advice, Hesitations, and Deviations. The Journal of Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies. Volume 28 (December). 59-68.

Clinton, J., Cohen, J., Lapinski, J., & Trussler, M. (2021). Partisan pandemic: How partisanship and public health concerns affect individuals’ social mobility during COVID-19. Science Advances, 7(2).

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2013). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. In Framing languages and literacies (pp. 105-135). Routledge.

Google. (2025, August 18). Gemini [Large language model]. [Conceptual diagrams of Shippoku Research].

Google. (2025, August 18). Gemini [Large language model]. [Photograph of a shippoku ryori meal].

Kubin, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(3), 188–206.

Macleod, L. (2021). Teaching international relations as a liberal art. In J. Lüdert (Ed.), Signature Pedagogies in International Relations (pp. 16–27). e-International Relations.

Milosh, M., Painter, M., Sonin, K., Van Dijcke, D., & Wright, A. L. (2021). Unmasking partisanship: Polarization undermines public response to collective risk. Journal of Public Economics, 204, 104538.

Mirra, N., & Garcia, A. (2021). In search of the meaning and purpose of 21st‐century literacy learning: a critical review of research and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(3), 463-496.

Roozenbeek, J., Van Der Linden, S., & Kyrychenko, Y. (2025, May 28). What is AI slop? Why you are seeing more fake photos and videos in your social media feeds. The Conversation.

Thoreau, H. D. (1854). Walden; or, Life in the woods. Ticknor and Fields.