Refections on (Iranian) Nationalism

Ali Ansari argues that patriotism requires freedom.

Nationalism is a peculiar ideology. Depending on the context, it elicits praise or condemnation, scrutiny or acceptance, in almost equal measure. It is the only ideology that liberally minded people are inclined to accept in some circumstances while pouring scorn on it in others. As someone who lived through the high tide of Scottish nationalism I was always puzzled by how the profusion of flag waving north of the border was a legitimate expression of national identity while any such expression south of the border drew swift condemnation and ridicule.

In sum, our approach to ‘nationalism’, often casually deployed and ill defined, is heavily shaped by our preconceptions, and our engagement with our sources will reflect the prejudice we bring to our analysis. This prejudice will often be affected by the fact that we harbour ‘nationalist’ sentiments ourselves though ‘we’ are patriots (to borrow from Orwell’s useful distinction) while ‘others’ are nationalists.1 This sense of thinking through an ideology to critique or indeed express an ideological sentiment is a methodological problem that is rarely grappled with, not least in the non-European world, where ‘nationalism’, far from being regarded as a problem, is valued as an important asset in the fight against ‘imperialism’.

We, in the West, are therefore unusually tolerant of non-Europeans taking pride in their ‘nation’, not least in its apparent longevity, often indulging in an expression of ‘blood and soil’ primordialism that has long been dismissed in scholarly circles as dangerously nonsensical. Not only does it argue for permanence, but also in particular characteristics that render the people in question, special and by extension, superior.

Iranian nationalism, naturally, has idiosyncrasies of its own, not least in its origins and development. Unlike many non-European nationalisms, it was more of a response than a reaction to European imperialism. The European challenge crystallised nationalist ideology, but Iranian identity had deeper roots and could draw on a reservoir of ideas that far predated any encounter with Europe. What Europe and broader trends in modernity enabled, was the translation of an elite phenomenon into something more popular: what, to paraphrase Antony D Smith, we may characterise as the transition from lateral to demotic ethnie (identity), and ultimately nationalism.

But even here one must take care to be specific. A passion for identity does not always translate into political action, and indignantly huffing and puffing about national greatness and rights, is not the same as a patient ‘patriotic’ pragmatism. A shared identity and pride in that identity is distinct from nationalism - a political act - for which ‘patriotism’ can be considered its better nature. Many of Iran’s earliest ideologues of nationalism understood this, seeking to move away from the politics of grievance (‘negative’ nationalism) towards patriotism (positive/cosmopolitan nationalism), and looking askance at some of the less savoury aspects of racial nationalism that were emerging in the European world.

By and large, the leading lights of Iranian nationalist thought were wary of anything that purported to show some sort of racial continuity, preferring instead to focus on language (Persian), history and culture, as the ties that bound. And while they were keen to stress continuities of identity - a common cultural thread - they adopted a solidly Burkean view that tradition enabled change and did not preclude it. In this sense, Iranian ideologues drew their inspiration from British thinkers who regarded their own ‘nation’ as an agglomeration of communities - or community of communities to coin a current phrase. For them ‘nationalism’, and a love of country was thus akin to Orwell’s understanding of patriotism.

A significant distinction from the British experience however was the nature of the development. It was generally understood that European nationalisms had been cultivated over decades if not centuries, and had been nurtured from the ground up. The process might be encouraged but it was neither rushed nor imposed, and regular conflict had honed identities. In Iran by contrast, time was of the essence. If the country was to develop, one had to cultivate a sense of national commitment - patriotism - and the state had to encourage it with a sense of urgency. This gave the whole exercise a top down feel, an imposition that some resented.

But as key thinkers understood, a constructive commitment to the nation required freedom, or at least a measure of it. If you wanted people to feel politically committed they needed to feel part of the whole, stakeholders engaged in some sort of social contract. Contrary to general belief, this is not a wholly alien concept to Iranian political thought, but a succession of states, for better and increasingly worse, viewed with deep distaste, any sort of partnership with wider society. In this concept of nationalism, the Iranians themselves were to be kept at arms length. This was Iranian nationalism without the Iranians, a nationalism which buried the individual so deep in the body of the (nation) state, it effectively excluded it. As one of the foremost ideologues of Iranian nationalism, Hasan Taqizadeh, lamented,

Real patriotism [nationalism] is built on the foundations of freedom and justice. Imposed nationalism cannot take root.2

What emerged was a performative nationalism - as opposed to ‘real patriotism’ - which cultivated pride, demanded loyalty, but eschewed political participation beyond what the State, and its rulers demanded. A strangely emasculated nationalism in which an Iranian might profess a passionate commitment to an idea of Iran without any sense of practical commitment. Here was nationalism as a signifier of loyalty, and the more irrational the profession of faith, the greater the indication of that loyalty.

Among Iranians this is often expressed in absurd primordialist claims about the eternal nature of the nation. Islamic Revolutionaries were keen to berate the last Shah for his claim that Iran enjoyed 2500 years of continuous history, notably his suggestion of some sort of monarchical thread. One might make a claim for cultural continuity, but history clearly tells us that there is no political continuity. Not that facts ever get in the way of an ideology.

Few have had any problem with the notion of ‘national’ longevity, and if anything they criticise the Shah for truncating the length. Two and half thousand years? Seven thousand years seems to be the current favourite among officials, while even opposition figures are apt to tell Western journalists that Iran has been ‘an organic nation for more than 5,000 years’.

The belief that Iran is ‘the oldest seat of dominion’ enjoys a lengthy pedigree and reflects the fact that the Iranians retained their own distinct creation myth.3 But it is remarkable how developments in the discipline of history, far from debunking the myths, have encouraged enthusiastic nationalists to pin down some sort of measurement for this aspiration.

Quite apart from the obvious question of what it meant to be ‘Iranian’ in the past, the scholarly consensus is that the Iranian tribes did not settle, what is now called the Iranian plateau, until late in the 2nd millennium BC. Still these are an improvement on the highly enthusiastic ‘nationalist’ who in the 1920s, having patiently calculated the length of the reigns of all the kings in the Persian Book of Kings (Shahnameh), solemnly pronounced that the Iranian kingdom was 10,001,010,908,314 years old. A frustrated Taqizadeh, who was already dismissive of the widespread belief in 6000 years of recorded history, bluntly pointed out that it was unlikely that the Iranian nation was twice as old as the planet.

These frustrations should nonetheless not disguise the fact that the patient work of the founding ideologues did lay the foundations of the passionate sentiments that we hear regularly today, and it was these passions that fuelled and drove much of the modernisation that took place under the Pahlavi monarchy (1926-79). Whatever differences people may have had with the politics of the day, a determination to contribute was paramount in people’s minds and few would have considered migrating.

But whereas in the early years of the 20th Century it might have been possible to have had an elite led process, effectively imposing an idea upon a reluctant populace, with the dramatic expansion of education and the growth in political consciousness, this became difficult to sustain. By the second half of the 20th Century the incongruity of a state ideology of nationalism that kept the people themselves at arms length, was increasingly apparent and even regime loyalists found Mohammad Reza Shah’s assertion in 1975, that those who did not join the ‘official’ political party, could take their passports and leave, highly offensive.

The Islamic Revolution offered a temporary respite, and for a brief period, participation widened. But freedom, in any real sense, lay far over the horizon. Nationalism in any case was now being denigrated as a Western invention that served only to divide the Islamic community. If there was a nation, then it was the nation of Islam that mattered. Such revolutionary purities were not to last long - the Iran-Iraq war saw to that - but nationalism no longer had the legitimacy it had enjoyed, and the new revolutionary elite saw it in even more instrumentalist terms. It was to be a litmus test of loyalty for those who were regarded as insufficiently pious to be part of the increasingly restricted inner circle. And as before, the more extraordinary the claims the better.

On occasion, elements of the diaspora can also exhibit acute cases of this emasculated nationalism in action. If the Shah told the dissatisfied to leave, the Islamic Republic encouraged them to do so. But if the Shah regarded those who might take up the offer as unpatriotic, the Islamic Republic viewed them with cynical pragmatism. They could be the very best type of emasculated nationalist, passionate and unthreatening, disconnected from their homeland but often desperate to make that connection. Absence after all makes the heart grow fonder.

The most enthusiastic and unreflective would make the very best type - boutique nationalists - championing Iran's ‘rights’ to enrich uranium, lambasting the West for its historic hypocrisy, while rarely paying much attention to the details of domestic repression and never having to pay the costs of the ideology they espouse. Those Iranians abroad who endorse the ‘resistance’ against the West, from the freedom of the West, should take note that the costs of ‘making Iran great again’ are born by Iranians in Iran, who have no such freedom of expression.

There is alas nothing new in this. Taqizadeh, writing in the 1920s, lambasted such people as ‘vatan-chi’, professional nationalists. Emasculated - performative - nationalism is at heart the consequence of authoritarianism and paranoid states, where freedom of thought and expression are in short supply. Ambiguity rules, convictions are disguised, and self preservation is the priority. You neither say what you mean nor mean what you say. Contradictions are rife and we are faced with what the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci called ‘contradictory consciousness’, writ large4.

The seeds sown by Taqizadeh, and his contemporaries, have been sown deep in the body politic. Much of the nationalist sentiment we hear today is the product of the foundations laid a century ago though the early ideologues would find themselves disappointed with the quality of the product. Even so, it is testament to their work, that devotion to the nation is regularly distinguished from loyalty to the State. There are, to be sure, some determined patriots, stubbornly fighting (often at great cost to their personal liberty) the good fight and speaking truth to power. Iran’s environmentalists come to mind.

Yet, much of what we see today is disenchanted, disconnected, and fatally disinterested - the consequence of the State systematically stripping the people of any agency. If the leaders of the Islamic Republic think that ‘patriotism’ will come to their rescue, they should think again. Patriotism may yet blossom, but not in the current environment: as Taqizadeh noted all too astutely, it cannot flourish in the absence of freedom.

Professor Ali Ansari is a historian of Iran at the University of St Andrews.

This first appeared on Professor Ansari's Substack.

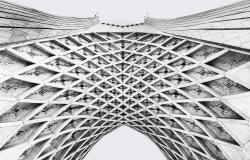

Photo by Hamid Mohammad Hossein Zadeh Ha

Notes

1 Orwell’s distinction while analytically useful, does not necessarily convey the ambiguity that exists in practice.

2 Hasan Taqizadeh Aghaz tamadon khareji (tasahol va tasmeh, azadi, vatan, mellat) (Acquiring Foreign Civilisation: political tolerance, freedom, patriotism, nation), Ramin, Tehran, 1379 / 2000, 73. The word used by Taqizadeh is ‘vatan-parasti’, literally ‘worship of the homeland’ but more akin in this context to patriotism rather than nationalism. I have nonetheless retained both words here.

3 Sir John Chardin, ‘A new and accurate description of Persia’ (1724), 127

4 A good early example, sadly often repeated, were members of student body who seized the US embassy in 1979, earnestly inquiring about visas to the United States from their recently released hostages.