Reviving Trade Alliances: The Geopolitical and Economic Significance of the EU-Mercosur Agreement

Maria C. Latorre and David Suárez-Cuesta examine the benefits of the EU-Mercosur Agreement for both parties, noting it also encourages activities with lower CO2 emissions. The text is part of a forthcoming e-book by the Global Governance Research Group of the UNA Europa network, entitled ‘The European Union in an Illiberal World’.

Introduction: setting the stage of the EU-Mercosur Agreement

In today’s uncertain international landscape, ensuring good trade relations becomes even more necessary. The European Union (EU) presents itself to the world as a reliable and predictable partner. In this context, the EU-Mercosur Agreement is once again on the table. What is the economic impact of the Agreement? Are there risks for the Spanish and European economies? What do economic estimates dictate in light of environmental concerns and the interests of Europe’s farmers?

The EU-Mercosur Agreement has an important strategic and economic potential within the global economy for several reasons. First, current barriers, especially tariffs in the Mercosur countries (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay), are so high that their reduction would significantly boost trade relations. Second, the Agreement creates a relationship that goes far beyond tariffs and other trade regulations in a vast region. In this sense, it follows the path of EU agreements that cover many areas beyond trade. Finally, the Agreement provides geopolitical advantages through which the EU can strengthen its political and cultural ties in the region.

In this paper we offer an analysis of a controversial agreement. We delve into the uniqueness of this trade agreement and present its key effects for all signatories, as well as for the global economy. Our ex-ante estimates are primarily based on a Computable General Equilibrium Model (CGE). Our multi-sector, multi-factor and multi-region CGE model of the global economy (Latorre, Yonezawa, and Olekseyuk, 2021) extends previous models (Latorre and Yonezawa, 2018; Latorre, Olekseyuk, and Yonezawa, 2019, 2020). In particular, it extends the work of Balistreri, Hillberry, and Rutherford (2011), which pioneered the incorporation of Melitz's (2003) model into a CGE model. Our model thus incorporates Melitz's (2003) effects on exporters' productivity. We also add the presence of multinational firms operating in monopolistic competition following Krugman (1980), and the environmental effects on the global economy. Furthermore, we explain why other models fail to quantify certain aspects of this agreement, undervaluing its positive effects. Our simulations are derived from the texts negotiated under the agreement, which we have carefully analysed.

The results provide evidence that counter several popular misconceptions, such the view that this is a "cows for cars" agreement, which raises environmental hazards, or that it will lead to a flood of agricultural products from Mercosur, that will be harmful to European farmers.

The uniqueness of the EU-Mercosur Agreement

On 6 December 2024, the European Union (EU) and the four founding members of Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay) reached a new political agreement. Although the EU already has numerous trade agreements with Latin America, this one stands out for its scale, as the four Mercosur countries constitute the world's fifth-largest economy and account for a population of more than 270 million. As China continues to increase its influence in the region, the EU will be the first major trading partner to formalize an agreement with Mercosur, which neither the US nor China have, granting preferential access to EU countries.

The agreement provides transparency and avoids the opaque import and export licensing procedures that underlie the significant costs and barriers for companies trading with the Mercosur countries. Considering only tariff reductions, the agreement represents a saving of approximately €3.6 billion for European companies, a sum that is four times more than the gains for EU industry under the EU-Japan Free Trade Agreement (JEFTA) and six times more than those obtained from the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with Canada (CETA) (Ghiotto and Echaide, 2020, p. 22).

Evaluating the economic outcomes of the Agreement

Our model (Latorre, Yonezawa, and Olekseyuk, 2020) extends, as already mentioned, the innovative work of Balistreri, Hillberry, and Rutherford (2011). We also include the presence of multinationals in the service sectors in a climate of monopolistic competition following Krugman (1980). This methodology allows us to offer a wide range of results at both the macro and microeconomic levels, derived within the coherent and robust framework of a single general equilibrium model.

For the modelling we have introduced further extensions by incorporating the presence of unemployment (following previous work by Latorre, Yonezawa, and Zhou, 2018), as well as frictions in labour mobility. Regarding the analysis of environmental sustainability, we offer quantitative results of the impact of the treaty on CO2 emissions, calculated endogenously, responding to fossil fuel consumption linked to the production of different sectors and to private consumption. To quantify them, we consider the detail offered by the model's input-output framework.

The CGE model disaggregates the global economy for the regions of Spain, the Rest of the EU (EU26), Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and the Rest of the World. We model the impact of four important elements of the agreement: 1) tariffs and quotas; 2) non-tariff trade measures; 3) non-tariff measures on foreign direct investment (FDI) in services; and 4) public procurement.

The original goods trade data from the GTAP database (Aguiar et al., 2019) have been replaced by the average trade between Spain and the EU-26 and the four Mercosur countries for the period 2017-2019, based on data from the International Trade Centre (2020a). Furthermore, the Most Favoured Nation tariffs are also based on the latest available year, 2019 (International Trade Centre, 2020b): these tariff rates take into account, among other aspects, Paraguay's withdrawal from the Generalized Scheme of Preferences. Additionally, our simulations incorporate negotiated quota and tariff reductions as listed in Annex 1 of the Trade in Goods chapter of the Agreement. A total of 9,132 8-digit Combined Nomenclature (CN) codes have been added to 31 goods sectors in our model on the European Union side, while 9,933 8-digit “Nomenclatura Común del Mercosur” (NCM) codes have been converted to the same sectors on the Mercosur side.

The modelling of multinationals focuses on the service sectors because it is in these sectors where the mode of provision of foreign goods via multinationals (Mode 3 of service provision) is especially important. Data on the weight of multinationals in the different sectors come from Eurostat (2019), TISMOS (WTO, 2020), and the Financial Times (2020) “fDiMarkets.” Our simulations of openness to the provision of services through exports or FDI, as well as those of public procurement, are based on the chapters and annexes of the negotiated agreement, which reflect, for example, which sectors are liberalized and which are not, and contain indications on the degree of liberalization ambition.

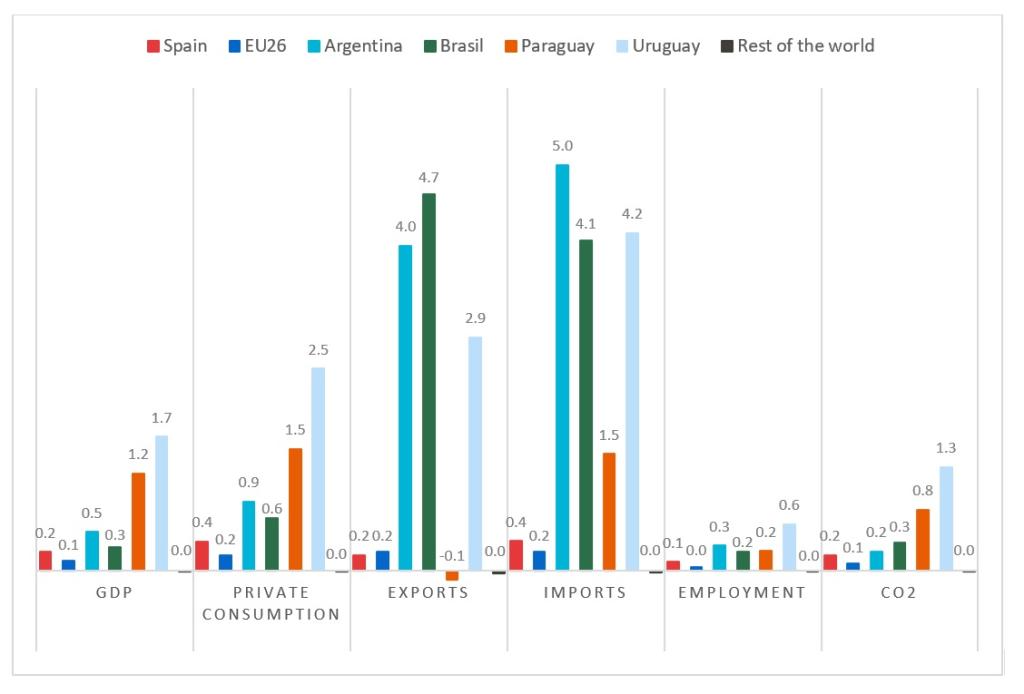

Figure 1 shows the impact of the EU-Mercosur agreement on the main macroeconomic variables in Spain, the rest of the EU (the EU26, i.e. EU27 without Spain), Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and the rest of the world, once all the components of the agreement that we quantify in this paper have been implemented. Specifically, the variables we present are GDP, private consumption (change in equivalent consumption), aggregate exports and imports, employment and CO2 emissions.

Figure 1. Impact of the EU-Mercosur Agreement on Key Macroeconomic Variables by Region/Country at the End of the Implementation Period (% Change from Initial Levels)

Source: Latorre, Yonezawa y Olekseyuk (2021)

The estimated impact would be that identified for the year 16 (i.e. fifteen years after the agreement comes into force), when the agreed tariff liberalisation process will be completed and the tariff regime for the future will therefore be fixed. Figure 1 shows that the gains for Spain are significant and greater than for the rest of the EU. However, the Mercosur countries should benefit most from the Agreement when compared to the EU as a whole. The increases recorded are produced solely by the forces that the EU-Mercosur agreement would set in motion, ceteris paribus. In the real world, the agreement will interact with many other factors, such as the impact of other fiscal, monetary and trade policies, etc., which could push GDP and other variables in the regions towards growth or contraction.

In the long term, the agreement will have a positive impact on the economic well-being of both the EU (and Spain in particular) and the Mercosur countries. This impact is reflected in increases in GDP, private consumption and employment, as well as in trade. All the macroeconomic variables in Figure 1 show an upward trend for the signatories to the agreement.

At the same time, the EU-Mercosur agreement has sparked debate about its potential environmental impact. However, in Mercosur, Spain and EU26, the treaty generates efficiency in terms of CO2 emissions. In other words, the economic growth driven by the agreement is less CO2-intensive than before the agreement.

Climate policies, at least in the EU, are imposing serious obligations that affect production and consumption patterns. In our estimates, we do not analyse the effects of these climate policies. What we have estimated is the initial distribution of CO2 emissions among different regions and sectors, as well as the regional and sectoral contribution to the emissions generated by the agreement. By year 16, the agreement generates a small increase (0.14%) in CO2 emissions from the EU-Mercosur region, while the GDP of the EU-Mercosur region increases by 0.17%. The same is true for the global economy, whose GDP increases by 0.03% with the agreement, with emissions increasing by 0.01%.

This is largely due to the fact that, as shown in Figure 1, economic activity should shift from the Rest of the World as a whole to the EU-Mercosur region. As the Rest of the World is much more emissions-intensive than the EU-Mercosur region, there is a slight improvement in the global emissions/GDP ratio for the world. As expected, given its higher GDP, the European part of the agreement contributes most to the emissions resulting from it in the EU-Mercosur region. The combined contributions of Spain and the EU account for 59.92% of the increase in total emissions within the EU-Mercosur region, while Brazil and the rest of the Mercosur countries represent respectively 29.41% and 11.07% of the emissions increase. Most of the extra emissions (50.09%) come from service sectors, particularly electricity and transport, whereas agriculture only represents 3.97% of the growth in emissions generated by the agreement, and manufacturing 14.12%. The remainder of the new emissions (to make up 100%), corresponds to private consumption (31.81%), which is the second most significant source of emissions in Spain and the rest of the EU. Thus, 31.81% of the increase in emissions under the agreement (compared to 2016 levels) is explained by private consumption, mainly due to demand for fossil fuels for cars by citizens of the EU-Mercosur region, as well as for gas used in heating and cooking.

These results should not be overlooked because the alarm about sustainability focuses on agriculture and, in particular, beef. It is true that we have not included other greenhouse gases (like methane from cattle) in our analysis, and these are particularly significant in the agricultural sector. However, our analysis shows that, in terms of CO2 emissions, the sectors that need to be targeted are mainly transport and electricity, as well as the fuels we use in our cars.

To explore this point further, we have also analysed total EU imports, i.e. combined imports for the EU26 and Spain, in the 16th year of the agreement. Most of Mercosur's contribution to EU imports is concentrated in manufacturing, which represents 59.62% of total imports from Mercosur. This is followed by services (25.42%), which considerably exceed agricultural products (14.96%). The livestock sector in our model is broader than beef, as it includes cattle, sheep, goats and other livestock, as well as their corresponding manufacturing products. This sector would represent around 3.75% of EU imports from Mercosur in year 16.

In 2016, more than half of the EU imports in this sector (67.41%) came from within the EU itself. Mercosur represented 12.66% of total imports in 2016, of which, 4.55% came from Brazil and the highest percentage, 8.12%, from the other members (4.84% from Argentina, 0.36% from Paraguay, and 2.92% from Uruguay, totalling 8.12%). Looking at total exports from the Mercosur region to the EU (still considering Spain and the EU26 together), most exports in the livestock sector represent 6.97% of total exports in Argentina, 1.87% in Brazil, 4.55% in Paraguay and 17.28% in Uruguay. Therefore, we can largely dismiss the risk to the Amazon, given the low level of beef production in Brazil. Furthermore, the type of beef demanded by Europeans comes from other areas of Brazil, and not the Amazon, as it is not beef raised in tropical areas.

Other parts of the food sector dominate total contributions (11.80%) of Mercosur exports to the EU. But these are closely followed by another sector that may come as a surprise, namely business services, which represented 11.43% of total EU imports from Mercosur in 2016. In fact, business services represent a significant share of Mercosur’s exports, not only from Brazil (11.80%) and Argentina (11.33%), but also from Paraguay (6.83%) and Uruguay (8.72%): these figures corresponding to the total exports of each Mercosur member to the EU.

The Agreement will favour employment and wages in agricultural sectors such as olive oil, dairy products and wine in the EU. In the latter two, production is also expected to increase. On the other hand, crops such as fruit and sectors such as pork and beef could experience moderate declines in production, with beef being the most affected, with an estimated reduction of 1% in Spain and 1.2% in the rest of the EU.

To protect European livestock farming, the agreement defines a maximum limit for imports of beef and poultry from Mercosur of 1.6% and 1.4% of EU consumption levels. This means that once this limit is reached, any additional imports will remain subject to the current high tariffs and restrictions, thus preventing any significant deviation from the current situation. In addition, the agreement includes mechanisms allowing the EU to temporarily suspend tariff preferences if an increase in imports causes or threatens to cause serious damage to European agricultural producers.

Conclusions

The EU-Mercosur Agreement has taken on an important role given the current geopolitical instability. In international trade, it is therefore even more important to have reliable allies. In this sense, the EU represents one of the largest markets and one with the greatest regulatory stability worldwide.

Our results show that both regions will benefit from the Agreement, although it is the Mercosur countries that should experience the greatest gains. While the European Union has numerous trade agreements in Central and South America, this agreement is, in terms of population and tariff savings, the largest that both regions have signed to date.

Thanks to this agreement, both regions "win". All parties benefit, but the positive impact will be most visible in Latin America. Although agricultural exports hold out positive prospects for the Mercosur countries, the gains will be much greater for exports of manufactured goods and some services. It is estimated that beef, for example, will account for around 3.75% of Mercosur imports by the EU, while in the case of manufacturing and services, once the agreement is implemented, these sectors should account for 59.6% and 25.4%, respectively. Although the beef sector generates considerable debate, it is only one of many agricultural activities. However, the total emissions generated by the agricultural sector (as a whole) linked to the EU-Mercosur Agreement do not exceed 3.75% of the total extra emission due to the Agreement. Although this study does not include emissions of gases other than CO2 (such as methane from livestock) our results indicate that the treaty encourages greater activity in sectors that are less intensive in CO2 emissions, in addition to having a positive impact on growth and employment.

Maria C. Latorre is a Full Professor of Applied Economics at Universidad Complutense. She was selected as a Seconded National Expert to the European Commission (Chief Economist Unit, DG Trade, Brussels) and has been a member of its Expert Group on International Trade since 2016. She is Co-Chair of the research groups on Data Science and Global Governance, both from the Real Colegio Complutense at Harvard University, where she is also a Research Fellow. She co-leads the “Una Europa Global Governance Research Group”, together with Prof. Jan Wouters from KU Leuven.

David Suárez-Cuesta is a faculty member in the Department of Economic Analysis and Quantitative Economics at Universidad Complutense of Madrid. His current research focuses on the impact analysis of infrastructure investment using CGE models. He is the project operations manager of the Global Governance Research Group and a member of the Study Group in Data Science at the RCC at Harvard University.

Photo by Beate Vogl

References

Aguiar, A, Chepeliev, M., Corong, E., McDougall, R. & Van Der Mensbrugghe, D. (2019). The GTAP Data Base: Version 10. Journal of Global Economic Analysis, Vol. 4 (1), pp. 1-27.

Balistreri, E.J., Hillberry, R.H. & Rutherford, T.F. (2011). Structural estimation and solution of international trade models with heterogeneous firms. Journal of International Economics, vol. 83, pp. 95-108.

Eurostat (2019). Inward fats. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

Financial Times (2020). fDi Markets. Available from: https://www.ft.com/capital-markets

Ghiotto, L., & Echaide, J. (2020). El acuerdo entre el Mercosur y la Unión Europea: Estudio integral de sus cláusulas y efectos. CLACSO. Available from: https://www.clacso.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Informe_Mercosur_UE_2020.pdf

International Trade Centre (2020a). Market Access Map. Available from: https://www.macmap.org/

International Trade Centre (2020b). Trade Map. Available from: https://www.trademap.org

Krugman, P. (1980). Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. American Economic Review, vol. 70, pp. 950-959.

Latorre, M. C., Yonezawa, H., & Zhou, J. (2018). A general equilibrium analysis of FDI growth in Chinese services sectors. China Economic Review, 47, 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.09.002

Latorre, M. C., & Yonezawa, H. (2018). Stopped TTIP? Its potential impact on the world and the role of neglected FDI. Economic Modelling, vol. 71, pp. 99-120.

Latorre, M. C., Yonezawa, H., & Olekseyuk, Z. (2021). El impacto económico del Acuerdo UE-Mercosur en España. Secretaría de Estado de Comercio, Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo. Available from: https://comercio.gob.es/es-es/publicaciones-estadisticas/paginas/impacto-economico-acuerdo-ue-mercosur.aspx

Latorre, M. C., Olekseyuk, Z., & Yonezawa, H. (2020). Foreign multinationals in services sectors: A general equilibrium analysis of Brexit. World Economy, 43, 2830–2859. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/twec.13034

Latorre, M. C., Yonezawa, H., & Olekseyuk, Z. (2019). Trade and foreign direct investment-related impacts of Brexit. World Economy, 43, 2–32. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/twec.12859

Melitz, M.J. (2003). The Impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, vol. 71, pp. 1695–1725.

World Trade Organization (2020). Trade in Services data by mode of supply (TISMOS). Available from: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/trade_datasets_e.htm