The EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy and the challenge of competitiveness in the era of geo-politicized interdependence

Eugenia Baroncelli examines the EU’s new trade and industrial policy OSA concept, exploring the consequences of its recent ‘competitiveness’ upgrade. This is a chapter for a forthcoming e-book by the Global Governance Research Group of the UNA Europa network, entitled ‘The European Union in an Illiberal World’.

A long-time champion of economic openness, the European Union (EU or Union) has adapted to an increasingly geopoliticized world, reorienting its support for multilateral liberalization towards greater self-reliance. Drawing on the old notion of “strategic autonomy,” which has re-emerged in the debate on EU security since 2013, the EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy policy concept (OSA) has guided the redefinition of the EU’s trade policy in the 2020s (Commission 2021), embodying Brussels’s middle-of-the-road approach to achieving economic security and fostering technological sovereignty. OSA reasserts Brussels’ past commitments to multilateralism, qualifying them in the new global context. Filtered through internal dynamics, it regroups EU and Member States’ responses to external challenges from the international system.

This chapter examines the redefinition operated by the EU through the OSA policy concept, and its enhancement via the competitiveness discourse. While the EU “pendulum” has now oscillated towards autonomy, and away from openness, Brussels has in truth embarked on a path of “reluctant geopoliticization” (Herranz-Surallés et al. 2024). Except for select measures, the chapter argues, OSA mercantilism remains primarily reactive and defensive, with the Union’s calls to competitiveness serving as a rhetorical bridge to cement the consensus between its liberalizing and autonomist “souls”. Second, the chapter contends that the timing and shape of this change has been premised on the convergence of three main components: a Franco-German consensus (1); a compromise between the European Commission’s Directorate Generals (DGs) most pro-autonomy (DG GROW, DG CNECT, DG DIGIT) and the most hands-off, market-oriented DGs (DG TRADE, DG COMP, DG ECFIN) (2); and widespread support from citizens and the private sector (3). The chapter concludes by examining the potential of the “OSA-cum-Competitiveness EU model” to navigate the challenges of geopoliticized interdependence.

Rebalancing openness through strategic autonomy: the EU’s approach to defensive mercantilism

Early on, OSA substantiated Brussels’ defensive reaction to global, geopoliticized protectionism, particularly against allegedly unfair Chinese competition. Since 2018, new OSA tools have been introduced to catch up with “Trump I” measures and to mitigate the impact of the US-China trade war. During Covid-19 in 2020, and since the 2022 Ukraine War, OSA instruments have become the EU response to critical shortages. More recently, since the 2023 Gaza War and the 2025 “Trump II” trade shocks, OSA has been upgraded as the EU’s main strategy to ensure economic sovereignty vis-à-vis both friends and foes.

As the EU’s “adaptive response to a changing external power and ideological environment,” OSA also features “a panoply of policy instruments” not always compatible with WTO norms and regulations (Baroncelli and Ülgen 2024). Its origins are due to two opposing tendencies, that have co-existed in EU institutions: a neo-mercantilist protectionist soul, mostly endorsed by DG Internal Market (GROW) and by the EU Council, broadly, on the one hand, and a neo-liberal free-market soul, championed by DG Trade together with a consistent portion of the European Commission (EC), on the other (Gehrke 2022; Schmitz and Seidl 2023). The result is a peculiar mix of “postliberal welfare,” in response to calls for renewed embeddedness (i.e. state and EU regulation of markets), an EU tech-green industrial policy course, and a “strategic yet mainly defensive mercantilist approach to trade policy” (Baroncelli and Ülgen 2024).

OSA measures can be regrouped under two main rubrics: i) “new tools” supporting EU entrepreneurs in high-tech (EU Chips Act) and clean tech (CBAM – Carbon Border Adjustment Measure, CRMA – Critical Raw Materials Act, and NZIA – Net-Zero Industry Act), and ii) more “traditional” trade and industrial policy tools (the EU FDI-Screening Mechanism, FDI-SM, the New Export Control Regime, Foreign Subsidies Regulation or FSR, the Single Market Emergency Instrument -SMEI, and the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) with its associated Enforcement Regulation). Based on original research and recent literature on specific instruments (Baroncelli and Ülgen 2024), a typology of these OSA measures is given here, with two main dimensions: i) their innovative potential, relative to similar tools adopted by other countries; and ii) their defensive vs offensive propensity, relative to existing trade policy standards.

Albeit criticized by the BRICS as EU green protectionism, the CBAM has given Brussels world primacy in the adoption of a “polluter import fee” vis-à-vis both China and the US. An innovative “carbon border tax,” CBAM mandates carbon emissions notifications by exporters to the EU in 6 carbon-intensive sectors, leveling the playing field for EU producers. To date, Brussels’ leadership through CBAM has stimulated competitive approximation (by China), gradual adjustment (by the US, pre-Trump II), and several diplomatic openings towards joint schemes (Canada, UK, Türkiye).

Through selectively protectionist measures in trade and targeted investment for 17 critical raw materials (minimum targets for domestic extraction, processing and recycling), the CRMA appears by contrast to be a reactive EU move, to reduce dependency from China’s dominant position as a rare-earths supplier, and regain centrality in the design and fabrication segments vis-à-vis the US. Aiming to produce domestically at least 40% of the technology to reach carbon neutrality or “net-zero CO2 emissions” by 2030, the NZIA is also essentially a response to the pre-existing “green” US IRA (Inflation Reduction Act) components, and the established Chinese primacy in select clean tech segments. Followership is reflected also in the EU Chips Act, a digital tool with significant implications for decarbonization efforts, which aims to double the EU’s share in global semiconductor markets by 2030. In truth, however, the Chips Act replicates a reshoring akin to that pursued by the US Chips and Science Act (under the Trump I & II, and Biden Administrations). The EU Chips Act is substantially smaller in size (€43bn) compared to its foreign counterparts ($52bn without private funds envisaged by the US, the $150bn forecast by China until 2025, or the $450bn budgeted by South Korea from private funds until 2030, Baroncelli and Ülgen 2024).

The remaining OSA trade and industrial policy tools have a mostly defensive nature, with the potential exception of the ACI-cum-Enforcement Mechanism. Through its ambitious FDI-SM, Brussels has Europeanized the governance of FDI inflows, screening investments infringing national security and public order. While innovative, and potentially offensive on some counts (Bauerle Danzman and Meunier 2024), the FDI-SM originated from the EU’s will to reduce technology leakages from rising Chinese FDI, yet blocked only 3% of screened investments in 2022. In addition, fragmentation patterns have emerged between technologically advanced states (such as France, Germany and Italy) eager to reduce Chinese high tech FDI, and laggards (such as Greece, Cyprus and Portugal) benefitting from Chinese FDI inflows in mature sectors. The New Export Control Regime is similarly defensive, and has enhanced restriction on EU exports incorporating dual-use technologies aimed primarily at China and Russia. A necessary coordination mechanism on export controls in the critical area of semi-conductors, the Regime follows similar US pre-existing restrictions, and is essentially a catch-up response. Proudly labeled as a “state of emergency regulation for the 21st century” (Eller in Allenbach-Ammann 2022), the SMEI is a supply chain crisis management mechanism replicating similar domestic regulations (with the US Defense Production Act of 1950 as its main template). Mandatory stockpilings are also envisaged to deal with critical shortages/severe disruptions, and extended powers have been attributed to the Commission, with the Council deciding criticality levels using qualified majority voting (QMV). The SMEI is less ambitious than similar tools elsewhere, and its effectiveness has been questioned on grounds of high bureaucratic costs and lack of Commission’s expertise. The FSR in turn externalizes the EU acquis on state aid, extending the application of EU regulations on public subsidies to foreign entities directly or indirectly financing foreign companies operating in the EU and with EU firms, above specific turnover levels. A reactive move against distortionary subsidies from non-market economies, the FSR is in essence a competition policy tool addressed to foreign counterparts. While far-reaching, it is defensive in nature and has responded mainly to the US’ IRA. Critics have noted the burdensome reporting required by EU firms, casting doubt on the Commission’s expertise to review notifications.

Finally, defined by some as the EU “secret weapon” or “big bazooka” (Dyos 2025), the ACI-cum-EU Revised Trade Enforcement Regulation is a defensive tool, at the intersection between trade and security policy. It allows counter-measures by the EU in case of non-compliance by an alleged third-party infringer, pending a pro-EU adjudication by the WTO Appellate Body, yet it includes services and intellectual property rights (IPRs), that are currently not covered under WTO regulations. Infringement occurs under “economic coercion,” unilaterally defined by the Commission as “[a] situation where a third party attempts to pressure the EU or a MS into making a particular choice by applying or threatening to apply measures affecting trade or investment” interfering with the legitimate sovereign choices of the EU or a MS (EC 2024). Originally a reactive tool, ACI should protect Member States from future coercion, particularly following China’s economic targeting of Lithuania, when it welcomed the opening of a Taiwanese diplomatic mission in 2021. Relative to EU-US relations, the ACI is an insurance mechanism against the US’ excessive reliance on Sec.301 of 1974 US Trade Act (Trump I) and the shift to national security concerns under 1977 IEEPA (Trump II). Following the surge in the stop-go cycles of punitive tariffs threatened by Trump II in 2025, the EU has referred to ACI as a potential response tool (Politico 2025). As for any deterrence instrument, ACI’s effect is greatest when it is not used, entailing an escalation risk in case of pre-emptive or even preventive use under minimally frictional scenarios (Baroncelli and Ülgen 2024; Olsen and Schmuker 2024). The ACI has never been used to date, and rests on complex multi-stage procedures that require close coordination between the Commission and the Council, and last resort “dialogue” between the Commission and the party in question.

Overall OSA features a set of mercantilist yet mostly defensive tools, with the potential exception of ACI, if used to respond to minor frictions and in areas outside the WTO purview. Similarly, in green-high tech sectors, OSA indicates EU followership and catching up with other players, with the notable exception of the CBAM, which signaled potential innovative leadership by the EU, to advance an original and substantially progressive approach to greening trade and investment.

Competitiveness, industrial policy and trade protection

For some, the “open” qualifier in OSA most owes to the (liberal portions of the) Commission (Juncos and Vanhoonacker 2024). However, since the advent of the Second Von Der Leyen Commission, the 2025 Competitiveness Compass and Clean Industrial Deal have further qualified OSA, combining its defensive mercantilism with a more assertive industrial policy approach.

While the Commission has always been a vocal supporter of EU competitiveness, historically the EU’s industrial policy has been subordinated to the EU’s competition policy. The former falls in the remit of Council and Parliament mandates, and is regulated through EU and MS shared competence, with decisions taken through the co-decision procedure. The latter is based on exclusive EU competence and allows a greater margin of maneuver by the Commission over MS. Past EEC industrial policy responses to the 1980s neo-protectionist wave, and up until the mid-2010s, this subordination resulted largely in the EU’s preference for guaranteeing a level playing field (competition) among different national systems within the EU, instead of a more interventionist approach in support of EU (industrial) champions.

The global economic crisis of 2008, followed by the Eurozone crisis in 2011, however, prompted MS and EU institutions to rethink their responses to increasingly disruptive shocks. The Lisbon Treaty (2009) provided for EU-relevant industrial policy decisions to be taken via the co-decision procedure by the Parliament and the Council. Decisions are now adopted through Council QMV, and Council unanimity has been limited to select issue-areas and circumstances (taxation, state aid ex Article 107(3)(b) TFEU, specific cases of FDI screening and, specifically, strategic autonomy). Subsequently, transnational efforts by the Friends of Industry (FoI) group have advocated the need for the Union to “put industry at the heart of European decision-making”: the “China shock” (Autor et al 2013), Brexit (2016) and the unprecedented U-turn of the US during the first mandate of President Donald Trump put further pressure to redefine the EU trade and industrial policy approaches.

The emergence of a Franco-German consensus has been crucial in this process. While France has traditionally leaned towards autonomy and sovereignty, favoring internal (national, EU) support to growth and competitiveness, Germany has mostly championed openness and integration in world markets to enhance the competitiveness of domestic and EU industries. Overall, the game changer in this process has been Germany, which shifted towards tighter integration of the EU industrial policy when a row of Chinese acquisitions culminated in the takeover of Kuka, a major German robotics company in 2016 (Germann 2022, 3). Between 2016 and 2018, the major employer federations (BDI in Germany and MEDEF in France) aligned with French and German policymakers, backed moreover by public opinions (Di Carlo and Schmitz 2023, 2076-2077). Since January 2025, the second Trump administration has inaugurated a never-before-seen series of stop-and-go cycles of threatened political re-alignments, protectionism and escape routes through collusion offers. Coupled with existing and new geopolitical crises (wars in the Middle East, protracted war in Ukraine), these uncertainties have contributed to the emergence of an EU-wide consensus over pursuing more assertive trade and industrial policies, under the banner of competitiveness, with drastic simplification, targeted support to innovative EU partnerships and protection from unfair foreign competition at their cores, as indicated in the Draghi Report of 2024, the Competitiveness Compass (2025), and the Clean Industrial Deal (2025).

From the Green Deal to the Competitiveness Compass: the return of economic security

While often chosen to brand European industrial policy endeavors, the notion of competitiveness has featured prominently in the development community during the 2000s, reorienting the discourse about stimulating domestic productivity to facilitate the integration of emerging countries in world markets. Tributary to 500-plus years of history (Reinert 1995), (EU) competitiveness is at the crossroads of domestic (industrial) policy and foreign (trade) policy, and has been employed alternatively as a synonym for growth-productivity and/or as an equivalent of trade performance (revealed comparative advantage, market shares, Hughes 1993, 1). According to the OECD, a competitive system should be able to meet the test of foreign competition and improve domestic welfare at the same time: i.e. sell domestic products and services at a profit “under open market conditions” while also “maintaining and expanding [national] real income” (OECD 1992, 237; quoted in Reinert 1995, 25).

Compared to previous EU initiatives, the recent EU revamping of competitiveness seeks alternative paths to support internal productivity, while adapting to unprecedented levels of interdependence that are also weaponized along geopolitical divides. Such a mix puts multiple responsibilities on the EU and its MS. Outright openness is questioned, but market integration cannot be reversed altogether, if not at a very high cost for private and public agents. The resilience of EU citizens has also been tested severely since the 2008 crisis, with notable impacts on domestic political stability, and a shift away from centrist parties, in favor of extremism and Euroscepticism. OSA supply-side measures must now be balanced by EU support to concerned workers and consumers (far more numerous now compared to 2010s green-conscious voters and 'globalization losers'), to ensure cohesion through redistribution to disadvantaged groups and MS. As Western democracies are facing a political “solvency gap” with their constituencies (Trubowitz and Burgoon 2023), in an era of geopoliticized interdependence, the EU and MS are simultaneously struggling to reconcile the domestic social protection built up during the long postwar boom (1950s-1970s) with a liberal, internationalist foreign policy approach, which now seems both anachronistic and counterproductive.

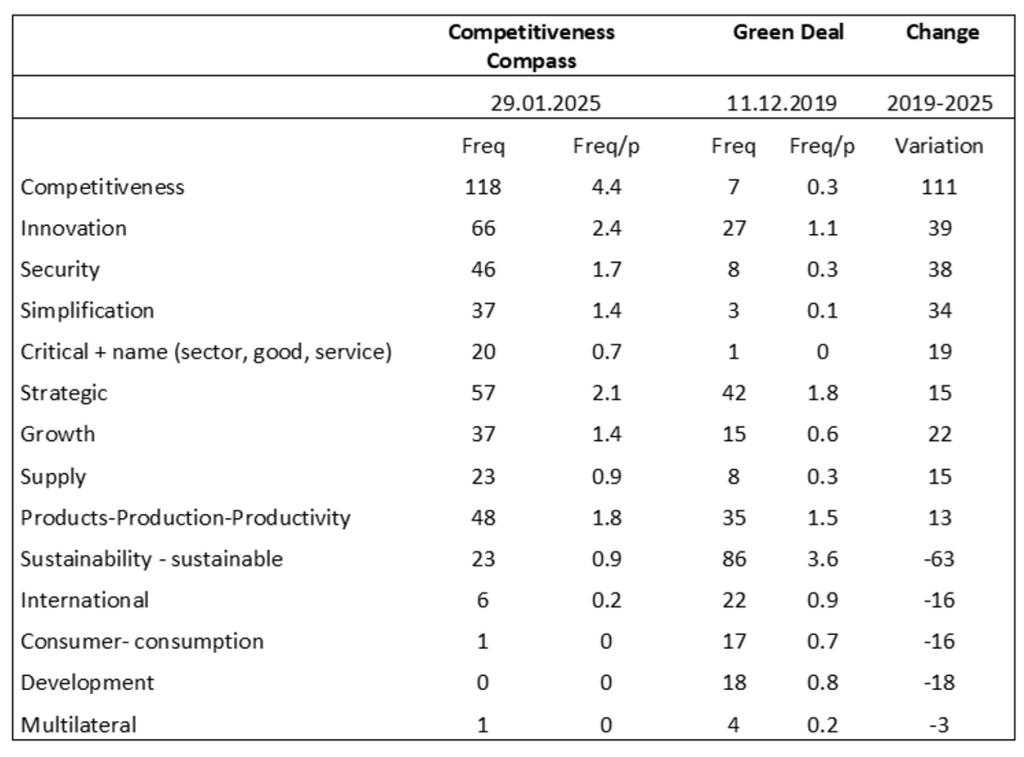

In the mid-2020s, Brussels trade and industrial responses are prioritizing competitive, rather than cooperative approaches, emphasizing innovative growth, productivity and secure supplies, to strengthen the EU’s internal cohesion vis-à-vis external counterparts. A comparison between the EU Green Deal (2019) and the EU Competitiveness Compass (2025) reveals a major shift in wording and use of concepts.[1] This prima facie evidence is based on arguably the “greenest” among the EU recent endeavors, on the one hand, and the most supply-targeted of Brussels’ responses to the 2025 global downturn, on the other hand, so caution and contextualization are advised. The Competitiveness Compass, however, also substantiates Brussels’ most recent attempt at shortening the gap between its domestic and foreign economic policies through the concept of competitiveness, to facilitate the green transition and competitive re-shoring. While in its 2019 blueprint for a green deal the Commission mentioned competitiveness a mere 7 times (in a text of 24 pages), the new Compass includes 118 mentions (in a 27-page text). Innovation (66) and security (46) are the next most referred-to concepts, compared to the 2019 Green Deal. Other semantic areas have experienced a clear resurgence in use, particularly those gravitating around the supply side of the economic cycle (compared to consumption), growth, and simplification (see Table 1).

Table 1. From Sustainability to Competitiveness: Comparing the Commission’s word choice and frequencies in the EU Green Deal and Competitiveness Compass

Author’s calculations based on EC (2019) and (2025). Word frequencies (Freq) and frequencies per page (Freq/p) refer to each term and composite signifiers, see Note 1.

References to multilateralism are virtually non-existent in the 2025 Compass, which mentions “multilateral partnerships” once, and includes “cooperation” only with respect to intra-EU deals, while the Green Deal called for “multilateral cooperation” and cooperation with external partners at several junctures. The Compass mentions “development” only with reference to EU-specific projects, and never qualifies it as “sustainable” or puts it in the context of multilateral endeavors. This is revealing: while the EU has been among the most vocal and resilient supporters of the UN Agenda 2030 and SDGs through the adoption of its Green Deal, the tone of the 2025 Compass indicates a clear semantic detour from that previous course. Calls for protection recur in both Commission’s Communications, yet with very different meanings. While the 19 mentions of protection in the Green Deal refer to citizens’ protection and nature conservation, the 14 mentions in the Competitiveness Compass are relative to trade, industrial and labor protection. True, the Compass contains numerous references to workers’ rights and social protection, yet the dimension is primarily social and economic, not environmental.

The 2025 Compass shows that Brussels’ response to the current geopolitical tensions lies mainly in economic fixes, immediately targeted at supply, yet also close to the needs of workers. The notion of sustainability is now being filtered through an EU lens (what is feasible within the Union), as opposed to a global one (an inter-generational compact under the aegis of the UN), and prioritizes socio-economic objectives over environmental concerns.

Conclusion

In the new global context, dense economic ties coexist with market segmentation along geopoliticized lines. As an incremental compromise between the different “souls” of the EU, OSA has been Brussels’ response to this peculiar mix. As argued here, catch-up measures and defensive mercantilism have mostly informed both green-high tech and traditional trade-industrial policy OSA measures. Two notable exceptions stand out – the CBAM and the ACI-cum-Trade Enforcement Mechanism – which reveal the potential for the EU’s incipient leadership in greening trade regulations, and in setting deterrence standards, with potential offensive implications, in the face of economic coercion.

Situated at the intersection between industrial and trade policy, competitiveness features prominently in the new EU economic policy agenda, and serves as a conceptual bridge between both the OSA autonomy-openness balance, and the consumer-supplier divide within Member States’ electorates. Such rebalancing in favor of EU productivity and innovation also includes redistribution, to ensure cohesion among MS and citizens, that have remained at the center of the second von der Leyen Commission’s economic strategy. Multilateralism and global environmental sustainability are the envelopes that stand to lose the most from this new course. While ensuring against both allies and adversaries, the new competitiveness course risks impairing the EU’s potential to become a global leader in green and clean technologies. In light of the “dirty growth” policy course endorsed by the US under the second Trump administration, such missed opportunities appear further disappointing, as China would become the only pole of attraction for emerging market countries in implementing the clean industrial transition. In other words, if the EU’s recipe for competitiveness compresses the green envelope too much for the sake of industrial productivity, the consequences will reduce the EU’s very ability to negotiate meaningful partnerships with countries outside the transatlantic compact.

Eugenia Baroncelli is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political and Social Sciences, University of Bologna. Email: eugenia.baroncelli@unibo.it

Photo by Wolfgang Weiser

Notes

1. Additional details on word frequency and collocation text analyses performed for this chapter are not reported here due to space constraints, but are available upon request.

References

Allenbach-Amman, János. 2022. “SMEI: The many pitfalls of the EU’s new supply chain control tool.” Euractiv 20.09.2022

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. "The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States." American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68.

Baroncelli, Eugenia and Sinan Ülgen. 2024. “Open Strategic Autonomy and the Future of the Global Economic Order,” in Balfour, Rosa and Sinan Ülgen (eds) 2024. Geopolitics and Economic Statecraft in the European Union. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Brussels: Carnegie Europe, 29-50. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/11/geopolitics-and-economic-statecraft-in-the-european-union?lang=en#eu-open-strategic-autonomy-and-the-future-of-the-global-economic-order

Bauerle Danzman, Sarah and Sophie Meunier. 2024. “The Geoeconomic Turn of the Single European Market: From Policy Laggard to Institutional Innovator.” Journal of Common Market Studies 64 (4): 1097-1115. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13599

Di Carlo, Donato and Luuk Schmitz. 2023. “Europe first? The rise of EU industrial policy promoting and protecting the single market” Journal of European Public Policy, 30 (10): 2063–2096. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2202684

Dyos, Stuart. 2025. “Europe’s secret ‘big bazooka’ could be a key retaliatory tool against Trump’s new tariffs.” Fortune, 03.04.2025. https://fortune.com/2025/04/03/european-union-ursula-von-der-leyen-europe-tariffs-imports-exports-big-bazooka-vitale-ing-president-donald-trump/

European Commission. 2019. “The European Green Deal - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions”, Brussels, 11.12.2019 COM(2019) 640 final

European Commission. 2021. “Trade Policy Review – An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy,” Brussels, 18.02.2021 COM (2021) 66 final

European Commission. 2024. “Anti-Coercion Instrument.” EC webpage: https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/anti-coercion-instrument

European Commission. 2025. “A Competitiveness Compass for the EU, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions” Brussels, 29.1.2025 COM(2025) 30 final

Gehrke, Tobias. 2022. “EU Open Strategic Autonomy and the Trappings of Geoeconomics.” European Foreign Affairs Review, 27(SI): 61-78.

Germann, Julian. 2022. “Global rivalries, corporate interests and Germany’s “National Industrial Strategy 2030.” Review of International Political Economy, 30(5): 1749–1775. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2130958

Herranz-Surrallés, Anna, Chad Damro and Sandra Eckert. 2024. “The Geoeconomic Turn of the Single European Market? Conceptual Challenges and Empirical Trends.” Journal of Common Market Studies 62(4): 919-937. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13591

Hughes, Kirsty. 1993. European Competitiveness. Cambridge Mass: Cambridge University Press.

Juncos, Ana and Sophie Vanhoonacker. 2024. “The Ideational Power of Strategic Autonomy in EU Security and External Economic Policies.” Journal of Common Market Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13597

Olsen, Kim and Claudia Schmuker. 2024. “The EU’s New Anti-Coercion Instrument Will Be a Success if It Isn’t Used”. Internationale Politik Quarterly. 1/2024, 01.10.2024, https://ip-quarterly.com/en/eus-new-anti-coercion-instrument-will-be-success-if-it-isnt-used

Politico. 2025. “What’s in von der Leyen’s plan to save the EU economy?.” 30.01.2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/wheres-the-eu-competitiveness-compass-pointing/

Reinert, Erik. 1995. “Competitiveness and its Predecessors – a 500-years cross-national perspective.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics. 6(1): 23-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0954-349X(94)00002-Q

Schmitz, Luuk and Timo Seidl. 2023. "As Open as Possible, as Autonomous as Necessary: Understanding the Rise of Open Strategic Autonomy in EU Trade Policy.” Journal of Common Market Studies. 61(3), 834-852.

Trubowitz, Peter and Brian Burgoon. 2023. Geopolitics and Democracy. The Western Liberal Order from Foundation to Fracture. Oxford University Press: New York.