Decolonizing Education Systems: Integrating Indigenous Forms of Education

This is the thirteenth chapter in a forthcoming e-book, entitled 'Decolonial Education and Youth Aspirations'. Chisom Okafor and Bente Fatema explore ways to integrate indigenous forms of learning and teaching into Eurocentric models.

Eurocentric models have long dominated the education models that are prevalent today. These models were imposed upon the nations of the global south and global east through colonial legacies and the influence of international organisations (Naidoo and Muthukrishna, 2014). This has resulted in the domination of Western epistemologies, marginalising indigenous ways of knowing, rooted in the cultural and spiritual traditions of the Global South. Hence, to decolonise education systems and to ensure that terms like "education" and "knowledge" align with the realities and needs of local communities, it is essential to think beyond the existing Eurocentric systems of education.

One way to achieve this is to explore and integrate indigenous forms of learning and teaching. This involves a deep examination of indigenous cultures as well as the learning and teaching practices they embody (Morrow, 2008; Mutekwe, 2014). The goal of this integration is twofold: (a) empowering students to challenge dominant narratives and power structures, and (b) fostering critical pedagogy among learners so that they become active participants in post-colonial democratic societies.

Eurocentric Education Models

Eurocentric educational models are frameworks that seek to influence students' perspectives by prioritising a Eurocentric worldview. This approach often implies that non-European cultures, values, and viewpoints are less valuable or significant, creating a mindset that all non-Eurocentric things are inferior (Barkaskas and Gladwin, 2021).

The educational system present in the global South is traced back to colonial times, when the colonial system saw the need to inculcate a form of education that would train Africans to take up the lowest ranks in the administration of the capitalist system (Rodney, 1972). It also was discriminatory in its approach, going only for a select few, unlike the inclusive nature of learning that the context was used to (Rodney, 1972; Njoku, 1992). This approach to learning sought to make learners submissive to the European system and feel disconnected and less confident of their own culture and identity. This mode of education that sought to train students to become workers in the colonial administration of the West still has a strong hold on the modes of education present in today's teaching in countries in the global South and East.

The exploitation and dehumanisation of colonialism led to limited funds going into education in these regions. This streamlined the ability of the educational sector to transcend beyond the limited nature of the educational framework introduced into the context. These modes of learning sought to replace existing Indigenous forms of learning that were contextually relevant to its peoples (Rodney, 1972). This, in turn, alienated students, limited their understanding of global cultures, and reinforced stereotypes and biases among them. The praxis of competition, grading systems, and standardised assessments can lead to isolation and disconnection (Barkaskas and Gladwin, 2021), which is particularly detrimental for learners with disabilities or international origin who may already feel out of place in unfamiliar environments.

Indigenous forms of Education

In today's classrooms, the wide variety of student backgrounds and needs heightens the importance of recognising the limitation and potential harm of a Eurocentric educational model and adopting a more inclusive, decolonised approach to education that makes the learning environment more relevant, equitable, and enriching for all students. One way this can be achieved is by integrating indigenous forms of teaching and learning that are contextually relevant to its peoples.

Indigenous forms of education refer to culturally relevant pedagogies that are rooted in the histories, languages, values, and practices of Indigenous peoples. The essence of indigenous forms of education is derived from indigenous societies. Indigenous societies were built on a communal transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next, which ensured that an understanding of the context and what was relevant to the community's growth was learnt and mastered (McGovern, 2000). The education practices of indigenous societies sought to build all-round learners mentally, emotionally, and spiritually in a way that allowed them to thrive within their context (Rodney, 1972). These indigenous, non-European, and non-Anglo-Saxon ways of education have been a cornerstone of various indigenous societies and have thrived for centuries.

Adopting Indigenous educational practices can be a crucial step towards decolonising education (UNESCO, 2004). It can play an important role in how learning takes place in diverse classrooms through more integrated learning (Battiste and Henderson, 2009). To elaborate, Indigenous forms of education respect and celebrate the diversity of people and ideas and hence can create a more inclusive and comprehensive educational experience for students where all students feel seen, understood, and valued. It allows students to appreciate and embrace diverse cultural perspectives, thus fostering a sense of identity and inclusion among students from various backgrounds in the classroom. It also set the stage for an inclusive space where all students can see themselves and their communities reflected in the curriculum. Embracing inclusive epistemologies will also help enable them to cultivate empathy, critical thinking, and a deeper understanding of global interconnections—qualities that are increasingly important in today’s interconnected world.

This chapterfocuses on two Indigenous forms of education from Nigeria and Bangladesh; exploring the contributions of these indigenous systems in the field of business and in the general educational system to consider how they can be integrated for a more inclusive curriculum.

Case Studies of Indigenous Learning and Teaching Practices

Examination of the unique aspects of Igbo culture and its educational practices in Nigeria.

An example of an Indigenous educational system can be found among the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria. For centuries before, and after the impact of colonialism and imperialism that sought to transform how individuals in these regions were educated, there existed an indigenous form of knowledge transfer that ensured the sustenance of ways of life and trade within their communities and from one generation to another. This practice is defined by scholars as the Igbo apprenticeship system (Njoku, 1992; Orji, 2012), an Indigenous Igbo business incubator (Ekekwe, 2021), or an Indigenous form of knowledge transfer (Adeola, 2020).

This unique practice, culturally known as Imu-ahia, became popular after the devastating impact of the Nigerian civil war of 1967. The British government brought together the northern, western, and eastern regions to become one country, and after independence in 1960, the eastern region wanted to exit this political and geographical arrangement. However, it was met with war that killed over 3 million Igbo people and destroyed livelihoods and infrastructure.

To ensure their survival, they started to migrate to different parts of the country, engaging in various trades, crafts, businesses, and so on, but they did something interesting. For every trade or business that was set up, they would take up young people from their clans and communities within the secondary schooling age and give them real-life training of their skills, customer relationships, trade, financial management, and so on. After 5 to 6 years of this rigorous training, the initial business or coach will divide their business capital and market share with this new trainee or apprentice to enable them to replicate the same practice on their own. This robust investment in human development brought about the restoration of the devastated group back to its previous level within 2 years (Igwe, 2020).

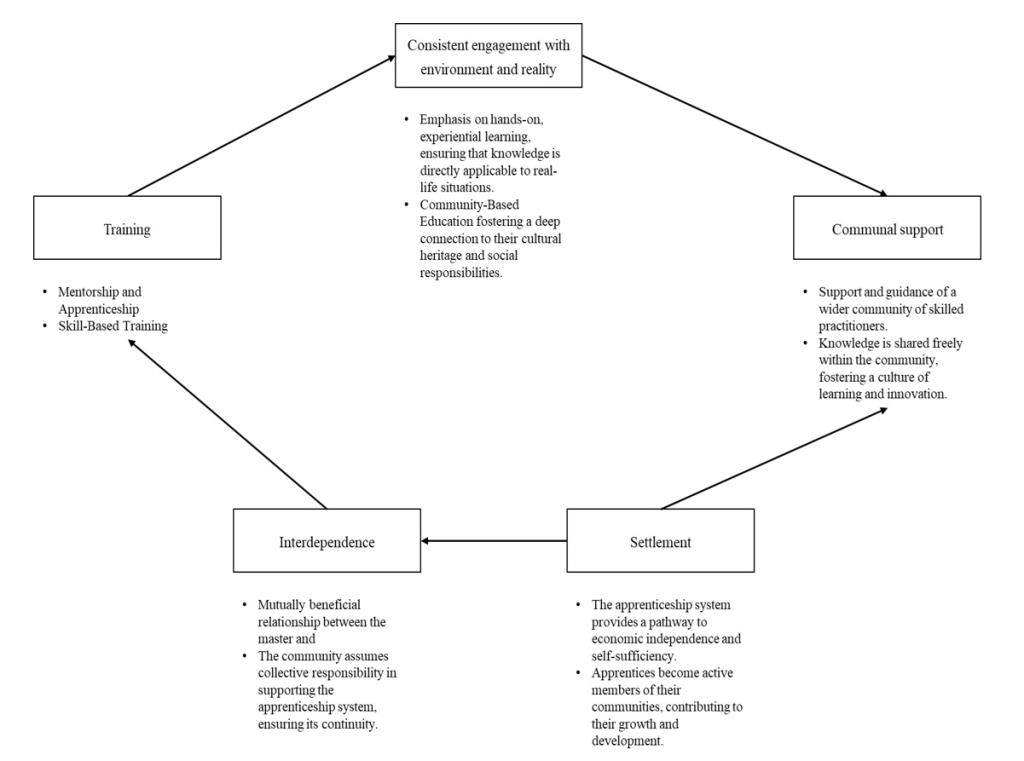

Figure 1: Indigenous Igbo

Unlike the conventional form of education that starts from fragmented courses at the secondary school level, the practice works in reverse, offering a real-life business from which relevant courses are then integrated. This enabled a system of incubating and training the potentials of these youths that morphed replicas of their trade all over the country (Ndigwe, 2020). Research by Neuwirth (2018) showed a sample of this practice in the Alaba market in Lagos, Nigeria, where that market alone, with over 10,000 separate businesses that are products of this Indigenous platform, makes over 4 billion dollars in revenue annually. The culture or way of thinking behind this practice is one of a communal spirit that, contrary to the Western mindset of every man for themselves in education, holds instead the mantra “No man left behind,” which in the local dialect is “Onye Aghala Nwanne Ya.”.

Colonial systems of education prevalent in the Nigerian context sought to diminish the indigenes to the level of low cadre staff in the establishments that in turn sought to dehumanise them. The legacies of this Eurocentric approach to education still exist in Nigeria and other global South countries, stifling innovation and outside-the-box thinking. The Indigenous Igbo practice decolonises education by establishing a mindset of self-worth and responsibility to the community, creating an interdependent network that enables its peoples to thrive regardless of the terrain.

Examining the Role of Madrasah Education in Community Development in Bangladesh

The madrasah system is an educational framework that focuses on theological ways of learning and teaching. It aims to equip students with the knowledge and skills necessary to meet both social and religious expectations. It helps students gain a deeper understanding of their faith and empowers them to apply this knowledge for the betterment of their lives as well as those of others in the wider society.

Madrasah's system was established centuries before western universities, having roots in Bengal during the Sultani era (1210–1576) and saw significant development during the Mughal Empire (1526–1761) (Karim, 2018). In that period, the curriculum of madrasah was limited to various religious and philosophical instructions. It was only in the 21st century that it was combined with other subjects from the humanities and social sciences to foster critical thinking and societal awareness among Madrasah students. At present, there are around 2.75 million students enrolled in different levels of Madrasah education (Rahman, 2024). According to the latest consolidated report, there are approximately 15,000 state-surveillance institutions and 48,000 independent madrasah educational institutions in Bangladesh (Asadullah and Chaudhury, 2016). These institutions can be classified according to their program duration, with Dakhil offering a six-year program, Ebtidai a five-year program, and Alim, Fazil, and Kamil each offering two-year programs (Karim, 2018). While they have different curricula and practices (Abdalla et al., 2004), what brings them together is their ideological pedigree practices around their community.

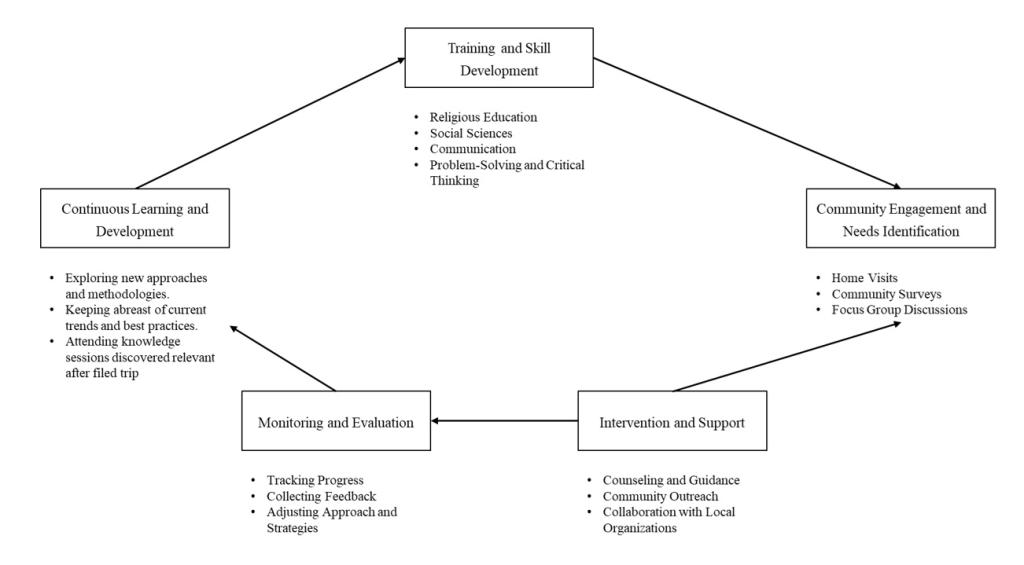

Figure 2: The Social Service Praxis of Madrasah Education

The Madrasahs system of education is built upon communal knowledge transfer practices within indigenous societies where the understanding of context and community-relevant knowledge are carefully preserved and passed down across generations (Sali and Marasigan, 2020; Suhardi et al., 2020). There are two pedagogies of Madrasah education that can help us understand how it has contributed to the decolonisation of educational systems in Bangladesh. To begin with, the Madrasah system necessitates its students to enter society and apply learnt principles in real-world contexts. The aim of this practice is to foster a sense of social responsibility and civic engagement among its students. As part of this process, graduates visit families and households, build rapport, establish connections, and attempt to gain insights into the everyday challenges faced by individuals and families. Drawing from their faith-based learnings, they actively seek to address these challenges, particularly those stemming from behavioural issues (e.g., domestic violence, monogamy, gender inequality, etc.). They provide support and counselling and conduct follow-ups to ensure that the assistance offered is effective and continues to meet the needs of the community. This hands-on approach not only allows them an opportunity to translate their learnings into action in meaningful ways but also fosters a sense of responsibility and commitment to their communities.

One of their noteworthy initiatives that has garnered attention is their effort to bridge the communication gap of mute people. For mute people, the only way they can communicate is through sign language, but learning the formal sign language can be challenging for people who live from hand to mouth. Given this, a group of Madrasah people introduced a local sign language that was similar and way simpler compared to standard sign language. They also included part of natural linguistics in their crafted sign language so that it is easy for common people to express their thoughts without being constrained by a fixed set of coded signs. This is one of many examples of social services that these individuals provide, primarily because their learning curriculum requires them to understand the people around them and their challenges, enabling them to address real-life problems effectively. This practical application of learnt principles is a wonderful example of how educational systems can be decolonised to promote inclusivity and empower individuals to contribute positively to their societies.

Secondly, the Madrasah system also organises yearly collaborative initiatives, where in-house students form teams with local community members. The goal of such team formation is twofold: first, to reinforce their religious teachings through the exchange of knowledge between experts and those with less expertise, and second, to address prevailing problems within the community and society. These students set aside about a month from their educational curriculum to dedicate themselves to these efforts. To achieve the knowledge exchange goals, they visit different religious centres both within and outside their area, investing mental and physical effort to share faith-based knowledge. In parallel, to tackle community challenges, they engage in various outreach activities, such as organising workshops, conducting surveys to identify local needs, and collaborating with community leaders to implement effective solutions. And so, when Bangladesh was struck by a massive flood in August 2024, which left millions stranded and displaced from their homes (UNICEF, 2024), they did not hesitate to step in and offer support. They took charge, leading efforts from fundraising to executing life-saving rescue, relief, and rehabilitation initiatives (Mahmud, 2024). They organized task forces with local populations, NGOs, and state support, uniting their efforts to plan and implement life-saving initiatives with coordination and determination (Bangla Vision News, 2024). Their demonstration of leadership and commitment in the face of crisis showed what engineering diplomacy truly means in practice. While their efforts saved countless lives and brought many from water to safety, this hands-on involvement also taught them important lessons of leadership, organization, and collaboration, all while making a lasting, tangible impact in their communities. Such community-oriented and pragmatic practices, exemplified by the Madrasah system, provide a powerful framework for educators seeking to decolonise the education system. By emphasising community engagement, practical application of knowledge, and the development of essential life skills, educators can create more inclusive, relevant, and impactful educational experiences that empower students to contribute positively to their societies.

Lessons Learned: Takeaways from Indigenous Forms of Learning and Teaching

The insights gained from the case of Igbo and Madrasah indicate that indigenous forms of education go beyond the four walls of the classroom and integrate the communal nature of learning where students learn from their community, their society, their peers, and the wisdom of their elders. Unlike the Eurocentric form of education, which holds conventional internships and industry collaboration as important, indigenous forms of education instead focus on community engagement and experiential learning opportunities that are deeply rooted in local contexts. It relies on the interdependencies of individuals, communities, businesses, and the entire learning process that leads to faster and more sustainable results.

For instance, the knowledge transfer system of the Igbos is built on communal support, where the result of teamwork is not tied to the identity of the individual but serves as a platform for increased tenacity and engagement with reality (Orji, 2012). When students under this system face setbacks, it is an opportunity for them to build on those mistakes without fear of it negatively impacting their performance records. The ability to depend on fellow learners, coaches, and the community is prioritised, unlike conventional Eurocentric methods that seek to isolate and broaden inequalities in the classroom. This inclusive approach allows the students to shape their future, provides space for creativity and innovation, and ensures learners become active participants in post-colonial democratic societies.

Likewise, the social service axis of Madrasah education created a framework where students assume social responsibility and perform activities around societal relevance. This integration of knowledge and practice provides the students an opportunity to apply their learnt knowledge to solve prevailing problems in society. This, in turn, instils a sense of responsibility and accountability among students. These skills are crucial for students to navigate in a rapidly changing global landscape, where addressing emerging societal needs is increasingly important. Moreover, it also teaches students how to engage with their local populations, foster teamwork, and develop effective solutions, thus empowering them to become active contributors to society. On the contrary, it provides society with ‘solution providers’ who offer tailored, effective responses to societal problems, enhancing the quality of life for those around them. These solution providers are not just any graduates but are people who are aware of and responsive to the needs of their communities. In the long run, their social awareness propels them to take more active participation in local governance and community initiatives, fostering a healthier democratic environment.

Both the Igbo apprenticeship system and the social service axis of Madrasah education are built on the idea that education is not solely an individual endeavour but a collective responsibility. Both education systems are built upon local elements of cultural, social, and economic contexts, serving as powerful models for decolonising education.

Strategies for incorporating indigenous knowledge into contemporary educational frameworks

The consideration of integrating indigenous lenses into education serves as the first step to decolonise education in a way that deconstructs neo-colonial models and can liberate learners towards new ways of thinking and appreciation of diverse ways of thinking, cultures, and practices. The first step to achieve this would be to give equal importance to indigenous histories, worldviews, contributions, and practices when teaching history, science, and literature. To ensure that the students have access to indigenous knowledge, indigenous elders, cultural practitioners, and community leaders should also be stood in front of students, side-by-side with industry professionals as leaders and mentors.

Moreover, educators need to think beyond conventional, fixed knowledge-based curricula and include experiential and place-based learning approaches that allow students to learn progressively as they engage with real-world applications. However, to achieve this, educators will also need to be trained on indigenous perspectives, cultural competency, and sensitivity. Hence, all stakeholders in the education system, including school management and policymakers, must come together to create a more respectful and inclusive learning environment that values indigenous knowledge as a key part of a well-rounded education and wellbeing.

Both Chisom Okafor and Bente Fatema are PhD Candidates at Queen Mary University of London. Find out more about Chisom Okafor here and more about Bente Fatema here.

Photo by Erique Erufu Onojoserio